Low water levels have revealed a secret landscape of abandoned bridges, roads and farmhouses normally submerged in Scotland’s reservoirs. Gayle Ritchie investigates.

Deep in the heart of remote Upper Glendevon, the lonely, crumbling ruins of a shepherd’s farmhouse bask in the sunlight.

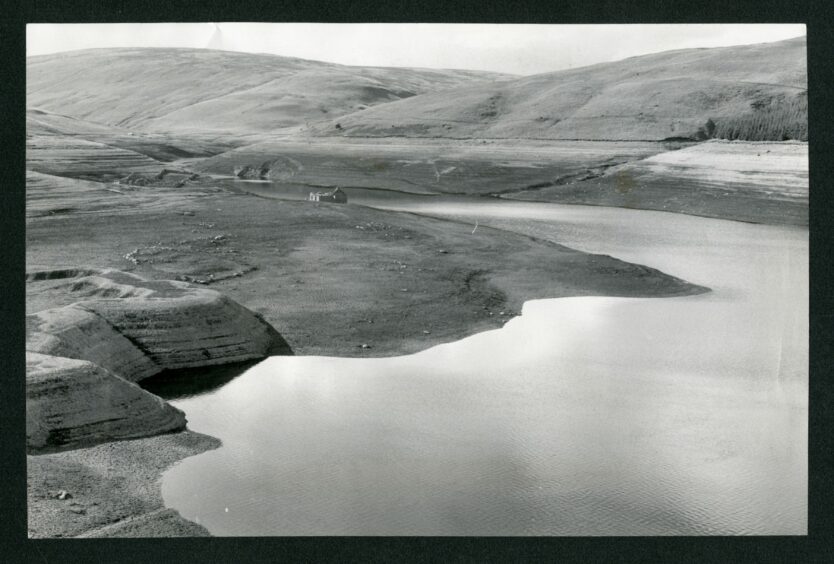

Dried out and caked in mud after almost 70 years of being submerged underwater, the farmhouse, along with its scattered drystane dyke shielings, is a uniquely poignant and somewhat surreal sight.

A toppled chimney, rusted drainpipe, remnants of fireplaces, and even wooden lintels can be seen inside the tumbledown building.

Nearby, a line of wooden fencing sinks into the mud while shoots of grass grow on the cracked, parched earth as the land attempts to return to its natural state.

It’s a rare spectacle but once in a while this lost landscape reveals itself, emerging from the valley as water levels in Upper Glendevon Reservoir fall.

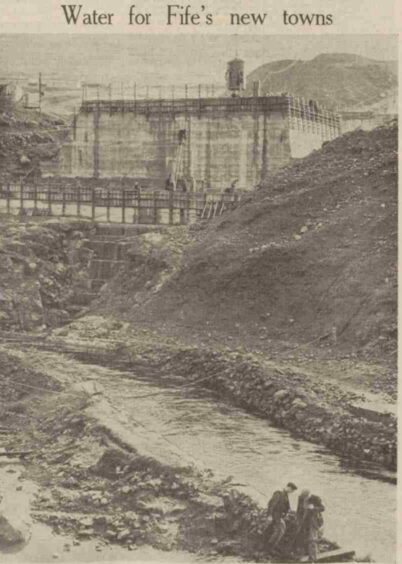

The buildings were “hidden” in 1955 when the River Devon was dammed and the isolated glen in the Ochil Hills was flooded to create a reservoir which would provide drinking water for large parts of Fife.

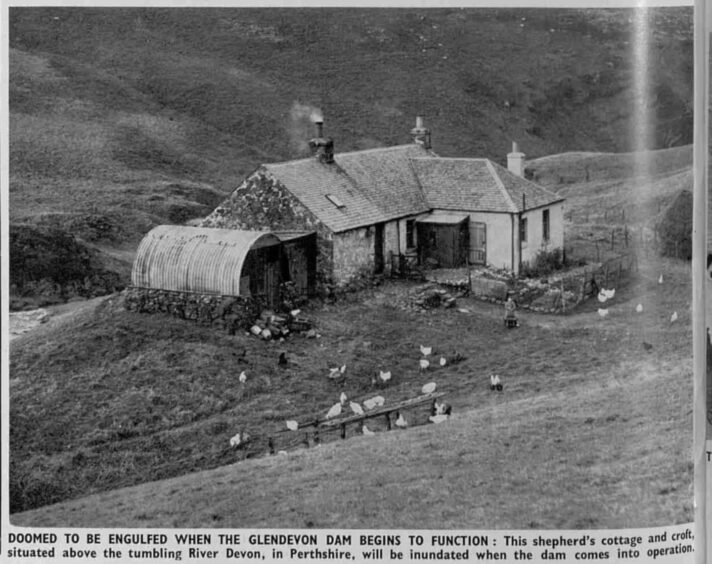

A report in illustrated weekly newspaper The Sphere on November 8 1952 featured a photograph of the enchanting whitewashed dwelling before it was drowned, with smoke puffing from a chimney and a young boy feeding hens in the garden. The black and white picture bore the rather foreboding caption: “Doomed to be engulfed”.

The reservoir is part of a network of five carved out of the dramatic Perthshire landscape and holds around 4,844 million litres of water, held back by a 45-metre high dam.

Abandoned

Farmer Colin Campbell owns the abandoned farmhouse, Backhills Farm, and the surrounding land.

His great grandmother bought the farm in the late 1940s and rented it to shepherds who tended sheep on the land.

“It became a struggle to get folk to live in it ultimately,” he says. “There were no roads up to it – only farm tracks.”

The last family to live in Backhills were the Haliburtons. And in fact, the photograph above, of the farm in 1952, shows Dan and Helen Haliburton’s grandson Robert Black in the garden.

Robert was almost seven years old when the Haliburtons left Backhills before the glen was flooded and the family moved to Rannoch in 1954.

Now 74, he is lead fireman in Kinloch Rannoch and runs a joinery business with his son James.

His wife, Joan, says the family had been very happy at Backhills and were not at all lonely living in such a remote spot.

“The Haliburtons were very sociable people and had friends and relatives to visit often,” she says.

“Being a shepherd Dan and Helen (Nan) had been in remote areas quite a lot of their married life; it did not bother them.

“We are of course talking about a different era – there were no supermarkets so shopping was done locally. Dan and Nan loved it at Backhills and were sorry to leave although they had some problems, as we have today, with fishermen knocking down fences and starting fires, like the ‘dirty campers’ we have in Rannoch nowadays.”

Colin Campbell and his family moved into the replacement farmhouse, higher up the glen and above the reservoir, in 1961, six years after Upper Glendevon was engulfed.

He flitted a few years later to make way for a wind farm (it was felt the turbines were too close to habitation) but the house still stands and is used as an office.

Today Colin lives in Blackford but he visits Upper Glendevon often, and frequently sees the farm buildings emerging as water levels recede.

A report in the Press and Journal on September 3 1974 during a drought referred to the “cracked, baked ground” of the reservoir, which was only a third full.

It stated: “A drop of 65,000,000 gallons has left a once-submerged cottage crouched at the water’s edge.”

Underwater ruins

Photographer, artist and film-maker Calum Gillies drove from his home on the Isle of Raasay to explore Upper Glendevon Reservoir as part of a special project.

“I’ve been keen to do something on ‘underwater ruins’ for a while,” he says.

“I specifically drove to Upper Glendevon, a five-hour-trip in my campervan, to check it out.

“I got there at the perfect time. Barely a muddy puddle was left at the base of the dam.

“The most amazing sight was the old farmhouse, drowned in the 1950s. It was like a time capsule sitting at the bottom of the dam.

“The light was striking down and illuminating it and I was able to wade my way through mud to get inside.

“As well as the farm, with its collapsed chimney, old wooden lintel, iron-wrought guttering and graffiti from the 1990s, there were little shielings, huts and an old quarry.”

Reflecting on the “wasteland” now dominating the view down the glen from the farmhouse’s gaping windows, Calum imagines how once upon a time – not that long ago – the scene would have been breathtakingly beautiful.

“It’s strange to think of all the stones, slates, tiles and bricks that would’ve been moved up here and the work, effort and money that went into building this.

“To find it’s been swallowed up by the hydro-schemes within decades is sad.

“When I visited in mid-September, everything was covered in silt and stained white in mud; it was like the water had removed the colour.”

Previous examination of the landscape found two possible prehistoric burial cists and a motte, or mound, which may have been home to a structure or camp.

Calum found the contrast of the dam with the wind farm perched high above the reservoir a “wonderfully poetic” way of summarising large-scale industrial changes to the landscape.

“It was an interesting comparison – standing underneath a dam looking at the future of power in the 1950s and then looking up to see the modern future of power,” he remarks.

“The family who lived in the farmhouse were told to leave to make way for the reservoir and the family who lived in the cottage below the wind farm also moved out. It’s strangely ironic.”

Calum, 29, who graduated from Abertay University in 2014 with a degree in creative sound design, turned his stunning footage and photos into a YouTube documentary – Scotland’s Submerged Ruins – which also shines a spotlight on the man-made reservoir of Loch Cluanie in the Highlands.

He suspects “lost landscapes” will reveal themselves much more often as a result of prolonged dry spells and climate change.

The most amazing sight was the old farmhouse, drowned in the 1950s. It was like a time capsule sitting at the bottom of the dam.”

Calum Gillies

Drowned

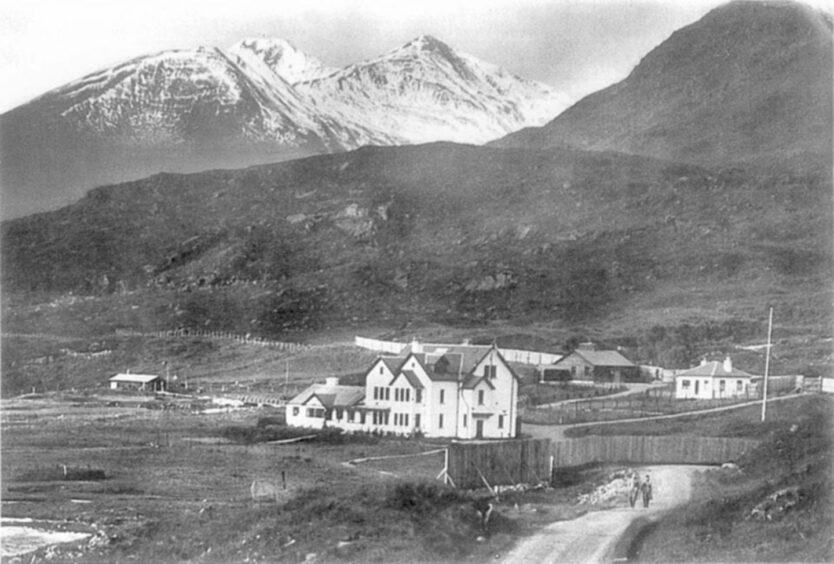

On rare days, when Loch Cluanie is at its lowest, two chimney stacks poke out of the dark, glassy waters like strange pillars.

They are the remains of a laundry house attached to Corrielair Lodge, a sprawling Victorian shooting lodge which was demolished when the glen was flooded in 1957 to make way for a reservoir and dam to generate hydroelectricity.

Close to the chimneys are the desiccated stumps of old trees, and a road to nowhere, disappearing over a dilapidated stone bridge into the loch.

Writer and broadcaster James Crawford reckons this strange, otherworldly vision, which offers up relics of a by-gone era, is best understood from above.

He told the fascinating story of the loch’s transformation in the first series of Scotland from the Sky, a BBC One Scotland production which first aired in 2018.

In the series – an exhilarating mix of aviation adventure and historical detective work – James took to the skies to explore the country, combining modern aerial shots with rare archive material from Scotland’s National Collection of Aerial Photography to tell the story of the making of a modern nation.

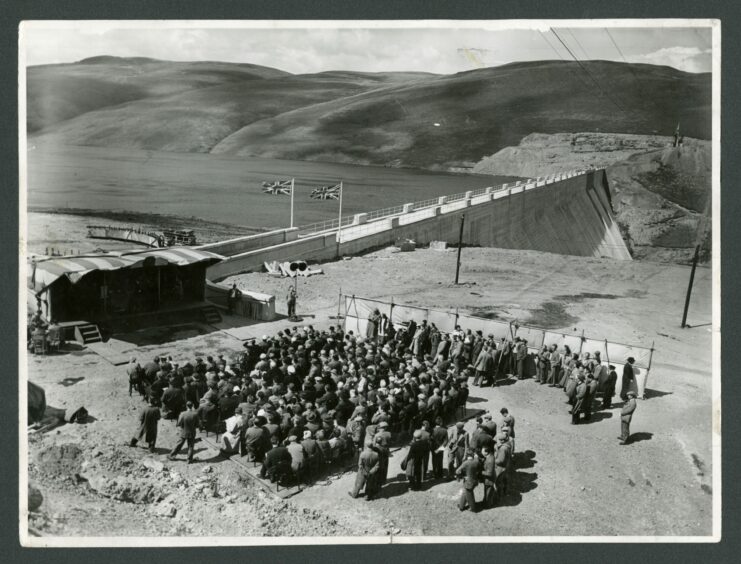

One of his most striking discoveries was just how much Scotland’s post-war hydro schemes – which raised water levels to build dams and create electricity – transformed the landscape and affected communities.

“In the post-war period, the hydro schemes raised Loch Loyne and Loch Cluanie significantly – up to 30m – and drowned roads,” says James, who grew up outside Auchterarder.

“We drove to the end of the line at Loch Loyne to watch the tarmac disappear down into the loch. We also saw the crumbling remains of an old Telford bridge, now a bridge to nowhere.

“A 1940s RAF aerial survey of every inch of Scotland was used to identify the best sites for the hydro schemes. In the 1950s, people were told ‘this valley is going to be flooded – you have to move out’”.

Loch Cluanie of today is a mesmerisingly beautiful, yet curious, sight from above, particularly when the water is low.

Trees on the shores were cut at the base before the planned flooding so their tops wouldn’t poke up above the water. Today, during dry spells, you can spot their twisted stumps.

But most powerful of all are the two chimney stacks, rising up from the underwater laundry.

“A former gamekeeper who grew up in a croft beside the loch remembers playing there as a boy, and playing shinty on the road outside it,” says James.

“He has vivid memories of driving on the road with his dad for the last time, to find it had been washed over.

“On one hand, the planned flooding was essential – it brought electricity to the Highlands – but it’s easy to forget that it caused a fundamental transformation of the landscape, which impacted communities.”

Community

Rhuaridh Campbell, head gamekeeper at Cluanie Estate, wonders how long the old laundry and its iconic chimneys will stand.

“Some of the buildings were falling to ruin before the dams but there used to be a wee community here,” he laments.

“The buildings would have been at least 60 years old prior to them coming down and probably in need of repairs. There were houses here and there throughout the glen, many of which would’ve been swallowed up by dams.”

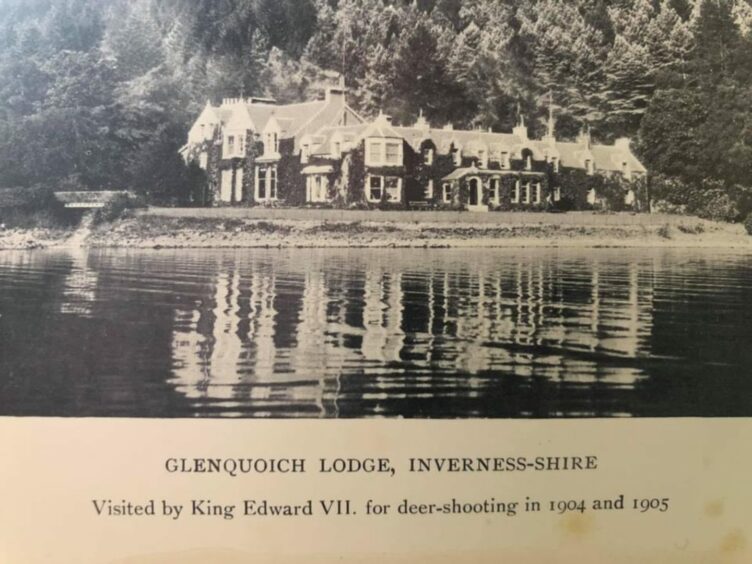

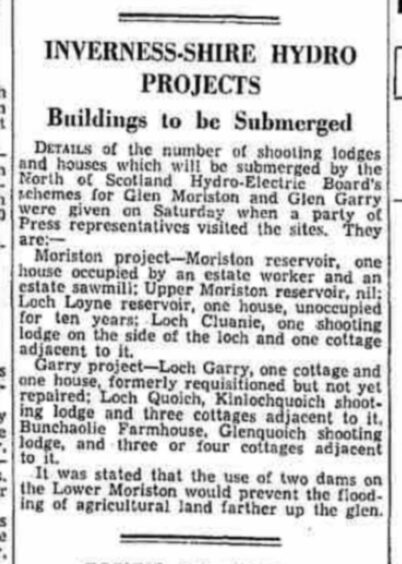

As well as Corrielair Lodge, which was demolished before the construction of Loch Cluanie, there was beautiful Glenquoich Lodge, 40km north-west of Fort William. King Edward VII stayed there in 1904 and 1905 while on holiday indulging his passion of shooting deer.

The lodge was torn down to make way for man-made Loch Quoich reservoir as part of the 1950s Glen Garry hydroelectricity project.

“Looking back, they were way ahead of their time for green energy,” reflects Rhuaridh. “It’s fascinating to look at old photos of what’s been lost, or to see actual physical remnants.”

Ghost road

Up until the 1950s, the main road from Inverness to Ullapool ran through the middle of Glen Glascarnoch, but the glen was dammed to create artificial Loch Glascarnoch to hold water from Loch Vaich and Loch Droma, before feeding into the hydro system at Mossford Power Station, five miles away.

This old “ghost road” re-emerged in 2015 when SSE lowered the water level in preparation for heavy rains.

“I took a photo of it last year because the loch was incredibly low and this old bridge had appeared – for the first time in decades I think,” says James.

Hydro power

Between 1946 and 1965, some 54 new power stations and 78 new dams were built across the Highlands.

The Gaelic motto of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board was “Neart nan Gleann”. Power from the Glens.

“What this really meant was landscape manipulation on a massive scale,” reflects James.

“To produce ‘power’ from the glens you had to flood them – and many of them were not empty.

“These are the lost stories behind the drive to bring electricity to many remote parts of the country for the first time. And they are a reminder that progress rarely comes without consequences.”

James feels there’s something “uniquely poignant” about seeing traces of the past – houses, roads, bridges – emerging from beneath the waters of a loch.

“It’s like a secret revealed, perhaps for weeks, perhaps just for days, before the rain comes again, and those traces disappear. Sometimes, even for generations.

“If you get a chance to see them, you know that it may genuinely be a once-off. And that makes them especially charged as remnants of our past.”

INFORMATION

- A Scottish Water spokeswoman said: “Upper Glendevon reservoir is one of five reservoirs that make up the Glendevon supply system and the water level of this particular reservoir tends to drop to low levels most summers. The combined storage of the overall Glendevon reservoir system has been below average for the time of year in recent months, but has remained within normal operation range with no immediate concerns. The exposure of the old farm buildings occurs at low water levels and has been seen quite frequently in the past. As we move into autumn, we encourage customers to continue to use water efficiently to help reservoir levels to recover after a dry summer.”

- Check out Calum’s film at youtube.com/watch?v=uhaYomOWmnM

- The third series of Scotland from the Sky runs on November 1, 8 and 15 at 9pm on BBC One Scotland.