Forensic artist Dr Chris Rynn’s striking facial reconstruction of a woman murdered, bundled into a wheelie bin, encased in concrete and dumped in a river in Amsterdam, is already yielding new leads.

It was a summer’s day in 1999 when firefighter Jan Meijer noticed a wheelie bin bobbing up and down on the River Gaasp near his home in Amsterdam.

Heading out to retrieve it in his boat, he noticed something strange.

The bin was nailed shut, heavier than he expected, and it smelled gut-wrenchingly awful. He towed it to shore and rang the police.

When officers prised the bin open, they found bags of washing powder piled on top of concrete.

And when they turned the bin upside down, a woman’s body fell out.

Murdered and dumped

The investigation at the time revealed she had been shot in the head and chest, stuffed into the wheelie bin, encased in concrete, and dumped in the river.

It was deduced she was probably in her mid-20s and “partly western European and partly Asian”.

However, more recent forensic investigation has narrowed down her place of birth to either the Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg or Belgium.

While she was wearing a gold-coloured watch on her right wrist, a snakeskin print bag was also found in the bin.

Men’s clothing, believed to belong to the killer, including a jacket with a red circular symbol, was also stuffed in beside her.

Identity a mystery

Despite Dutch detectives’ efforts, her identity has remained a mystery, and no suspect has ever been questioned in connection with her death.

Now, Dr Chris Rynn, a freelance forensic artist living in Highland Perthshire, has offered fresh hope that her story might be uncovered, and her identity revealed.

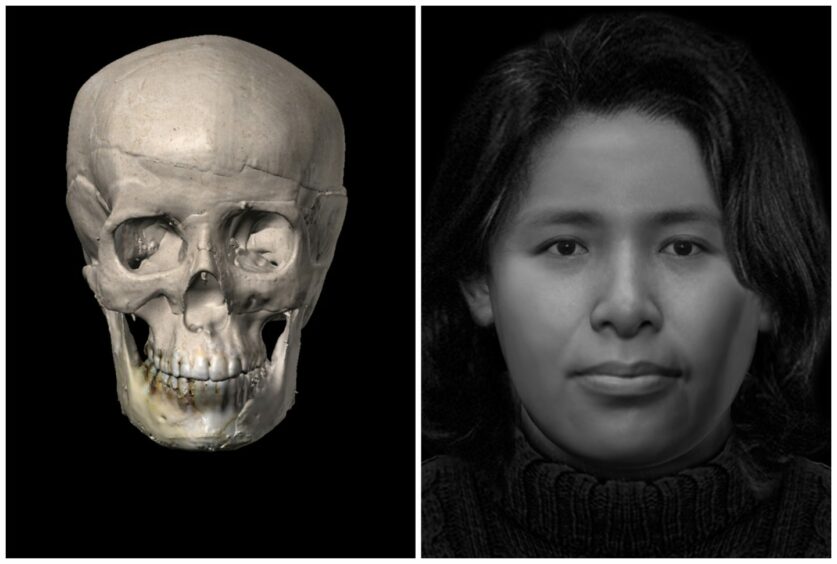

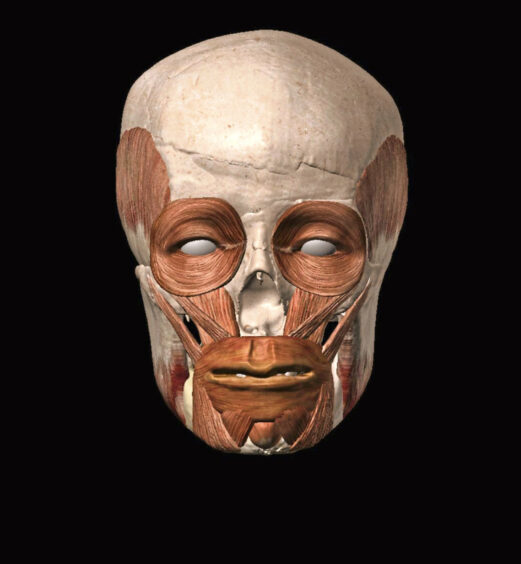

Combining his medical artist’s skills and anatomical expertise in the human skull with scientific analysis and state-of-the-art digital technology, Chris has given the ‘woman in the bin’ a face.

Striking facial reconstruction

His striking new facial reconstruction forms a collection of images used by global policing agency Interpol for a campaign aimed at identifying 22 women.

They are all believed to have been murdered in Belgium, Germany and The Netherlands, aged between 15 and 30. Their bodies were discovered between 1979 and 2019.

In a new push to identify them, Interpol has published a ‘black notice’ for each woman, normally only circulated among police.

Details of each case, new facial reconstructions, photos and details of where they found, their injuries, jewellery and belongings, have been gathered into Operation Identify Me which hopes to trigger someone to come forward.

200 tip-offs

Incredibly, after years of silence, police have already received more than 200 tip-offs, including potential names of victims, with 122 in Germany, 55 in Belgium, and 51 in the Netherlands.

Chris’s lifelike digital image of the ‘woman in the bin’ is worlds away from the basic clay model produced back in the 90s.

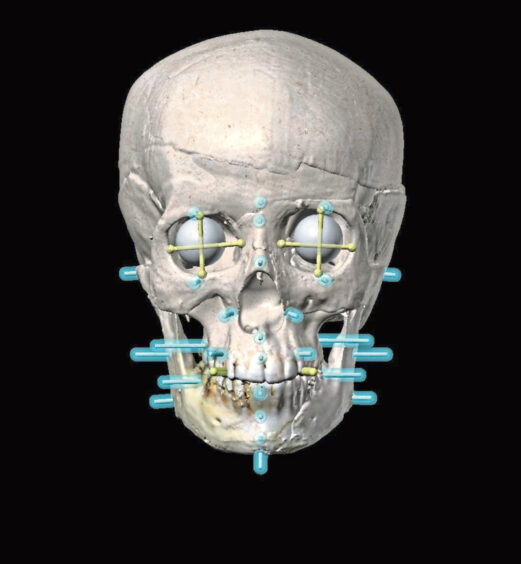

Using specialist software, including a haptic 3D modelling device, he gradually pieced her together, layering muscle and soft tissue over bone, and using equations to determine the shape of her nose, eyes, and mouth.

Skull smashed

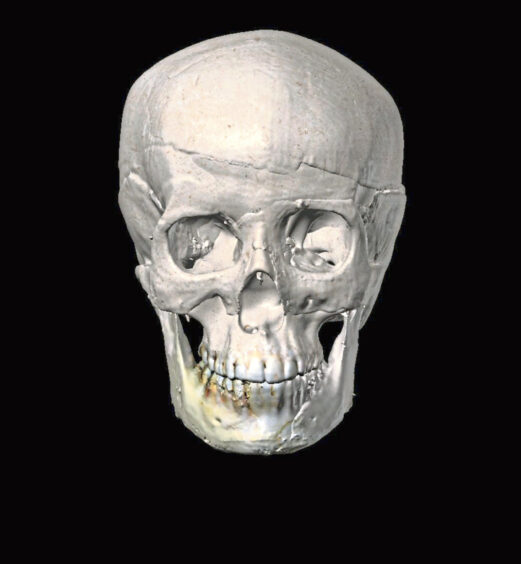

It wasn’t easy – the woman’s skull had been smashed to pieces.

“They photographed it before it fell apart, then CT scanned the pieces and teeth,” explains Chris.

“I had to reassemble it like a jigsaw, and put the teeth back in.

“When I started sculpting the face, I could see it was clearly female, but not European looking – it was more South East Asian.”

Chris describes his work as “like doing a portrait of someone who’s not there”.

And he says he never knows how a face is going to look until he has reconstructed it. “I can’t see a face; I have to build it,” he adds.

When he was sent the post-mortem photos and graphic images of her remains, he realised there was something familiar – he recognised them from when he was a student in Manchester 20 years ago.

Familiar face

“I remember my PhD supervisor had the photos,” he recalls. “The case had come to the department and we had a look at them. I’d done my anatomy degree and was doing medical art training and facial reconstruction.

“We were trying to get more accurate and figure out where the gaps were so we could make better images.

“The story about the woman being murdered and dumped in a wheelie bin haunted me. I never forgot.”

His PhD supervisor had also made a basic clay sculpture of the woman’s face back in the 90s, but Chris had never seen it. And he deliberately avoided looking at it, fearing it might bias his 2023 interpretation.

Cold cases

“I’d been working with the Netherlands Forensic Institute for years on cold cases and thought this was just another case,” he reflects.

“When I was told it was an old one from the 90s, I said, ‘don’t tell me anything, just show me the CT scan, skull and photos of her body after it was dragged from the river and don’t let me get biased about it.”

Other cases that form Operation Identify Me include a woman with a distinctive tattoo of a black flower with green leaves and “R’NICK” written underneath who was found lying against a grate in a river in Belgium in 1992, and a woman’s body found wrapped in a carpet and bound with string at a sailing club in Germany in 2002.

Harrowing cases

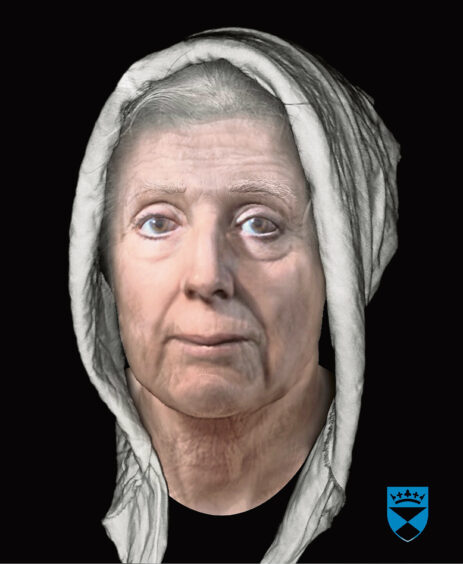

Chris’s skill at reconstructing the faces of the long dead spans harrowing forensic cases to work for heritage sites on a mission to bring historic figures “back to life”.

In some cases he adds video software that makes them “come to life”, with moving eyes and facial expressions.

One was Lilias Adie, an 18th Century ‘witch’ who died in jail before she could be burned for alleged crimes including having sex with the devil.

Her remains, buried under a stone in Torryburn in Fife, were exhumed in the 19th Century, and Chris used photos to build her image.

More recently, he created images of characters linked to Whithorn Abbey, including a medieval woman buried in the grounds and 13th Century Bishop Walter.

His current caseload is a mix of police and museum work, including the visualisation of an ancient Egyptian Priestess, a Pictish Scot and four medieval skulls held by Perth Museum.

Traumatising work

Some of Chris’s most traumatising work – work that has left him suffering from severe PTSD – has included identifying perpetrators of child abuse.

Having completed his PhD at the University of Dundee in 2006, Chris worked there until 2020, running the Forensic Art MSc.

He also worked alongside world-renowned forensic anthropologist Professor Dame Sue Black at the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification.

A ‘last resort’

He regards his work as “a last resort”, but says if his facial reconstructions do yield new leads, then it could help an investigation.

Meanwhile, in a cemetery in Amsterdam, a grave is marked by a plaque that reads “unidentified deceased” – the woman in the bin.

Wouldn’t it be incredible if her identity was revealed.

Conversation