It can’t have been foreseen how poignant this new exhibition at V&A Dundee was going to be when it was booked for its first and only appearance in the UK.

Opening on Saturday May 1, having been pushed back by lockdown from its intended original opening date last October, Night Fever: Designing Club Culture takes us into the international design history of the nightclub – at a time when Covid-19 has now forced the closure of all nightlife for more than a year.

“Nightclubs are so important to the culture, the last few months have demonstrated that,” says Kirsty Hassard, curator of this Scottish edition of the show; a new part of it will illustrate the relevance of design to some of the most famous new and recent nightclubs across Scotland.

“They still don’t know when they’ll be re-opening, but they’ll be the last,” she continues. “Museums like ours can reopen, but they’re still going to be closed.”

One aspect of the show, she tells us, will be a LiDAR light detection scan of the inside of Glasgow’s Sub Club, with a soundtrack by Jonnie Wilkes, DJ with the ‘Subbie’s classic Optimo Espacio night. “It’s poignant to think of them as empty spaces, when people know them as places of life and joy.”

Nightclubs will return one day, but in the meantime this show – which was devised by curators from Vitra Design Museum in Germany, where it was originally seen in 2018, and ADAM: Brussels Design Museum – is part celebration and part education, not a commiseration.

“It’s really the first exhibition to look at nightclubs as centres and total works of design,” says Hassard.

“That means the architecture, the furniture, the graphic design, the fashion that’s worn to them – it’s a total experience. It’s chronological in its structure, so it goes from 1960 up until the present day, and each of the four sections’ focus is on twenty iconic nightclubs at different periods in time and points of geography.”

The exhibition’s story begins in Italy in the 1960s, with an alternative to the stories of the Swinging Sixties and the American Woodstock generation which we hear about so often. Instead, in Italy a group of radical young architects calling themselves Gruppo 9999 designed a nightclub in Florence in 1969 called Space Electronic, which was to be a boundary-breaking new concept in design, live music and theatre.

In the Tuscan seaside resort of Forte de Miami, meanwhile, Bamba Issa took its design from a Donald Duck cartoon and held a DJ booth which appeared to be suspended on a flying carpet. These were just two notable examples of a wave of designed nightlife spaces which swept the country.

“With the boom of youth culture after the Second World War, life for many people was completely transformed from the late ‘50s into the ‘60s,” says Hassard.

“Mainly in Rome and Florence, but also in some of the smaller cities, experimental Italian architects were trying to think about how they could push the boundaries and what they could do with architecture, but on a small budget. There weren’t a lot of (architecture) jobs, so a lot of them chose to work in nightclubs, and they created these really incredible spaces.

“Then there’s a counter-story to that,” she continues, “which is about the experimentation that was going on in North America at the same time, and the stories of Cyclia and Cerebrum. Cyclia was a nightclub that was meant to be in New York; it was actually designed by the Muppets’ Jim Henson, but it never came into being, it was just a plan for a really experimental space that for whatever reason didn’t end up happening.

“This first section is focused on nightclubs as places where architects and designers could push boundaries and experiment with ideas in the 1960s and early ‘70s.”

The second section, she says, is an immersive installation in its own right, called The Light Inside, which is essentially a silent disco, created by the original exhibition designers alongside lighting and music consultants.

“Obviously one of the main things about nightclubs is music,” says Hassard. “Rather than recreating the interior of any of the nightclubs in the show, they wanted to create this installation that you can walk into and hear the four genres of music that are represented in the show (disco, pre-disco, techno and house).”

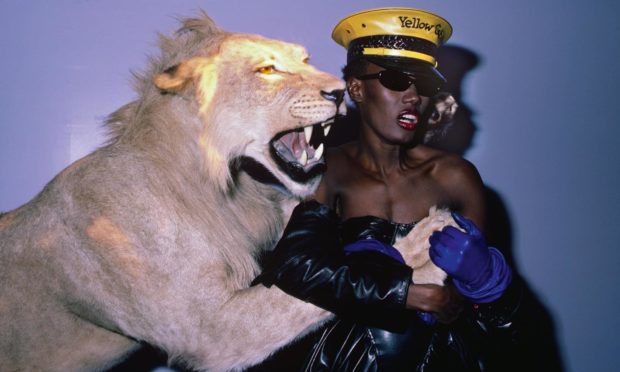

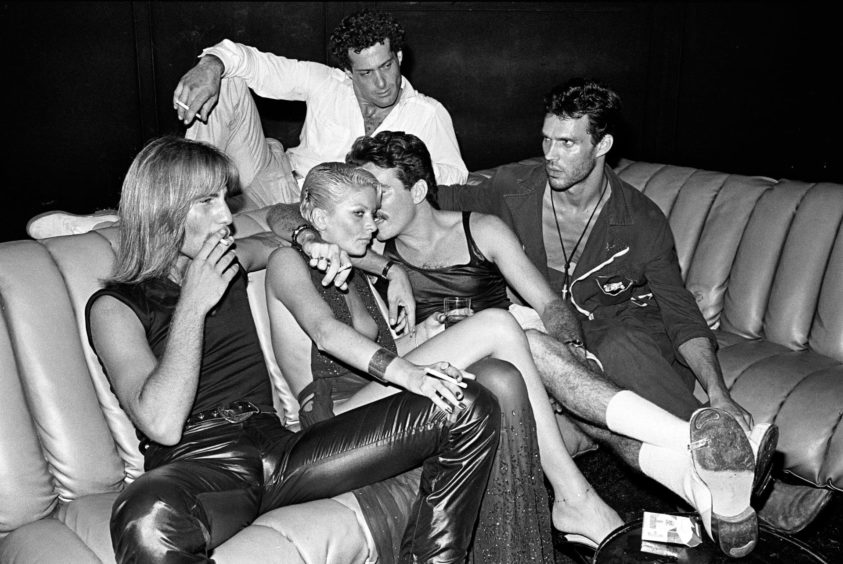

The earliest days of nightclub history as we might be most familiar with them are represented next, first of all with the disco spaces which popularised the genre in New York. “With the rise of Studio 54 in New York came celebrity culture,” says Hassard. “This was the idea that nightclubs are places to be seen, and it looks at some of the people photographed in these places, like Andy Warhol, Grace Jones and so on.

“Then another experimental nightclub in New York was Area, it’s super-interesting. It was around in the early ‘80s, it was famous for changing its interior every six weeks or so. The whole nightclub would be stripped out and they would just completely change it to another theme. We’ve got a slideshow of different nights at that club, and the settings for it are just incredible, they’re so creative.

“(The visual artist) Keith Haring is a massive name who was involved in nightclubs in New York in the ‘80s, he designed the invites for many of them and his artwork was on display in Area and Palladium, in particular. Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well. If you look at New York in that period and the people who attended those clubs, like Warhol and so on, major names in our history were involved – not just to attend them, but actually involved in their design.”

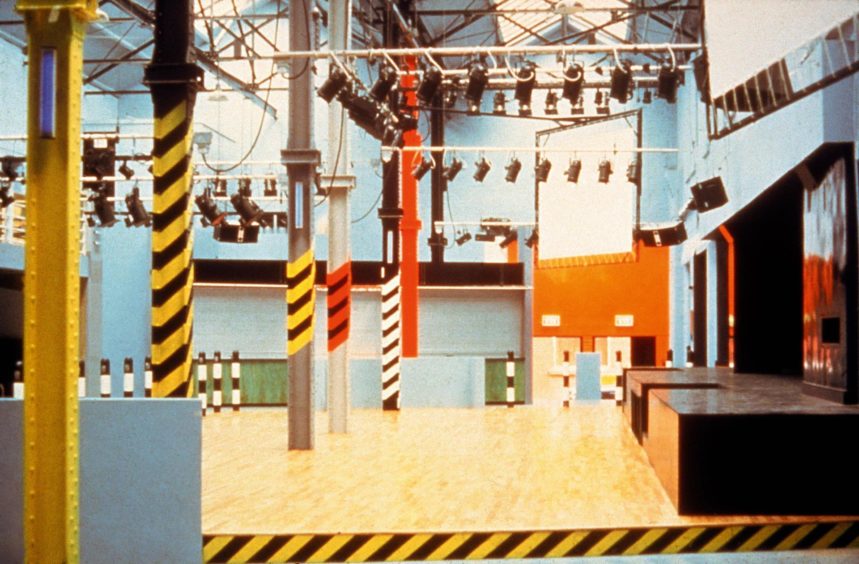

While the first two decades of contemporary nightclub design history shown here are very much focused on continental Europe and North America, the UK comes into its own at the end of the 1980s with Manchester’s Hacienda, owned by the group New Order and indie impresario Tony Wilson.

The place made a strong feature of its designed elements, the creations of Ben Kelly and record sleeve artist Peter Savile, which included roadwork-style bollards and high-vis yellow flashes.

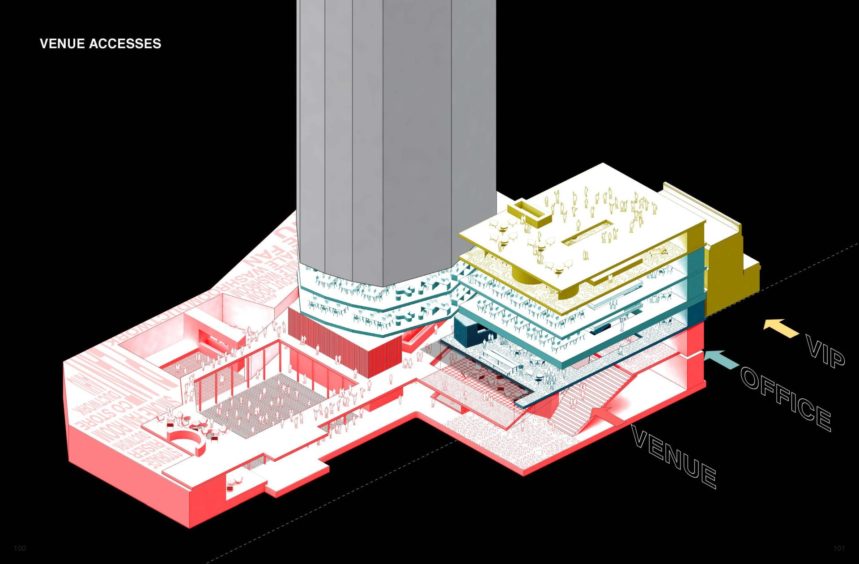

For the final section which has been imported from Vitra, the current fashion for Euro-clubs which has persisted since 2000 is the focus, and in particular destination superclub spaces in Berlin like Berghain and Tresor.

“This part also looks at the idea of nightclubs as being transient spaces,” says Hassard. “That’s become even more apparent recently, with soundsystems and DJs that can move around, and nightclubs which don’t have to be in one specific place.”

On exiting the show another aspect is presented to the viewer, which is about the personal side of attending nightclubs, and also the links which these places bear with the social and political trends of their time. This contains films, including the artist Jeremy Deller’s Everybody in the Place, which is a history of British rave culture of the 1990s and its connections to the politics in the country at the time.

There’s also a specially commissioned film by a Glasgow-based filmmaker called Tim Knights, which looks at amateur footage filmed in Scottish clubs throughout the 1990s and 2000s. “You get this idea of the pure joy of a night out, and the shared experience,” says Hassard. “It feels like… I don’t know, for me anyway, it’s so nostalgic just watching it from what feels like a lifetime ago, when in early 2021 nightclubs have been closed for more than a year.”

The exhibition also includes a 20-metre-long installation by the British artist Vinca Peterson, which is a selection of her photographs, ephemera, leaflets and diary entries from the late ‘90s. Named A Life of Subversive Joy, it’s a record of her life at the time, as she toured Europe with rave soundsystems.

Finally, a section on Scottish clubs created with cultural historian Mhairi Mackenzie features Glasgow’s Sub Club and one of its key – and most individually-designed – nights Optimo Espacio; Club 69 in Paisley; Fever in Aberdeen; and the Rumba Club in Perth, as well as photography of the Sub Club by Brian Sweeney and Locarno at Dundee’s Reading Rooms by Ben Douglas.

This all demonstrates how the contemporary clubs of Scotland looked outside the UK for their design influence, towards Detroit, Chicago and Barcelona.

“The Sub Club only never goes out of fashion because the design’s good,” says Mike Grieve, director of the famous Glasgow club and promoter of the acclaimed Fever in Aberdeen in the early ‘90s.

“It’s been refreshed and updated over the years, and the interior design is absolutely critical to the success of the new Sub Club, I worked long hours with the design team (the Subbie uses the agencies ISO and Graven Images) to get that right.

“The current design background is known as Dazzle Ship, it’s taken from a British Naval design which was used to combat the U-boats – hence the Sub Club connection. There’s a great deal of thought goes into it at every stage, it’s not just a case of, ‘let’s create a nice-looking environment’. There’s always a narrative.

“The cultural impact of clubs in general is often overlooked,” he continues. “That this is being acknowledged in a major exhibition is important. With the Sub Club and Fever, there’s a sense that there’s an alumnus of people in all walks of life who still relate to their youth, misspent or otherwise, in these kind of venues.

“Clubs are a melting point for creative ideas, they’re at the cutting edge in terms of music and design, and that’s been the case since at least the mid-‘80s onwards. Just the fact that we’re talking about this nearly four decades later sets the cultural context for what electronic music and clubs actually are.”

He’s also very conscious that the history of clubs’ impact, in Scotland at least, isn’t confined to the biggest names in the biggest cities; that the contributions of, say, the Rhumba Club, Fever, and Fat Sam’s and the Reading Rooms in Dundee are also recognised.

“I think perhaps people don’t really consider nightclubs as being designed spaces,” says Kirsty Hassard. “I wonder if it’s because you only ever see them when they’re dark?

“That’s the point, obviously. They’re meant to be spaces where you can lose yourself, to be places of escapism, but I wonder if people have made the connection that nightclubs have been so tied to major parts of social history, or that they’re so much a part of people’s development and social lives? You know, my parents met in a nightclub… it’s all intrinsically tied together.”

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture opens at the V&A Dundee on Saturday May 1. See www.vam.ac.uk/dundee for more information.