It’s believed to be the oldest tree in Britain – but the Fortingall Yew in Perthshire is fighting for survival.

I was shocked to hear predictions that the age-defying wonder, believed to be between 2,000 and 5,000 years old, may not live to see the turn of the next century.

The trouble, largely, is that it attracts the attention of souvenir hunters. And, I must admit, I thought twice about even writing about it.

God forbid anyone hacks down the tree (think Sycamore Gap), or carves off a chunk of it, because I’ve drawn attention to it.

And yet I feel this amazing survivor should be celebrated, gazed at, and indeed written about.

It can be found in a corner of remote Fortingall churchyard in Glen Lyon, standing next to the 18th Century church.

It’s not easy that easy to photograph but I gave it a bash on a recent visit.

Mysterious roots

It’s no surprise to discover the tree is shrouded in mystery.

One story suggests it was the birthplace of Pontius Pilate, who ordered the crucifixion of Jesus!

Another local anecdote says that the Roman governor was born in the village of Fortingall and played under the yew as a child.

While seemingly far-fetched, these theories are not impossible.

The Scottish origins of Pilate are far from clear but it is said he was born after envoys arrived from Rome to strike up diplomatic relations with Caledonian tribal leaders.

At the time, Metellanus, the 17th King of Scotland, held Dun Geal in Glen Lyon with claims a Roman fathered a child with a Caledonian woman during the visit.

The origins of the Fortingall Yew

So how did the Fortingall Yew come to be here in the first place?

It’s thought it was planted intentionally, with someone nourishing and caring for the seedling, ensuring that it thrived and survived.

The tree hit the headlines in 2015 when scientists from the Royal Botanic garden in Edinburgh speculated it was undergoing a “sex change” after it started sprouting berries on one of its upper branches – something only female trees do.

However, the lower parts of the tree are apparently male.

Despite having survived all these years, scientists monitoring the sprawling yew’s health claim it’s in danger of dying as a result of tourists tearing off parts of it as souvenirs.

Some have removed twigs and branches in their greed to take home a piece of the iconic tree, while others have climbed over its protective stone wall barrier to tie on beads and ribbons.

These actions have weakened the tree and left it in an increasingly poor condition.

Suffering at the hands of tourists

This vandalism, or, as some might like to think of it, careless enthusiasm, isn’t anything new.

The Fortingall Yew became such a popular tourist attraction in the 18th Century that even then, visitors were carving off bits of the tree.

And it wasn’t just tourists who contributed to this decay.

Local legend has it that parts of the trunk were used to make arrows and tools and claims Beltane fires were lit at the base of its trunk, causing it to split.

In 1769, it was supposedly possible to drive a coach and horses straight through the middle.

The tree has many trunks, but it’s much smaller in circumference than it was in its prime – and before it suffered as a result of souvenir seekers.

Look closely and you’ll see posts set into the ground inside the enclosure. These show the tree’s once massive girth, at around 16m.

Some predications say that the Fortingall Yew won’t live to see the turn of the next century at the current rate of damage. And that would be a huge shame.

So please, if you do pay it a visit, have some respect and admire it from behind the barrier.

Yew’s links to religion

There has been a church in the shadow of the great yew since the early 700s AD, although the current church was built between 1900 and 1902.

Because they live for such a long time, yew trees have been linked with the idea of immortality, and with death.

To the ancient Celts, the yew was a sacred tree that offered a defence against deadly curses, while the Romans believed that they grew in hell near the entrance to the underworld.

Beyond the tree, it’s well worth having a wander round the pretty churchyard.

The belfry of the old 18th Century church, added in 1768, can be seen in an enclosure.

Meanwhile, Rev Duncan Macara, who was the minister between 1754 and 1804, is buried beneath the tree.

In the unsettled period that followed the Jacobite uprising of 1745, Rev Macara brought peace and tranquillity to Fortingall parish, which included Rannoch and Glen Lyon.

He was responsible for the establishment of the first two schools in Glen Lyon, as well as two schools in Rannoch.

Site of Celtic monastery

While the first Christian church was built here long after the yew was planted, there was previously a Celtic monastery at the same spot, thought to have been established by Adomnan, Abbot of Iona from AD 679 to 704.

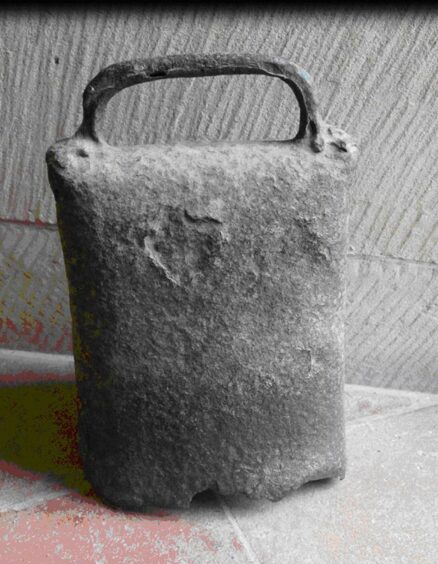

There’s no evidence of this monastery today, but an ancient hand bell dating to the 7th Century was kept inside the church for many years.

Sadly the bell was stolen from a locked metal cage in 2017 and its whereabouts remain a mystery.

Outside the church you’ll also find a worn stone font bowl, dated from the 8th Century, and several cross-marked slabs, with one thought to be 7th Century.

Inside are three fragments of Pictish cross-slabs dating to around 800 AD.

- Fortingall is eight miles west of Aberfeldy, at the eastern end of Glen Lyon.

- Gayle is pictured wearing a Munro Beanie to keep cosy.

Conversation