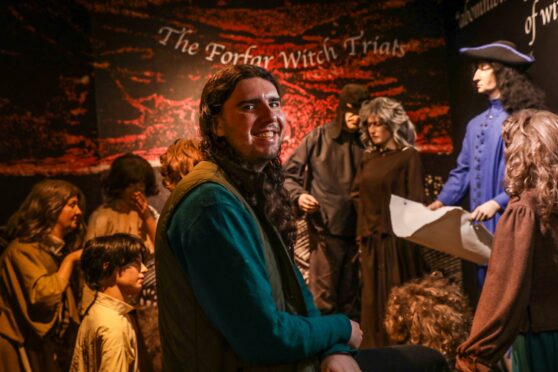

Shaun Wilson is a 27-year-old man living in Forfar in 2024, not a woman on trial for witchcraft in the 1600s.

But when he reads the stories of accused Angus ‘witches’ who were targeted during barbaric witch trials, he feels “a strong connection”.

Why?

“The people accused of witchcraft in Forfar in the 1600s were marked as different,” explains historian Shaun. “Whether that was because of their religion, their looks or their behaviour.

“I myself am autistic and dyslexic, and I have ADHD. And I can tell you that society is still not good with people who are different.”

Forfar man Shaun became interested in his hometown’s witch trials while studying history at Aberdeen University.

He felt a kinship with those accused, and soon began uncovering links between so-called “witchcraft” and autism.

“There is a clear link between the historic witch trials and disability. For example, accused people were very often blind,” explains Shaun, who works part-time as a visitor assistant at Forfar’s Meffan Museum.

“Because when you get cataracts, your eyes go white. Back then, there was the belief that that was a visual sign of the devil having corrupted your soul.

“But also – the town weirdo, the town recluse.

“These were the types of people being accused of witchcraft. And back then, people had no idea about neurodivergence or autism.”

Shaun recognised traits in Inverarity ‘witch’

And although he cannot say for certain – “after all, I wasn’t there” – Shaun believes that some of the area’s well-known ‘witches’ could well have been autistic, or otherwise developmentally different.

“One of them is Marjorie Ritchie, the accused ‘witch’ from Inverarity, just up the road,” he says.

“When you read her ‘confessions’, you get a little bit of insight into her. She seems to get really overwhelmed when people are confrontational to her.

“She has these kind of weird verbal outbursts. And she gets greatly annoyed with her neighbour’s behaviour and how he goes about his day.

“Also, she has these little rituals that she does, which are mentioned in the accusations and used to condemn her.”

Shaun explains that social overwhelm, verbal outbursts, repetitive motion (‘stimming’), a need for routine and black-and-white thinking are all common autistic traits.

“At school, I tapped my fingers a lot, moved around a lot, had outbursts,” he says. “I quickly learned in high school to hide that. I’m lucky – I was able to do that, somewhat.”

Accused child Joanet Huit was ‘strange’

Another accused “witch” who caught Shaun’s attention was a child named Joanet Huit.

“She’s described as very small, and not very able. Always very quiet and following close to her mother everywhere,” observes Shaun.

“She’s said to be a bit behind for her age, which is somewhere between 10 and 13, but described as a ‘pretty dancer’.

“Now, her mother Helen Guthrie was a well-known alcoholic. So it’s possible Joanet was born with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, which would explain her small stature.

“But either way, people are pointing out that she’s strange, she’s somehow different and acting in a way that’s not normal for a child.”

For Shaun, the sense of connection as an autistic person “comes with heartbreak”.

Because 400 years on from Scotland’s witch trials, while activists fight on to have those accused pardoned, autistic children are still facing spiritual persecution.

Modern ‘witch trials’ abusing autistic youth

“There’s a huge overlap today between mental illness, learning difficulties and modern witchcraft trials,” Shaun says solemnly.

He tells me of “megachurches” in the US which claim to “cast out” autism by likening it to a demonic possession.

And how violent “conversion therapy” methods are being employed by zealots of several faiths to traumatise children into masking their autistic traits.

“Spiritual and ritual abuse is basically the modern day version of witch trials in the UK and the US,” says Shaun.

“And it is the one of the fastest growing forms of child abuse in the UK. It’s increased 43% in the last six years.

The Met Police define abuse linked to faith or belief as being “where concerns for a child’s welfare have been identified, and could be caused by, a belief in witchcraft, spirit or demonic possession, ritual or satanic abuse features”.

This can including physical, emotional and sexual abuse.

And according to The National Working Group on Child Abuse Linked to Faith or Belief, it is seen in extreme communities across multiple faiths in the UK, including traditional Christianity, Islam and Hinduism, as well as in some migrant African communities, and is not confined to one religion.

“What really got my interest was the impact it’s having on autistic people,” explains Shaun.

“What you find is that people who are quite extreme in their faith – all faiths, there’s not one that can be singled out – believe that the diagnosis of autism or ADHD isn’t real, because it doesn’t exist within their holy text.”

Coupled with Shaun’s view that common autistic traits have been – and are still – mistaken as signs of witchcraft in these communities, and there’s real cause for concern.

“You have young autistic people being physically beaten and assaulted by family members or religious leaders.” Shaun says.

“[In some places] they’re going through the equivalent of banned gay ‘conversion therapy’.

“And it’s often quoted in these kind of police reports that it’s evil spirits, or witchcraft, or it’s the devil who is possessing your autistic child.”

Shaun also highlights that in southern Africa, “very real witch trials are still happening“.

“In more rural areas, we are seeing people suffer from dementia – the confusion, the going walkabout, the mumbling – and having it equated to witchcraft.”

Online ‘vitriol’ won’t stop Shaun – but it stings

Closer to home, Shaun has been on the receiving end of “increasing vitriol” online (including threats and slurs) as a direct result of being openly autistic.

He’s also been harassed in workplaces for his “monotone” voice and “expressionless” face, both of which are traits of his autism.

He puts some of this down to kickback and “sensationalism” over increasing rates of autism diagnosis in society.

“There is often a lot of shame around being openly autistic,” he says candidly. “To talk about my experiences as an autistic adult invites ridicule. And a fair amount people preaching ‘get over it’.”

“It does sting. But I would still say to anyone who thinks they may have ADHD or autism, go and get checked out.

“For me, diagnosis was so important. That bit of paper allows me to exist in the world and access the help I need.”

Conversation