To most of us, the Queen is the one great constant in British life. For 70 years, through 12 or more prime ministers and thousands of events, she has been the one sure anchor point.

Everyone admires her unshakable sense of duty.

She has fulfilled her head of state role so well, without putting a foot wrong, that she commands global admiration and respect, even in lands that are staunch republics.

That sense of duty is undoubtedly her own, but it also stems from her parents, King George VI and The Queen Mother.

Their great sense of duty, during arguably the most difficult times in UK history, was the example the Queen has looked up to all her life.

Never expected to be king

Yet King George VI never expected to be king, was never trained as heir-apparent and had to step unwillingly into the role in December 1936.

He was born Albert Frederick Arthur George on December 14, 1895, the second son of the man who became George V and his consort, Princess Mary of Teck.

His elder brother was Edward, later briefly Edward VIII, and the two were like chalk and cheese.

Edward was slight of build, but over the years gained a self-confidence and ease of manner in public that made him a very popular Prince of Wales.

When invasion fears were rampant and many urged them to move to Canada, that idea was promptly quashed by the Queen.”

Albert, inevitably called Bertie, was taller, shy, awkward and—aggravated by his father’s frequent bullying—had a severe stammer that stayed with him for years.

The boys’ parents were aloof, cold and distant, so they were brought up, as were so many high-born children, by a string of nannies and later private tutors.

Until 1910, when their father became king after the death of Edward VII, they all lived at York Cottage, one of the big houses on the Sandringham estate.

On reaching their teenage years, both boys were packed off to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, following in their father’s footsteps.

Plagued by ill health

Neither of them did that well at Dartmouth, indeed Bertie emerged second from last in his final year.

His poor showing was partly due to ill health—for years he suffered from severe gastric problems, possibly stemming from his childhood.

However, he was good at sports—he played at Wimbledon in the 1920s—and was said to be a crack shot.

In 1905, Bertie attended a children’s party in London.

Another guest was Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, then aged five, the lively youngest daughter of the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, of Glamis Castle, St Paul’s Waldenbury in Hertfordshire and a London house near Berkeley Square.

Whether they actually met is a moot point but they certainly did so after the First World War.

The war had proved a miserable one for Bertie but an early high point for Elizabeth.

In 1914 he was posted to HMS Collingwood at Scapa Flow but his gastric trouble quickly brought him to Aberdeen, his cot being craned from ship to dockside, to be rushed to hospital for an appendectomy.

His health stayed poor (it took years to diagnose a duodenal ulcer) and he spent the winter of 1915 at Sandringham with the king, stricken with a broken pelvis after falling from a horse.

Learning the ropes

Those months taught him a lot about the monarch’s responsibilities, greatly aiding him 21 years later.

Also, he and George V established a good rapport neither Edward nor his other siblings ever achieved.

He later returned to Collingwood, took part in the Battle of Jutland, but was finally invalided out of the Navy. He then briefly joined the fledgling RAF.

The war allowed Elizabeth to shine, as Glamis Castle became a recuperation hospital for war-injured.

Her mother Cecilia initially took charge but, distraught after her son Fergus was killed at the Battle of Loos, she took a back seat.

Her teenage daughter’s charm, hard work and sympathy enchanted all the injured men. She also showed remarkable initiative during a fire on an upper floor.

Bertie and Elizabeth met again in May 1920 at a party in London—and he was smitten from the first moment.

However, she was not impressed by this awkward, moody would-be suitor, neither were her parents overawed by royalty or her marrying into it.

While at Balmoral, Queen Mary—determined to assess the object of Bertie’s adulation—visited Glamis, where Elizabeth hosted afternoon tea as her mother was ill.

Queen Mary was totally won over, but it still took Bertie nearly three years and three proposals to win her hand.

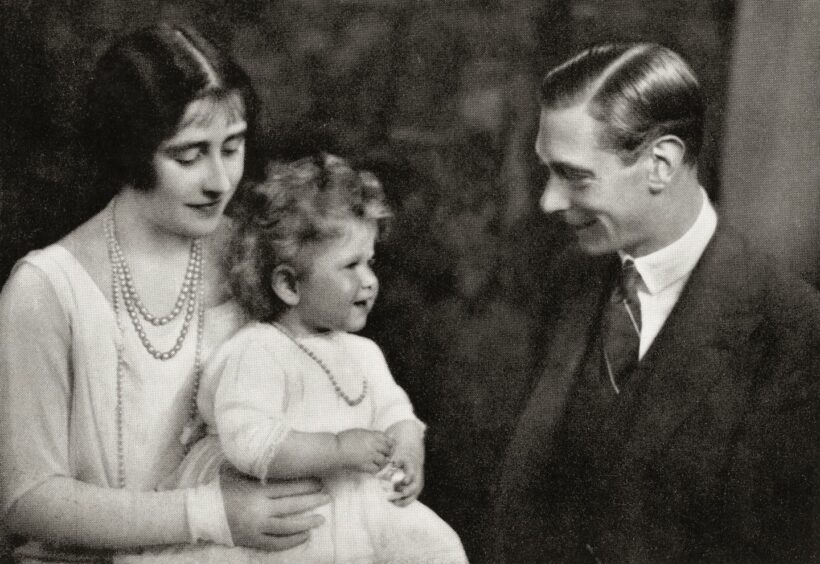

They were married in 1923 and their first-born, Elizabeth, arrived in April 1926 and in August 1930, Margaret was born at Glamis Castle.

‘Duty is the price one pays’

Two qualities Bertie, now Duke of York, and Elizabeth shared were a deep faith and a strong sense of duty, her mother once saying, “Duty is the price one pays for privilege.”

They tirelessly toured the Empire (as it then was) and carried out hundreds of engagements from Exeter to Elgin and beyond.

Elizabeth sought help to cure the Duke’s stammer and eventually located an Australian speech therapist, Lionel Logue, who succeeded where others had failed—wittily portrayed in the film, The King’s Speech.

The Yorks might have stayed unobtrusive second-rank royals but for the death in January 1936 of George V and the arrival in 1931 in Edward’s life of one Wallis Simpson.

Thousands of books have covered every detail of their story but the cold upshot was that on December 11, 1936, Edward abdicated and a bewildered Bertie became king.

Not since the early 19th Century had anyone come to the throne under more difficult circumstances.

Britain was deeply split over the abdication, many were still jobless after the Great Depression, fascist Germany and Italy seemed unstoppable and (now forgotten) mainland Britain was enduring an IRA terror campaign.

Not an easy time

After their May 1937 Coronation, as the new King and Queen visited Belfast, a hand grenade was thrown and exploded near them.

Now King George VI, he was acutely aware of the lingering popularity of his elder brother and that he lacked his public charm and persona.

But gradually, staunchly supported by Elizabeth, he made progress. Two state visits, to France and to the US and Canada, were very successful.

Of all events that consolidated the relationship between King and Queen with the British people, it was the Second World War.

Both resolutely stayed at Buckingham Palace throughout the Battle of Britain and the Blitz and visited those areas worst hit by the nightly bombing.

Indeed, when the palace was bombed, the Queen said that “at last she could look the East End in the eye.”

When invasion fears were rampant and many urged them to move to Canada, that idea was promptly quashed by the Queen.

The King and Churchill

Fears that the King’s relationship with Churchill might be strained (Churchill had strongly supported Edward in the abdication crisis) proved misplaced — very quickly they achieved a strong rapport and mutual respect.

Churchill may have been the driving engine of HMS United Kingdom, but the King and Queen were the vital flags on the masthead.

The post-war years should have been happy ones.

In November 1947 their beloved Elizabeth married Prince Philip of Greece, whom she had met years earlier at (coincidence, coincidence) the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth.

Longest royal marriage in history

It is said both King and Queen had doubts about her choice of consort, but that marriage proved as solid and enduring as theirs.

It was to last almost three quarters of a century, the longest royal marriage in history.

However, the post-war years were overshadowed by the king’s declining health, not helped by his being a lifelong smoker.

A demanding Royal Tour of South Africa in 1947 was to be his last foreign trip, during which Princess Elizabeth made her famous broadcast pledging that her entire life would be “devoted to your service.”

In January 1952, Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip flew from London on a tour of Australia via Kenya, as King George was too frail.

But he stood at the airport in the biting wind and watched their plane slowly disappear into the grey sky. Somehow he knew he would never see his daughter again.

A week later he died in his sleep at Sandringham, aged just 56.

His widow, now remembered as the Queen Mother, was to die more than 50 years later on March 30, 2002.

During their relatively short 15-year reign, George VI and Queen Elizabeth helped in their self-effacing way to hold Britain together during the most turbulent years of the 20th Century.

Now half-forgotten, their example and legacy are, thanks to their daughter, still very much with us.