It’s Scotland’s oldest and original lending facility, created in 1680 before union with England. Andrew Welsh visits the

Library of Innerpeffray.

It could so easily have been one historic Courier Country landmark in acclaimed author Germaine Greer’s thoughts when she wrote of libraries as “reservoirs of strength, grace and wit; reminders of order, calm and continuity; lakes of mental energy neither warm nor cold, light nor dark”.

That description can confidently be applied to Scotland’s oldest and original lending facility, the Library of Innerpeffray, which was created in 1680 at a time when Scotland was still 27 years away from forging its union with England, while in France “the Sun King” Louis XIV was midway through his epic 72-year reign.

Unobtrusively tucked away in leafy surrounds close to the River Earn four miles south-east of Crieff, the library started life in the attic of tiny Innerpeffray’s St Mary’s Chapel, where it housed local laird David Drummond’s precious books collection.

Following his death, its running fell to the Innerpeffray Mortification charity, whose governors proudly unveiled Scotland’s first public lending library in 1694, along with a new rural school.

It was just as the Scottish Enlightenment was taking shape in 1739 that subsequent estate owner Revd Robert Hay Drummond – a future Archbishop of York – commissioned the architect Charles Freebairn to construct the Georgian reading room that still stands today, so that it could hold both the chapel’s contents and his own former book collection.

For more than two centuries residents of Crieff and nearby villages would walk the Strathearn countryside – including a wade across the river at one of its shallowest points – in order to gain knowledge about such things as theology, geography, astronomy, history and the sciences.

When the number of borrowers fell away post-war, the archive’s trustees eventually decided to cease lending in 1968, with the holder of Innerpeffray’s full-time librarian post – its grandly-titled Keeper of the Books has been a permanent feature since 1696 – devoting more time to the preservation of an increasingly fragile and valuable resource.

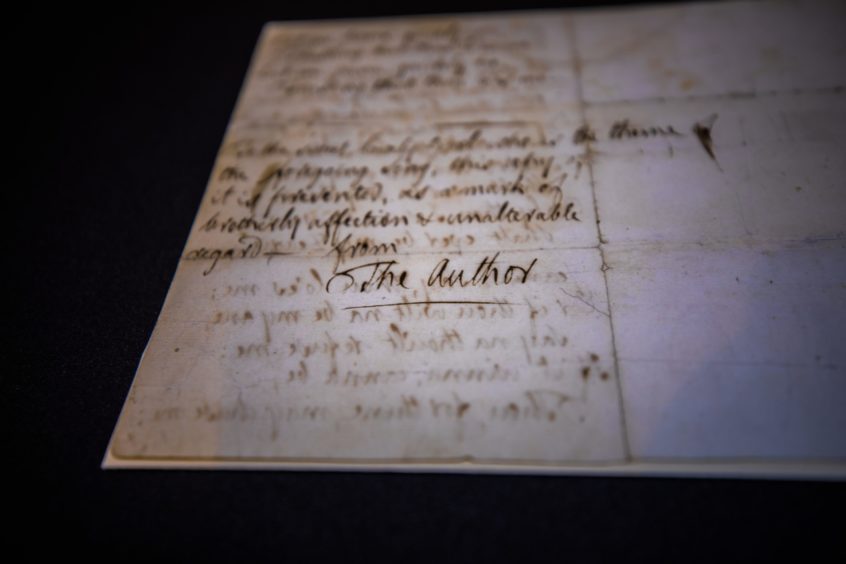

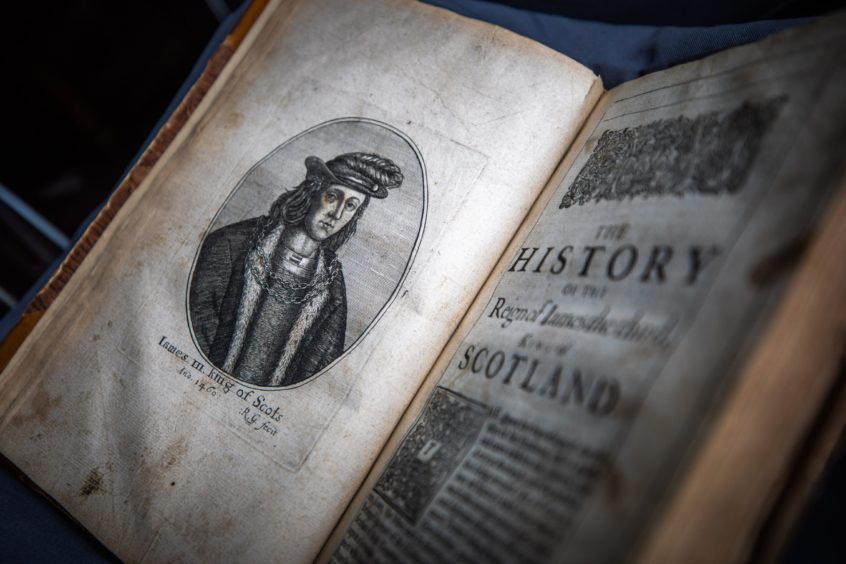

Boasting such treasures as a 1476 edition of the works of theologian John Duns Scotus – Innerpeffray’s oldest book – plus first editions by Enlightenment philosopher David Hume and literary giants Samuel Johnson and Robert Louis Stevenson, as well as lyrics handwritten by Robert Burns, the library has evolved into a fascinating visitor attraction in recent decades. It reopened with restrictions last month following four months of pandemic-enforced closure.

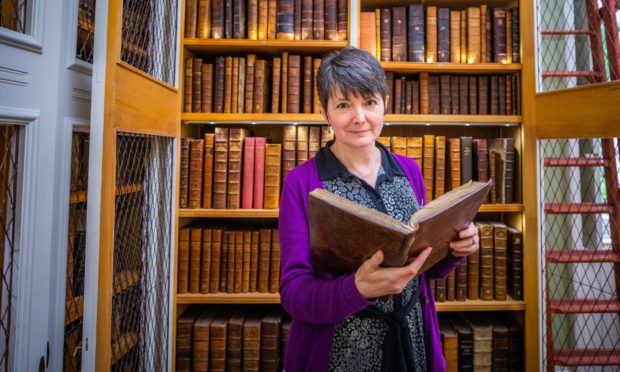

The 33rd incumbent in the Keeper role is Lanarkshire-raised Lara Haggerty, who first visited Innerpeffray and its 5,000 books, including a comprehensive borrowers’ register dating back to 1747, shortly after moving to Crieff in 2005.

Missing out on both a huge chunk of this year’s tourist season and a regular diet of fundraising social events has created inevitable challenges for one of the nation’s most niche attractions, but fortunately Lara was still able to work on her marketing duties while her 15-strong team of library volunteers locked down at home.

“It’s been very interesting for us to find out new ways of connecting with the people that know and love the library, and of finding new people,” she tells me. “We’ve been doing that through a series of filmed tours and we put out an appeal which was very generously supported. Our trustees were concerned at the start of lockdown but they’re now feeling that the library is going to be OK.”

Innerpeffray opened a new heritage trail for visitors to its tranquil grounds last year following a £100,000 fundraising campaign. Providing views of surviving Roman roads, the Earn-side walk tells the site’s story from the Ice Age to the present through a series of interpretive markers that’ve earned the library a nomination in this year’s Scottish Design Awards – and further work is imminent. “Most of the expense went on clearing the ground to get it ready,” says Lara.

“That cost more than I thought would’ve been possible but of course it’s highly skilled work. We needed to have trees cut down and have paths that are safe, so I’m sure we’ll look back on it in years to come and think that it was a great investment. It felt like a lot of money at the time but we hope that it’ll be here for a very long time to come, at least 25 years if not forever.

“We’d just completed that big project and were settling back to business as usual when it became not as usual.

“Fortunately we were able to tap into the support grants that were made available to Perth and Kinross Council very early on and that bought us a lot of time.”

Although plans for major summer celebrations to mark Innerpeffray’s 340th anniversary were axed months ago, visitors and locals still managed to enjoy spending time in its grounds while the library was being readied for reopening. Indoor tours are back up and running with capacity reduced to just two people alongside other Covid-related measures including dividing screens, hence the venue’s annual visitor tally is expected to be only around a tenth of its usual 2,000.

The library, which closes to the public over winter, holds regular exhibitions based around its rare books and the subject matter of the latest certainly resonates in the current climate. “We had a plague and pestilence exhibition a few years ago and when we were looking at reopening one of the volunteers suggested, almost as a throwaway, that we should stage it again,” explains Lara.

“I agreed, so we looked out some of the books and I think the display is amusing people, which is always good. We’ve got historical accounts of the plague happening in different cities over the world in a variety of books, magazines and journals, including the Scots Magazine.

“They can also see medical books with possible cures – we should perhaps say, ‘Don’t try this at home’ – and we’ve got a book of prayers which are said in time of plague, so there are words of comfort.

“It would take a medical expert to go through the books and find out whether or not there are any useful tips within them, however they can certainly give us hope. The fact is people do recover from plagues – it’s happened before and we’ve come out the other side of it.”

History is all around at Innerpeffray. The vast majority of the library’s titles are pre-19th Century and it’s clear there are plenty of relevant lessons from the past on its shelves. Lara affectionately refers to the hallowed venue as “a living library” and if you’re lucky, you might get the chance to hold Innerpeffray’s oldest book in your hands, and get a sense of the past almost coming to life.

So when the Keeper declares that back in the 15th Century its Duns Scotus “was really hot off the press, you could say”, you can understand why. After all, his treatise on theological doctrine was printed in Venice only around 17 years after the arrival of typographic art in the former Adriatic republic, a development that firmly established the publishing industry outside Germany where it’s widely recognised as having its European origins.

Being able to touch the library’s ancient tomes is a joy coronavirus took away, and Lara admits to feeling sad that there remains obvious need for caution. “The thing that’s special about Innerpeffray is that opportunity to hold the books for yourself and to feel them,” she adds.

“You can feel the temperature of the paper and the way that the leather feels in your hand, and missing that is terrible but we’re doing what we can. We are able to quarantine books ourselves if somebody makes a special request.

“I had a seven-year-old a couple of weeks ago who was very engaged with the visit and was admiring the really big books. So we got one of them off the shelf and let him hold it to see how heavy it was, and he was really taken with the fact that it was such a big old book.

“All we did then was we put that book into a safe space and we left it there for three days and then it went back on the shelf. So that worked, but we can’t bring lots and lots of books out in the way that we used to do.”

Listening to Lara speak with such obvious passion about her calling’s importance to learning brings to mind Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Archibald MacLeish’s wartime observation that librarians are more than mere custodians of print and paper, they are also keepers of the records of the human spirit itself.

Ask her how she feels about modern libraries storing a fraction of the number of books contained within Innerpeffray’s Category A-listed walls and Lara pauses for a moment. “There will always be a place for libraries,” she cautiously ventures.

“They are purveyors of information, and although the information in Innerpeffray’s time came from printed books, before that they were handwritten and today a lot of them are digital, and libraries have to respond to that. They have to be what their community needs.

“I’m definitely not against libraries embracing different technologies but I am against closing libraries. I think they’re very important places in our communities. I’ve heard some fabulous stories over the lockdown period about the ways libraries have been able to stay in contact with the people who need them as a means of communication socially and of occupying time.

“Librarians have been very innovative and creative in their solutions to allow the people to keep on using their libraries, which is really heartening.”

It’s that spirit in all who’ve followed the path of pioneers like Innerpeffray that continues to prove so inspiring for Germaine Greer and countless others.