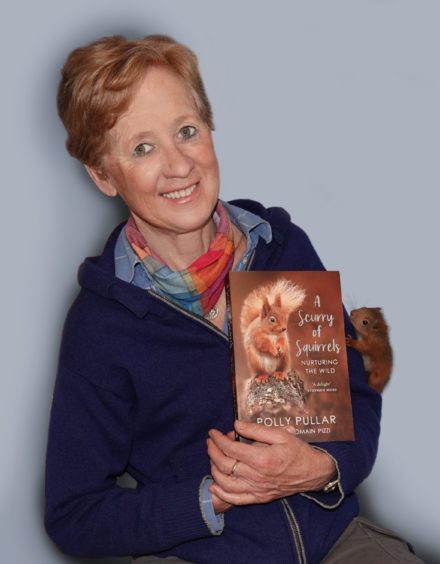

Wildlife rehabilitator Polly Pullar shares her experiences of nurturing red squirrels and other animals in a new book. Gayle Ritchie reports.

Cheeky, bushy-tailed bundles of cuteness – red squirrels are one of the nation’s most adored mammals.

However, we weren’t always quite so fond of the fluffy creatures.

It was legal to cull them until as recently as 1981 and historically they have been hunted and killed in large numbers due to the perceived threat they posed to forestry.

Today, while thriving in some parts of Scotland, red squirrels remain in a precarious state, and it’s a race against time to ensure the long-term survival of the creatures.

Aberfeldy-based wildlife rehabilitator, writer and photographer Polly Pullar has made caring for and protecting red squirrels – and other animals – her life’s work.

Since childhood she has taken in numerous injured and orphaned red squirrels and other wildlife and returned them to the wild.

Growing up in Ardnamurchan on the west coast, she was mad about wildlife almost from birth, but her passion for red squirrels was triggered when she moved to Perthshire.

Hating her time at a boarding school for girls near Dunkeld, she says the creatures were what “saved” her.

“I was very homesick until the wonderful moment I saw my first red squirrel in the school’s extensive garden – that squirrel saved me, and I became totally absorbed by squirrels and spent all my playtimes building dens from where I could watch the squirrels, and the area’s other rich wildlife,” she recalls.

In her new book, A Scurry of Squirrels, Polly shares her experiences and love for the red squirrel, and, with reference to history and natural history, explores how our perceptions of the animals have changed.

Set against the backdrop of her Highland Perthshire farm, where she works continuously to encourage wildlife great and small, the book highlights how nature can, and indeed will, recover if we give it a chance.

In just two decades, Polly’s habitat restoration work has brought about spectacular results, and vast numbers of squirrels (she recently counted 15!) and other animals visit daily.

“Having centred my last book around pine martens, and spent so much of my adult life working closely with red squirrels, it seemed a very natural progression to centre this book on these fabulous arboreal acrobats,” says Polly.

“I have been so fortunate to have come to know them quite well, and most years I take in orphan kits, or injured adult squirrels with the goal of eventual return to the wild.”

Polly struggles to absorb the fact that up until 1981, when red squirrels were added to the Wildlife and Countryside Act and became legally protected, it was still, in her words, “perfectly acceptable” to cull them.

“People thought they were a threat to trees and they were hunted for their tails with a bounty paid for squirrel tails,” she says. “Some keepers actually cut off the tail and set the squirrel free again in the belief they might be paid twice!

“But squirrels of course do not regrow their tails, and as the tail acts almost as a vital fifth limb and is used like a tightrope walker’s balancing pole, as a parasol, umbrella and for signalling mood and intention to other squirrels and to threatening predators, this must have been catastrophic.

“Squirrels were also hunted for their pelts. Indeed, at Perth Market a stall set up by the Marchioness of Breadalbane had hundreds of skins for sale!”

In 1903, Beatrix Potter wrote the Tale of Squirrel Nutkin which was hugely successfully in endearing people to the creature.

However, at the same time, the Highland Squirrel Club was on a mission to get rid of squirrels; between 1903 and 1929 they culled 82,000.

“There were all sorts of organisations trying to get rid of red squirrels, whether by shooting, trapping or using catapults,” says Polly.

“It’s extraordinary how perceptions change and thank goodness they do. They were once seen an enemy and now they’re regarded as darlings.

“And why wouldn’t you adore such an enchanting little rodent? It’s astonishingly acrobatic – a sylvan tightrope walker, stunningly attractive with its beautiful auburn coat and lovely tail, and also very cheeky and mischievous, full of devilment.”

People thought they were a threat to trees and they were hunted for their tails with a bounty paid for squirrel tails.”

Polly Pullar

Today, red squirrel populations face drastic and continual loss of habitat. Domestic cats and dogs can pose a huge threat, as can our ever-expanding road network.

But one of the worst threats is the non-native North American grey squirrel, introduced to the UK at the end of the 1800s as a curiosity to grace large parks and estates in the south. Soon after, the species was brought to Scotland and spread at an alarming rate.

“It’s important to understand that the grey does not physically kill the red, but it is larger, more robust and able to out-compete the red for a dwindling natural food source,” explains Polly.

“Greys can also eat many foods before they are ripe enough for the more sensitive digestion of the red, and therefore nothing is left.

“But worst of all is that the grey carries the insidious squirrel pox virus and though it does not affect it, it passes it to the red.

“It’s a fatal virus that looks similar to myxomatosis in rabbits. Basically, it will wipe out a population of reds within a very short time frame. Few, if any, survive.”

Scotland holds 70 per cent of the UK population of an estimated 140,000 to 160,000 red squirrels and in some areas they are thriving, but they remain in a precarious state and desperately need more connected habitat – safe places to travel between suitable woodland.

“It’s a problem. Small isolated populations become marooned as if on an island and soon die out as their habitat shrinks. Their future is not secure,” laments Polly.

So what can people do to help? Polly suggests putting out feed for them in our gardens, but also considering not doing so if you live close to a road, which might encourage them to cross, putting them in peril.

She also believes keeping dogs under control in wooded areas and putting elasticated collars on cats with loud bells will help.

“Squirrels are pretty stupid and often slow on the ground, and cats can easily stalk them – bells can help avoid disaster.”

Having been around squirrels for as long as she can remember, Polly has experienced many happy – and sad – moments.

Her happiest was the day she released the youngest babies she’d ever hand-reared, four-day-old kits.

“They were bald, deaf, blind and totally dependent on arrival,” she recalls.

“After a summer dominated by their round-the-clock care, I released them in our garden.

“I had tears in my eyes as they climbed up the tallest tree. That was a happy day as I never thought we would ever reach that goal – getting them back to the wild where they belong.”

In terms of saddest moments, Polly says she’s had “too many”.

Recently, she found a wild squirrel run over by a delivery person in her drive.

“I was devastated. Right by the body was our sign saying: ‘Slow down for red squirrels’. I cried.”

Polly, an advocate for habitat restoration, planted more than 5,000 trees and dense hedgerows on her farm 21 years ago and leaves huge areas wild.

“I let nature manage nature. Nettles, dandelions and brambles are invaluable.

“Nettles are a vital food plant for many caterpillars of the butterflies we adore, dandelions are nectar and pollen-rich and invaluable to pollinators, while brambles provide so much – habitat and nesting sites, pollen, food and are always alive with dozens of invertebrates.

“Without invertebrates the entire food chain is thrown out – and this is part of our sinister biodiversity crisis.

“So, we need to change our mindsets and stop our tidy gardening. Our frenetic grass cutting and strimming leaves a barren desert, and an impoverished sward where nothing can thrive.”

Across Scotland, there is excellent work going on to restore and preserve habitat, and to ensure the grey does not come in.

“It’s hard to explain to people that the removal of greys is paramount if we want to retain our reds,” says Polly.

“I struggle with the idea of culling it too, as the grey is here through no fault of its own.

“Humans are inveterate meddlers and where we meddle there is always trouble – the introduction of species from elsewhere will almost always lead to trouble and I feel sad that the grey is the victim.”

While keen to get the message across that her book is not just about squirrels – “there are stories about owls and deer and many other animals I’ve rehabilitated” – Polly hopes it will open the hearts and minds of readers to the fact that “without nature we are nothing”.

“I long for them to make that connection, and through the stories I tell, I want them to understand that animals are also sentient beings, and we need to nurture them and their natural environment as never before.

“I often hear the phrase ‘the wildlife will go elsewhere’, when someone is cutting down a wood, pulling up a hedge, or draining a bog. And my question is always ‘where?’.

“We have to learn to live our lives in harmony with nature and not as separate entities.

“I was intrigued lately to learn that many ethnic societies have no word for ‘nature’.

“That is because they do not think of themselves as being separate from it. Does that not say it all?”

- A Scurry of Squirrels by Polly Pullar is published by Birlinn, priced £14.99.