The school holidays saw the family and I take a trip north up the A9 to Aviemore.

It always has been and still is one of our favourite spots in the country, full of happy holiday memories of cycling, walking and playing on the waters of Loch Morlich, surrounded by the most beautiful of Scottish Highland scenery.

For someone like me who needs to have a daily dose of plants, it’s a wonderland. Every time I go here I cant help but marvel at the beautiful old pines with their scaled bark a reddish colour, the way they are shaped, looking more like giant bonsai than pine.

The Scots Pine is one of our three native conifers, the others being yew and juniper, and it can live up to 700 years.

The best specimen I’ve seen grows in a wood just up from my house. It’s known as ‘The King of the Forest’ with a girth of over six metres, and is regarded as an outstanding example of Scotland’s native pine.

During my time working in the alpine department of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, we would make an annual trip to the Cairngorm mountains to tend a small outstation they have there.

Despite my eye being drawn to the those trees in the forest, it was a select group of alpines growing above the tree line we were heading there to attend.

Alpine aliens are something to behold

Alpines are mountain plants, and although the amazing rock garden and alpine house environments they have created at RBGE over the years do their best to replicate correctly the conditions they require to grow, the warmer temperatures of the city are never the same as those at the mountain ranges of the Alps or Himalayas.

For that reason, a select few are cultivated in the more hostile environment of the Scottish Highlands.

The plants that were chosen for the mountain site had to be carefully selected so that there was no risk that they could escape.

I’m not meaning that we would cage them in or tie them down but we couldn’t have them enjoying the conditions there so much that their seed could be blown out into the wider mountainside where they could grow unchecked.

There are plenty of examples where alien species have been brought in to the country from around the world via various plant hunters that have now become invasive species, taking over the environments where own plants should be growing.

Rhododendron – a colourful invasion?

Possibly the most notable example is the purple flowering rhododendron ponticum.

Introduced into Britain from the wild to be a garden plant in the 1700s, it found itself enjoying our Scottish hospitality so much it now dominates parts of our landscape, forming dense thickets outcompeting our own native plants.

Over recent years there has been a school of thought, particularly with woodlands, on planting more native species to benefit our wildlife, helping a partnership that has evolved together over time.

This thought is creeping into our gardens where we now comfortably leave patches of grass uncut, plant up with wildflowers and harbour a more relaxed attitudes to weeds.

On paper this all makes logical sense to me and as someone who wants to do what is right, this was a thought I was fully behind.

However as a lover of plants, I’ve always had a bit of a conflicting battle with this as I knew I was restricting myself to a limited garden plant palette.

Could I have a garden without lilies, a handkerchief tree, Himalayan poppies or red hot pokers? I doubt so.

Plus, I don’t think we really know how our natives are going to cope with climate change so who knows, maybe a tropical orchid today could be the food and shelter required for our pollinators, birds and other insects tomorrow.

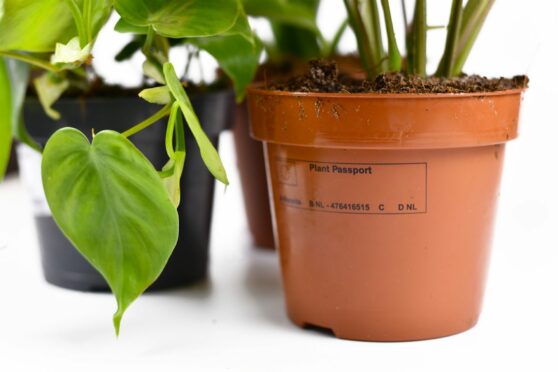

Plant passports please

Hopefully I’m exaggerating here but I do believe for these reasons we should be growing a wide variety of plants in our gardens; we just need to ensure we have the balance correct of exotics and natives.

Yet there is no doubt us gardeners have created problems for ourselves.

In one case, every year we are seeing less and less of our native ash tree in our landscapes. Ir is being killed off by a disease called ash dieback, first brought to Europe through the movement of plants.

There are plenty other pests and diseases that have arrived in our British shores like this.

Thankfully there are more tighter health procedures in place these days.

You may be amused at a plant having a passport – the label that can now be seen on the side of pots – but codes represent the locations they have been moved to during their lifetimes from their propagation stage through to the point of sale, so any notifiable pest or disease can be traced back down the chain.

One thing is gardeners can do to help is not sneak cuttings back into the country from plants we like from our holidays abroad, as you never know what else you could be bringing in to our country with it.