At John White & Son’s base in Auchtermuchty stands a weighing scale that was built in the year the company was founded.

It was put together with such precision and care that, 301 years after it was made, the scale still weighs virtually as precisely as when it was new. Look closely and you see a single penny resting at the end of one arm – all that’s needed to counterbalance the timeworn steel.

“That scale is still accurate enough to pass current tests today,” director Edwin White beams.

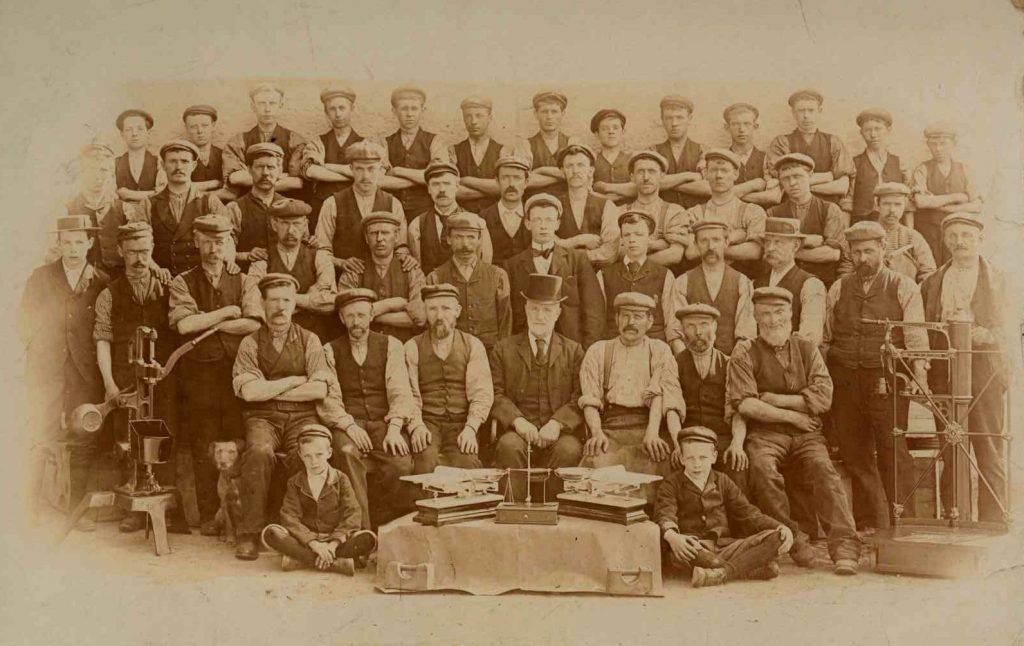

John White & Son was set up by Edwin’s great, great, great, great, great grandfather in 1715. A White has run the company ever since then and Edwin, 72, is the eighth generation of his family to have stood at the helm.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries the company’s main customers were farmers, who used its scales to measure sacks of grain and cuts of meat.

With weighing now rarely done on site at farms, today’s company’s has clients in the quarrying industry and works with almost all of Scotland’s established whisky distilleries.

Sadly, the White line looks set to be broken when Edwin finally retires. “The company gained its first non-family managing director in March when I stepped down from the role. My children have both chosen different paths in life.

“It is a bit of a sad thing but that’s the way the modern world is. And while it is the end of an era we’ve got great staff so the firm’s in safe hands. Our family still owns the company and we will retain a close interest in it.”

It’s also planning Auchtermuchy’s first museum – the Museum of Weights and Measures is due to open in an outbuilding on the firm’s site next year.

Twenty-nine might seem young to be already well established as a director of a furniture chain employing more than 160 people.

But Gillies of Broughty Ferry marketing director Ewan Philp has been working in the family business for the best part of two decades, gaining the experience he needs to help spearhead the company.

He’s one of five family members who work for Gillies. His father Ian is managing director and his uncle Alastair is sales director. His two cousins David and Christopher are operations director and distribution director.

Ewan spent his childhood learning about the business from the older generation. “I’ve been doing stuff for the company since I was 12,” he smiles. “Putting stickers on leaflets and tidying up. I’ve had paid jobs since I was at school.

“I’ve done everything from sweeping up the warehouse to deliveries and summers doing sales when I was at university.”

Ewan has worked full time for the company since graduating from Robert Gordon University in 2008 with a degree in retail management.

“I’ve worked my way up as assistant manager and general manager. I’ve done pretty much every job there is in the company, at all levels. That’s important for getting people’s respect but it also means I’ve done all the jobs so I know when we’re pushing an employee too hard or not hard enough.”

The company was set up by 26-year- old James Gillies in July 1895.

It was on Perth Road for its first decade but James was deeply attached to Broughty Ferry and moved the business there in 1906.

James Gillies’ daughter Sheila’s married name became Philp and the business remains in the family hands 121 years after it was set up. Ewan is James’ great, great grandson.

Today, Gillies has four stores: the Broughty Ferry flagship, Perth and Aberdeen, and a flooring shop in Montrose. Gillies continues to prosper long after other family owned local furniture shops such as DM Brown, Draffens and GL Wilson have been driven out of business by retail park stores. “Being part of the community is important to us,” Ewan says. “We have a lot of footfall outside and people can walk in – they don’t need to take a car.

As Gillies’ management hands roles down the generations, so do its customers hand the baton on. “We have great, loyal customers,” Ewan continues.

“Grandparents come to us, then parents come to us and a few years later their children come to us.

“If you work here long enough you see generations of customers.”

Part of the company’s success, Ewan says, is his Uncle Alastair’s knack of finding product lines no one else has. “He travels all over Europe and the Far East to trade fairs. He’s brilliant at sourcing great suppliers. My dad sources flooring. He doesn’t get to travel to quite as exotic locations for that. Last week he was in Harrowgate…”

Each festive season Gillies enormous Brook Street window is given over to a Christmas display. These have grown in scale over the years and are now a mainstay of Broughty Ferry’s Christmas celebrations.

“We’ve planned the display already and this year’s going to be even more special than ever,” Ewan grins. “But I can’t tell you a thing about it.”

In no industry is a job so frequently passed down from father to son as farming. That’s changing, though, reckons Iain Fairlie.

“When I was a lad it was pretty much expected of you that you’d take over the farm one day,” the farmer explains.

“That’s just how it was – and that’s what happened with me. It happens gradually. There isn’t one day when your dad walks away and says ‘right son, it’s yours.’ You just do a little more over time until eventually it’s mainly you running it.”

Iain and his son James farm Kirkton of Monikie, near Dundee, a farm that’s been in the Fairlie family since at least 1900.

He was given the farm by a late uncle who didn’t have any family.

Iain and his brother David farmed Kirkton of Monikie and West Bamirmer on the coast between Carnoustie and Arbroath, until they split their partnership – very amicably, he stresses – two years ago, and now run one farm each.

Iain, 64, and James, 28, grow potatoes, winter wheat and spring barley on the arable farm. They’re not scared to move with the times either: “We’ve just put in an anaerobic digester plant, which generates 500KW of renewable electricity,” he says.

“It was James’s idea and it’s been his project entirely. He’s done everything from getting planning permission, finding a company we trust to install it, to getting it up and running.

“As a farmer it’s easy to say no to your son very often. Sometimes you have to say yes – and he’s done a fantastic job.”

Iain feels privileged his son has followed him into the business. “A lot of farmers’ sons don’t these days. James had lots of opportunities to do other things – he was at university and travelled in the southern hemisphere – but decided farming was what he wanted to do.”

Now Iain is passing on his knowledge that James may one day pass on to another generation. “My dad didn’t teach me everything – some things you have to learn on your own,” he said.

“He taught me enough. That’s how it’s passed down. I know no other way – there’s not a book for it.”