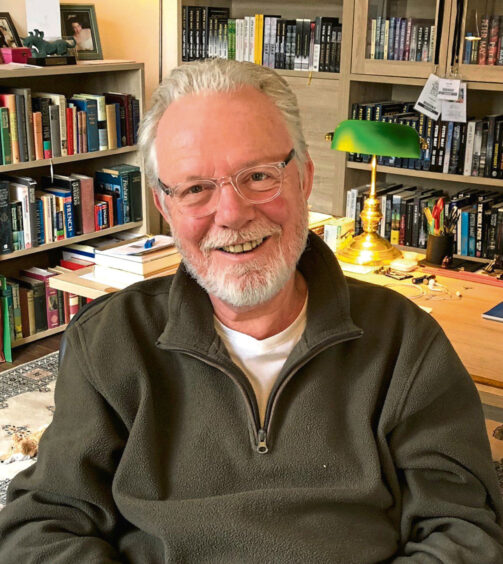

Internationally bestselling author Peter May was supposed to have called time on his writing career in order to focus on retirement and on his other passion, making music, by now.

Instead, he is back on the promotional juggernaut for his latest novel, A Winter Grave, a thriller set in a not-too-distant independent Scotland reeling from the effects of climate change.

The Glasgow-born writer started out working as a journalist before moving into television drama. Writing was always his first love though, and today Peter is best known for the Lewis Trilogy, the China Thrillers and, more recently, his eerily prescient detective novel, Lockdown.

Peter is chatting via video call from his home in the south-west of France, where he has lived since 2002. He and his wife, the playwright and screenwriter Janice Hally, are now naturalised French citizens. As we talk on a dark January morning, Peter tells me he certainly doesn’t miss the short Scottish winter days, but he remains firmly connected to his native Glasgow and Scotland, whether that might be as a vociferous campaigner against local library closures or choosing Glasgow and the west of Scotland as the setting for A Winter Grave.

Reading was a fundamental part of his childhood on Glasgow’s southside. “My dad was an English teacher and my mother was a rabid reader,” he says with a laugh, trying to find the right word to describe her incredible appetite for books. “She used to keep notebooks and she’d note down every book that she had read – she was always reading.

“We used to go to the library every Friday night as a family and came back with armfuls of books, and at secondary school I used to go to the school library and borrow books from them.

“Book were expensive, you couldn’t afford to buy books all the time so you borrowed them from the library.

“So in the last few months I have done a lot of tweeting and Facebook posting about library closures, particularly in the area I grew up in. At my old school they are even talking about doing away with the librarians and I get so mad at that!

“I mean, literacy is one of the pillars of civilisation and to damage the opportunity that young people have to read is seriously undermining our society.”

No clear path to authorhood

Peter’s dream was always to be an author but he says that option didn’t seem to be on the cards in his school days. “In the late 1960s there was no career path to becoming a writer,” he points out.

“I had never thought about being a journalist but I got a place on an NCTJ training course in Edinburgh, trained for a year and got a job on the Paisley Daily Express.”

Those years as a reporter have stood him in good stead. “There are fundamental things you learn: to write quickly, be economical with words, to research any subject without fear or favour and to pick up the phone and ask an expert,” he says.

“I write 3,000 words a day when I am working on a book and I’m usually finished a book in about seven weeks.”

The joy of research

Another reason for those words flowing so quickly is the meticulous research Peter is renowned for, which can take many months.

Once he has the material he needs, his approach to crafting his books is systematic.

“I do a very detailed synopsis, I do the drafting side of it when I am working on the synopsis,” he says. “Then when I’m finished it, I’m finished it – I don’t want to see it again, it’s on the spike!”

The research aspect is Peter’s favourite part of the process. “I generally enjoy it more than the writing,” he adds. Among the articles, books and documents he gets through, he says: “I usually manage to come across a book or two that really set my juices going, my imagination gets fired up.”

But perhaps most importantly, he adds: “Over the years I have made some fantastic friends through my research. When I was writing my China books all those years ago, there was a lot of autopsy stuff, I needed an expert and I needed advice.”

Contacts are key

He was lucky enough to encounter Steve Campman. Steve is now the medical examiner in San Diego and, according to Peter, “his experience is phenomenal. He was trained by the American Air Force – they were the pathologists for the FBI so he was doing all kind of weird stuff! He was great at giving me the detail I needed and he became a great friend.

“Writing can be a lonely experience, but when you are researching you are out there in the world. If I think of all the research trips I made to China over about seven years, I met so many people, made so many friends and saw such extraordinary things.”

Peter recalls his first attempts to meet with the Chinese police, which didn’t meet with much success. Then he met an American criminologist who had spent time in Shanghai, “training the top 500 Chinese police officers in the latest Western policing techniques”.

“He was really in with the Chinese police,” says Peter. “It was like getting an introduction to the mafia from a made man! When I first went I was met at the airport by the police, which was a bit alarming. They just whisked me off to my hotel and then took me to the police university.”

Climate change

A Winter Grave isn’t the first time Peter has looked at the impacts of climate change in his writing, “I have always been interested in the environment and the planet and what we are doing to it,” he says “I wrote Coffin Road (2006) about the disappearance of the bees – at that point I am thinking this is a serious problem, and I want to write about it but how do you engage people?”

He chose to write about it in the context of a thriller and that’s the same approach he has taken with A Winter Grave.

“Effectively I had retired,” he says. “I had turned down future contracts from my publisher. I had been doing a book or two books a year for 20 years or more and travelling, all over Europe and all over North America.

“It’s exhausting, all my contemporaries were retiring so I thought, why can’t I retire? I wanted to read for pleasure and to get involved in music, which is the other big thing in my life.

“So I had no intention of writing A Winter Grave. It was only because I had read a synopsis of the IPCC’s latest report and it was chilling and unequivocal – something has to be done this decade. COP26 was coming along and this was the chance to do this and I followed what happened there very carefully.”

Dismayed

The outcome of COP26 left him dismayed. “I thought ‘these people all know what the situation is, but there are more fossil fuel lobbyists at these COP conferences than there are representatives from the developing world’. The fossil fuel industry has spent decades spreading disinformation and scepticism.

“They used the same tactics as the big tobacco companies before them,” he says, incredulous. “They even used the same PR companies. I was just beilin’!

“The climate crisis goes down and down and down the agenda so that it barely gets a mention – and yet it is the single most important thing facing the human race.

“At the end of it, I thought I have got to write about this, and the problem was how. I don’t want to preach to people so I decided so I would write a conventional thriller and set it 30 years in the future and the world would just be changed by the climate crisis.”

Time hop

Setting some of the action in the near future was deliberate: “Thirty years is nothing at all. Thirty years back, we were just starting production of (Gaelic language drama) Machair and that just seems like yesterday.”

In A Winter Grave, the reader meets protagonist Cameron Brodie at two stages in his life: his early career, set in 2023, and a murder investigation in 2051, where he travels to a snow and ice-covered Kinlochleven to face the ghosts of his past.

Unusually for the painstaking researcher, Covid travel restrictions meant Peter wasn’t able to get to Scotland.

One of the most striking scenarios in the book is a flight taken by Brodie in an eVTOL (electrical vertical take-off and landing vehicle) air taxi from Glasgow to Kinlochleven via Mull.

“I had been to Kinlochleven before but it’s hard to write about a place at a distance when you are looking for specific detail,” he adds. “I contacted a friend of mine, Mo Thomson, who does a lot of drone photography and I asked him to go to Kinlochleven for me to take photographs and film and take drone footage of all the things that I wanted more detail on.

“He also programmed a flight simulator with the flight from Helensburgh to Mull and back inland up through Glencoe to Kinlochleven and he even programmed it to be a drone making the flight. You can programme in the weather conditions. We did the virtual flight and I was astonished to see how realistic it was. I watched it on a VR headset and it was just like making the flight. It was amazing, absolutely amazing.”

In the novel, as in real life, technology forms an integral part of everything his characters do (or try to do). But as Peter says, “All our technology is reliant on power – take away the power and we are almost back in the stone age, I wanted to make that point in the book.”

Music release

While Peter hasn’t quite managed to make good his escape from his writing career, he is excited that he has been able to find the time to release a song about the climate crisis to coincide with the publication of A Winter Grave’s.

Don’t Burn the World was written by Peter and Irish lyricist and poet Dennis McCoy. It is intended to be an anthem for the youth of the world and a plea for action in the face of the climate crisis. It is performed by the Peter May Band and was recorded at his home studio in France.

The chorus is sung by a children’s choir from the Isle of Lewis, adding resonance to the song’s message of protecting the planet for future generations.

Peter is determined to do his bit to halt the climate crisis, and says modestly: “I thought well, I have got perhaps a little louder voice than some people. The only thing I can do is make that noise heard above the roar of denial.”

A Winter Grave by Peter May is published by riverrun and priced £22.

Catch Peter in person at the following events:

Booksigning at Waterstones in Dundee on January 26, from 12-1pm,

An Evening with Peter May, St John’s Kirk, Perth, January 25

Peter May on A Winter Grave, Topping & Co, St Andrews, January 26

Conversation