There’s nothing we can write about last Sunday’s UEFA European Championship 2020 Final that hasn’t been pored over in fine detail by now, but amid debate over footballing machine / weapon Giorgio Chiellini’s cynical shirt-tug or Gareth Southgate’s choice of penalty-takers, it’s worth pausing to flag the viewing figures for the British television event of a generation.

The next day’s reports had it that 25m viewers tuned in on the BBC and 6m on ITV, making the final both the largest live television audience since the funeral of Princess Diana in 1997, and a firm repudiation of Sam Matterface and Lee Dixon’s laddish sloganeering commentary partnership for the latter.

Still, at least a generation have a new unifying experience to look back on which isn’t a global pandemic.

Secrets of an ISIS Smartphone

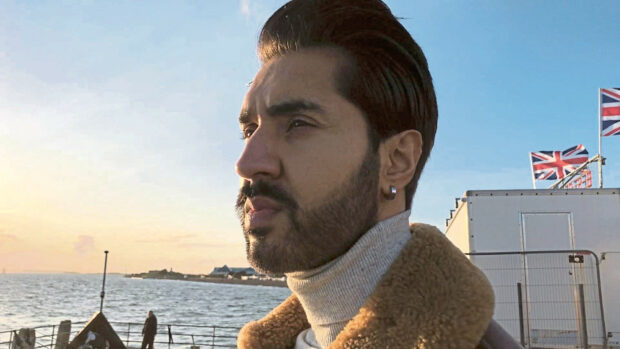

Laddishness of a very different and fatally toxic kind proved to be the subject of the enthralling but disturbing Secrets of an ISIS Smartphone (BBC Three). In it, television journalist Mobeen Azhar (Hometown: A Killing, The Battle for Britney) gets his hands on a hard drive full of smartphone material recorded by three British Muslim men who travelled to join ISIS in the warzones of the Middle East over the last decade.

The most striking artefacts displayed here are phone videos of these young guys – bright-eyed and even humorous, not what we’d expect at all – larking around in the sun with weapons as though they were workmates on a live-fire paintball weekend, influenced by video games and horror films far more than religion. This relatively tame interpretation of ISIS life is used by Azhar as a springboard to contact (or attempt to, as family members avoided speaking) a number of people with personal insight into these characters in the UK.

What we’re left with is a story not of wild-eyed fanatics, but rather young Brits who might have mental health problems, feel disenfranchised from society or even just be too young to know who they really are yet, who have essentially been groomed online. It’s neither a definitive history of the subject nor a forensic examination of the recovered material, but Azhar’s film does open a window on a world of uncomfortable complexities. Of the 900 Britons who fled to join insurgent groups between 2012 and 2018, the three featured are among the 180 now dead.

Our NHS: A Hidden History

Alienation in modern Britain is also a feature of Our NHS: A Hidden History (BBC One), in which the increasingly ubiquitous and comfortably authoritative historian David Olusoga examines the often-unrecognised role of migrants in the building and smooth running of the NHS.

We hear uncomfortable tales of Caribbean nurses experiencing racist mistrust from colleagues and patients; the importance of migrant doctors, to the extent that the UK Government was concerned a 1965 military skirmish between India and Pakistan might see an exodus of staff and collapse the system; and the shifting of ‘overseas’ and Irish professionals into undesirable jobs, even as their presence filled shortage gaps and helped the NHS operate.

Like Azhar’s film, Olusoga’s can only start the conversation. Yet the instinct to care’s universality – now more than ever – is tangible, from the birth of the NHS to the moment one of the service’s 20,000 Filipino nurses delivered the UK’s first Covid vaccine and beyond.