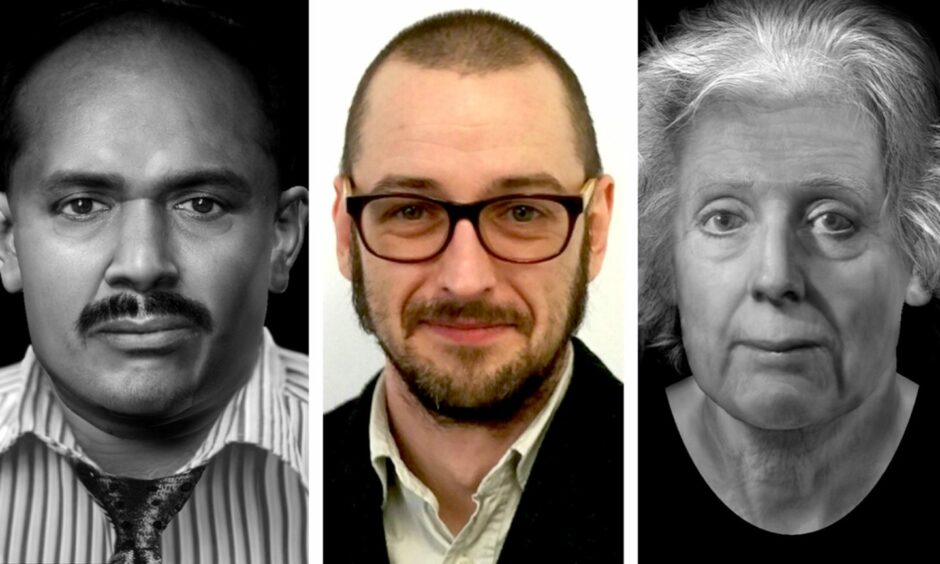

Forensic artist Dr Chris Rynn reconstructs the faces of murder victims and helps to identify killers and child abusers. But there’s a price to pay – he’s suffered from severe PTSD and faced murder threats.

From studying skulls and the remains of dismembered bodies to investigating child abuse cases, there’s no question that Dr Chris Rynn’s work is harrowing. It would traumatise even the most hard-hearted of individuals.

The Perthshire-based forensic artist recently hit the headlines when it was revealed that his new facial reconstruction of a woman who was murdered, bundled into a wheelie bin, encased in concrete and dumped in a river in Amsterdam in 1999 is already uncovering new leads.

Using specialist software, Chris gradually pieced the ‘woman in the bin’ together, layering muscle and soft tissue over bone, and using equations to determine the shape of her nose, eyes, and mouth.

It wasn’t an easy job – her skull had been completely smashed to pieces. Chris had to reassemble it like a jigsaw and put the teeth back in to create a striking lifelike digital image.

The investigation at the time revealed the woman had been shot in the head and chest, stuffed into the wheelie bin, encased in concrete, and dumped into the River Gaasp.

I was always into skulls, even as a kid.”

DR CHRIS RYNN

Chris’s striking new facial reconstruction forms a collection of images used by Interpol for a campaign aimed at identifying 22 murdered women – including the ‘woman in the bin’.

Incredibly, after years of silence, police have already received more than 200 tip-offs, including potential names of victims.

Bringing the dead back to life

Chris’s skill at reconstructing the faces of the long dead spans harrowing forensic cases to work for museums and heritage sites on a mission to bring historic figures “back to life”.

In some cases he adds video software that makes them “come to life”, with moving eyes and facial expressions.

Traumatising work

Some of Chris’s most traumatising work – work that has left him suffering from severe PTSD – has included identifying perpetrators of child abuse.

So how he did he get into this arguably disturbing line of work?

He laughs: “I was always into skulls, even as a kid, brought up in Wigan. We had a cat who used to bring in dead birds and rodents. I’d de-flesh them and keep the skeletons.

“I was really into nature, and death’s a big part of nature. I was just a creepy kid I guess.”

His mum was a nurse, so there were medical encyclopaedias all over the house which he leafed through with great enthusiasm.

“There were these amazing picture books where you could flip the page and see all these transparencies, so there’d be flesh, then you’d peel it back and see muscle underneath, then bone,” he says.

“I loved that stuff when I was about five or six. My parents started buying Enid Blyton and Terry Pratchett books for me instead!”

Dead human bodies

His first brush with dead human bodies came early, too, when he was around five years old.

His grandmother died, and, as is the Irish Catholic tradition, family members were encouraged to view the open casket.

A few years later, as an eight year old altar boy, Chris was shown inside the furnace of the crematorium after a funeral service.

“Death is the only thing we’ve all got in common,” he muses. “It’s the only mystery left.

“We don’t know what happens after death, and we never will, and that intrigues me.

“My dad died when I was 20, my brother died of cancer 10 years ago, and my mum died in the first wave of Covid, along with her entire care home.”

Scarred

Not being allowed to see her dead body or bury her clearly scarred him.

“I’ve seen thousands of dead bodies but I wasn’t allowed to see my mum’s dead body,” he laments.

“It made me really realise how important it is to get emotional closure. And I think that’s what really drives me to do this work.”

Working with Professor Dame Sue Black

Having completed his PhD at the University of Dundee in 2006, Chris worked there until 2020, running the Forensic Art MSc.

He also worked alongside world-renowned forensic anthropologist Professor Dame Sue Black at the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification.

Some of this work involved investigating child abusers. It left Chris reeling. He suffered from severe PTSD as a result of poring through traumatic images and had no choice but to take time off work.

Death threats

Chris is conscious not to reveal his exact location in ‘Highland Perthshire’, fearing retribution.

He explains: “When you identify dead bodies and murder victims for 20 years, and put paedophiles in prison, you don’t know who’s after you.

“When you get death threats from a murderer, you know they’re for real. So I don’t want people to know where I live anymore.”

A ‘last resort’

He regards his work as “a last resort”, but says if his facial reconstructions do yield new leads, then it could help an investigation.

“When a dead body is found, there are four primary identifiers – DNA, dental records, fingerprints and X-rays. But if you’ve never been arrested, your fingerprints aren’t going to be on a database.

“If there’s nothing to go on, the body’s left in the fridge and it’s a dead end; there’s no investigative leads. So by putting a face together as accurately as possible, someone might recognise it and provide a toothbrush with DNA on it.”

In some cases, thanks to Chris, murder victims have been identified, including a Lithuanian man murdered in Thames Valley.

His dry skeleton was found, and all his clothes had deteriorated. A label at the back of the neck revealed his top had been made in Lithuania, so when Chris put his reconstructed face out in Lithuania, he was recognised as a missing person.

“His mum had reported him missing and given a cheek swab, but sadly died before we got the ID.

“We know who he is but we still don’t know who killed him and why. This happened in 2015, so have they killed anyone else? It sometimes opens up a whole can of worms.”

Dumped in a canal

In another Dutch case, Chris’s reconstruction of a Polish man’s face was circulated in Poland. His sister recognised it.

“He’d been shot multiple times and dumped in the canal. The question is – who killed him?”

Dismembered

In another harrowing case, Chris reconstructed the face of a man violently murdered in London. His skeleton was found in a back garden in Wimbledon by builders in 2022.

His body had been dismembered.

Carbon dating concluded the skeleton was from the 1960s.

The case has featured on Crimewatch.

Body in a barn

Chris also produced a facial reconstruction of a body found in a barn in Micheldever, Hampshire, in 2018.

“Three witnesses recognised him but wanted to see him without the hat and glasses found at the scene, so I took them off and put the hairstyle on that they all described, and we put out the second version last year,” he says.

“There have been a few calls, so missing person photos are coming in, and I’m doing craniofacial superimposition – to compare the 3D skull to the missing person photos.

“It then goes to be DNA matched in a lab, and we wait, and wait.”

Historic cases

Another facial reconstruction Chris worked on was that of Lilias Adie, an 18th Century ‘witch’ who died in jail before she could be burned for alleged crimes including having sex with the devil.

Her remains, buried under a stone in Torryburn in Fife, were exhumed in the 19th Century, and Chris used photos to build her image.

More recently, he created images of characters linked to Whithorn Abbey, including a medieval woman buried in the grounds and 13th Century Bishop Walter.

His current caseload is a mix of police and museum work, including the visualisation of an ancient Egyptian Priestess, a Pictish Scot and four medieval skulls held by Perth Museum.

Conversation