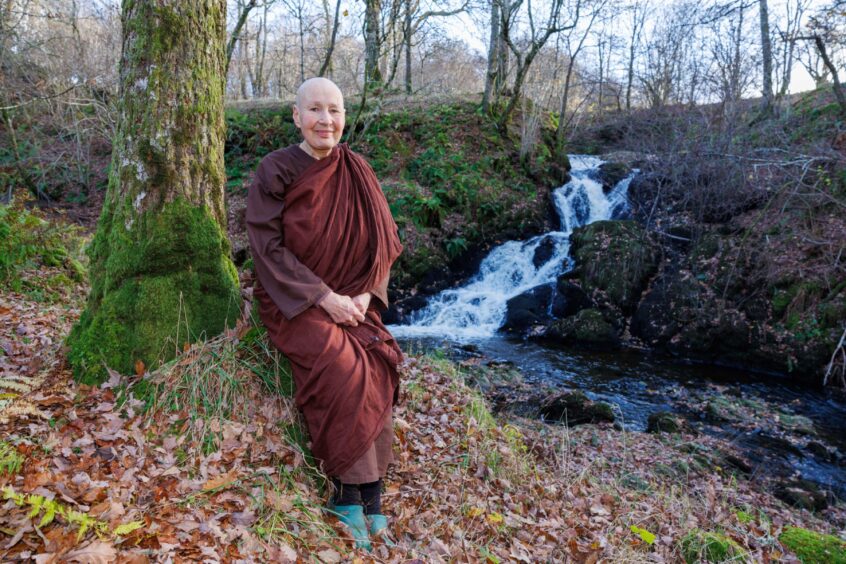

As she wanders serenely through the forest in her brown robes, simple sandals, and sporting a shaven head, she cuts a striking figure.

Sister Ajanh Candasiri is a Buddhist nun based at Milntuim Hermitage near Comrie, and her life is devoted to the disciplines of meditation, study and service.

There’s no place for the distractions of TV, radio, music, or newspapers in the 76-year-old’s world.

She lives by the Theravada school of Buddhism, specifically the Thai Forest tradition, which centres on self-restraint and abstention from all forms of indulgence – it pretty much rules out celebrating Christmas.

A typical day sees Sister Candarisi rising at 4am, meditating, chanting, eating a simple meal, working in and around the hermitage, whether on administrative duties, gardening or maintenance, writing (she’s written several books), and then doing a little more meditation. She fasts frequently, and she’s expected to forgo food from noon until sunrise the following day.

Frugal lifestyle of a Buddhist nun

Her frugal lifestyle is a far cry from what most people in modern society experience – especially at this time of year.

Christmas, for the majority, tends to be a time of vast gluttony, spending money like water, and exchanging gifts galore.

It can also be a time of stress, panic and burnout. The commercialism of Christmas is inescapable, with in-our-face adverts insisting we must buy this perfume or that aftershave, or how about a new sofa.

Sister Candasiri, meanwhile, lets it all wash over her. She’s not exposed to the madness – she chooses not to be.

Here in Glenartney, three miles from Comrie, she can be deep in quiet contemplation as she strolls through the sanctuary’s 13 acres of woodland, pausing to listen to birds in the trees, and gazing in awe at rivers and crashing waterfalls.

It’s a largely solitary existence, and one that can see her retreating to a hut in the forest for three weeks at a time.

Meditation at Cultybraggan

I meet Sister Candasiri as she’s preparing to take a drop-in meditation in the chapel at nearby Cultybraggan Camp. She has such kind eyes, such a look of compassion. I feel as though I am being cocooned and cared for, simply by being in her calming presence.

It’s cold inside the chapel – it’s a basic, no-frills corrugated iron Nissen hut – but rugs are available if you’re extra chilly.

I wrap my scarf tightly around me, perch on the plastic seat and watch as Sister Candasiri lights a candle. I close my eyes and allow her soft voice to wash over me.

I’d come here tense, anxious and stressed, but as the hour passes, I find myself becoming settled and relaxed. Her main message seems to be – take time out for yourself, think kindly of others, and of the many people suffering across the globe.

We finish up with steaming cups of peppermint tea, before heading to the hermitage for a chat.

Nuns’ hermitage

Sitting in the ‘shrine room’, which is dominated by a huge marble Buddha, Sister Candasiri tells me that Milntuim was purchased as a nuns’ hermitage in 2011, using money her parents left when they died.

Since then, she’s welcomed nuns and ‘anagarikas’ (students) and lay friends to spend time here.

So, Christmas. How will that pan out, I wonder?

“It’ll be rather a quiet time,” she muses. “It’s a nice time to do a lot of meditation. To contemplate the difficult things that so many people are dealing with.

“To send out thoughts of good will and support the world in that way. It’s a time for quiet contemplation and the equivalent of prayer. If the weather is nice I may go for a walk.”

A quiet time at Christmas

I take it there won’t be a Christmas tree festooned with decorations? She shakes her head. “I often receive cards so they get hung up, but I don’t go overboard with decorations.”

A lavish turkey dinner won’t feature, either. Instead, Sister Candasiri will see if any friends visit, and whether they’ve brought anything special to share.

“Otherwise, it’ll be a simple meal that will, hopefully, fill our stomachs and nourish the body – and not give us indigestion!” she smiles.

It wasn’t always this way for Sister Candasiri. Born in Edinburgh in 1947, she was brought up Christian – and Christmas was a big deal when she was growing up.

Journey to becoming a Buddhist nun

She became a nun in 1979, aged 31. “You want to know how I landed up here?” she smiles. Yes, of course!

“I suppose I wanted to be good,” she reflects. “When I was about 14, I was a very devout Christian.

“I wanted my life to be dedicated in some way to service, or doing something to make the world a better place. It was all thought of in terms of God. But I went through a rebellious phase in my teens and I wasn’t interested in practicing religion at university.

“When I left, I realised I still had the sense of wanting to be good, kind, loving, generous, relaxed, peaceful and all the rest but I didn’t know how to do it.”

After graduating, she worked as an occupational therapist and lived a “pretty normal life” – with friends, boyfriends, and an income.

But it wasn’t enough – it didn’t sustain her – and even after exploring other religions, she struggled to be at peace with herself. She often found herself battling with feelings of insecurity, anxiety and jealousy.

“Jealousy was a big thing – it was like an illness,” she admits. “I was jealous of my best friend for a while, and jealous of my boyfriend. There was nobody I could talk to about it. And so I began meditation.”

Enjoying the monastic life

She first did this with a Sufi group, who practiced a mystical form of Islam, and then joined a couple of retreats in Christian monasteries. She was also part of a Kabbala group.

“I enjoyed the monastic life, giving up worldly pursuits to devote myself to spiritual work. But I never thought I’d be a nun,” she says.

That changed when she met American Buddhist monk Ajahn Sumedho in 1977. He was one of the most senior Western representatives of the Thai Forest Tradition of Theraveda Buddhism, and later became Sister Candasiri’s teacher.

“The monks lived close by and I went along to their evening meditations and prepared food to offer from time to time,” she recalls.

“They looked completely different, with ochre robes and shaven heads. It all seemed very foreign in one way, and yet, I’d never heard such good sense.

“After 18 months I went on retreat. This gave me a deeper understanding of Buddhism – and I saw that if I practiced, I didn’t need to suffer. Until then it all seemed rather hopeless.”

Opportunities for women to become nuns

During that first retreat, there was talk of creating opportunities for women to become nuns, and Sister Candasiri was keen to become part of the community at Chithurst Buddhist Monastery in West Sussex.

“It was a lightbulb moment,” she reflects. “Before then I had a pleasant life. I went to meditation groups, I had friends, an interesting job and plenty of money. I had everything most people would want, but the possibility of being able to do this 100% was extremely attractive.

“I realised if I really wanted to help people, I had to help myself. I found that if I applied the teachings I was hearing, I’d be able to share something of value.”

For her family, however, becoming a nun was “absolutely devastating”,” she laments. “I knew they wouldn’t like it, that it would be a disappointment. They were hoping I’d marry and have children. But I knew I had to follow this path.”

Her first step was to move into the monastery at Chithurst, which at that time was little more than a dilapidated Victorian mansion.

‘We were allowed to have our heads shaved’

The nuns – and there were only four – wore white robes to start with, and had their hair cropped.

“I think Ajahn Sumedho thought shaven headed women was too weird!” she smiles. “But after a few months, we were allowed to have our heads shaved.

“Why was that? There’s less to be concerned about. It’s an obvious step away from trying to make yourself attractive. It’s a well-known sign of a religious person, somebody who has devoted themselves to spiritual pursuits rather than finding a partner, having children, those things.”

As the nuns’ group expanded at Chithurst, they needed to move to a bigger site – somewhere with more facilities for larger gatherings. So Amaravati, a Theravada Buddhist monastery, was founded in Hertfordshire in 1984.

Around 2007, Sister Candasiri began thinking about founding somewhere smaller that would be a single community just for nuns.

She moved into Milntuim in 2011, although she continued to visit Amaravati regularly.

The former resident, Bob Fryer, was, she says, “very sympathetic” to Buddhist principles, rejecting a higher bid on the property.

Focus on contemplative practice

How many people live here now, I ask? She laughs. “Mostly it’s just me, although the idea is to create a nuns’ monastery here. A place that’s a little bit quieter, a little bit less going on, where we can have more focus on contemplative practice, and where, as a senior nun I decide things.”

Is there anything she misses from her old life? What about boyfriends, or maybe music?

“Early on, I missed having my own way!” she declares. “I remember going to Thailand and looking at the nuns. They all had exactly the same robes, shaven heads, they walked in line, they all bowed together. I thought, ‘oh my goodness, I’m going to just have to be another nun’. The idea of fitting in was quite difficult.

“And having had ‘traditional’ relationships such as boyfriends, I’m glad to not be in that kind of relationship. There can be pain and hurt in any kind of relationship – that’s part of being human!

“Our practice is to understand how and why we are vulnerable in that way and how to live, and love, in a way where there is less attachment and therefore less pain.”

While she misses music, if she hears it these days, it stays with her for weeks after and can become “quite tedious”.

Free from consumerism

Does she ever get lonely or bored? “Sometimes, but very rarely,” she muses. “I enjoy being alone.”

In being free from the trappings of consumerism, the vanities of appearance and attachment, which she regards as causes of suffering, Sister Candasiri feels greatly liberated.

“It’s not a flashy life. It’s probably seems utterly weird! But I enjoy it,” she elaborates.

“Materialism is tragic and not sustaining. If you’re always hankering for this and that, you’re never satisfied. You always have to have more. And that can be a tragic cost to people’s happiness.”

Cultivating a heart of generosity

So what IS important to Sister Candasiri? “The word that comes to me is ‘friendliness’,” she muses. “Can you be friendly with yourself? Do you respect and like yourself?

“I think quite a lot of people don’t. When you can like yourself and be at ease with yourself, it’s much easier to like and be at ease with other people. Cultivating a heart of generosity, of good will, forgiveness, understanding – these are beautiful qualities.

“The sad thing is that some people don’t want to look at themselves too closely because they’re scared of what they might find. Yes, there might be some pretty unpleasant stuff in there, but you’re not going to get rid of it by running away from it, or trying to bury it more deeply. You get rid of it through contemplation and by understanding the nature of these things.”

“It’s not a flashy life. It’s probably seems utterly weird! But I enjoy it.”

SISTER CANDASIRI

So while there’s a strong sense of freedom in not having to conform with society, being a nun carries many restrictions, says Sister Candasiri, “in the sense of rules and ethical guidelines that govern how we relate with people, where we go, what we do or don’t do and so on, but that leads to a tremendous inner freedom and peace. That’s why we do it!”

Ultimately, Sister Candasiri, who admits her lifestyle is “very strange and wonderful”, hopes to send messages of good-will to people across the world over the festive period and beyond.

Sense of gladness

“It’s about thinking kind thoughts, wishing people well, wishing them happiness,” she muses.

“There’s a wonderful feeling that comes with having done something good and generous – there’s a sense of gladness.”

She recalls the times she did alms rounds in Comrie, admitting she felt strange making herself dependent on other people as she stood with her bowl in the freezing rain.

It’s not about begging for donations, she reiterates. “There are no expectations that people will give. For me it’s an inner process.

“You reflect on the fact that most people in the world don’t have enough to eat. Many don’t have a place to live. It’s quite humbling. You realise we don’t need half as much food as we think we need.

“But it’s also giving people an opportunity to do something that’ll make them happy and feel good about themselves, should they offer.”

Cultivate a sense of contentment

As my stomach rumbles, I try not to think about the lavish Christmas I’m planning, and the new jacket I’ve ordered online. Do I really need it? I’ve already got way too many cluttering my wardrobe. And – am I actually hungry?

“I used to have so many clothes, too,” says Sister Candasiri, as if in empathy. “Now I’ve got robes, a skirt, a jacket – you don’t have to have half a dozen of everything.

“A lot of these extra things are bound up with how we see ourselves, and that creates so much suffering. It’s much better to cultivate a sense of contentment, considering: ‘I’ve got something to wear and it’s enough’.”

The subject of death for a Buddhist nun

Before I leave, there’s one more subject that rears its ugly head. Death. How does she feel about that?

“It’s inevitable; it’s the one certainty,” she reasons. “But the encouragement is to live carefully and responsibly so that you don’t have to suffer fear and remorse.

“If you’re selfish and hurt people, this will stay with you. If you’re good and kind then you’ll hopefully end up somewhere less unpleasant.

“We’re encouraged to think about death a lot. I find it helps me to value the opportunities and the life I have, and to make the best of it. It’s about being present, living fully in each moment.”

- For more details on Milntuim Hermitage, see amaravati.org/milntuim-hermitage/

Conversation