“Rolling up our trousers is about the strangest thing we do,” says Brother Peter Taylor.

“No, we’re not on a mission to take over the world. And no, we’re not the Illuminati.”

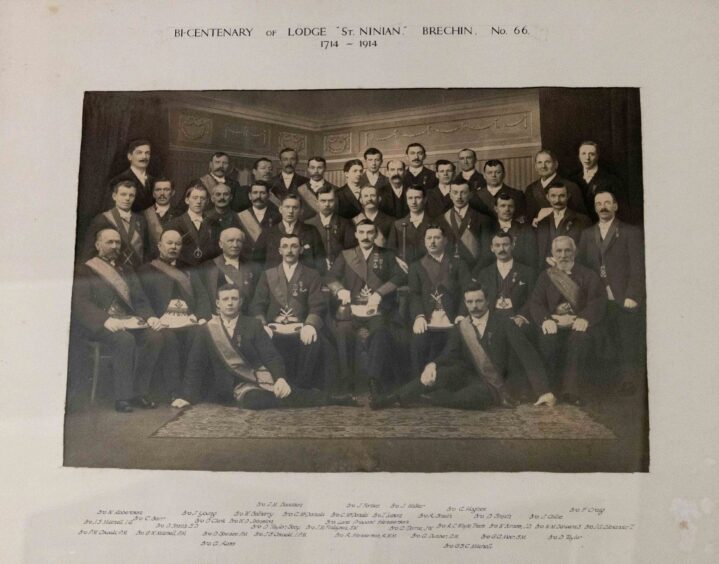

I’ve been invited into one of the oldest Masonic Lodges in Scotland – Lodge St Ninian’s 66 in Brechin.

As a woman, it’s both an intriguing and ever-so-slightly intimidating experience.

Here, among six, formally-attired men, I’m overwhelmed by the seeming pomp and ceremony of it all.

All are dressed in Masonic ‘regalia’. They wear smart black suits, ties, white gloves, and ‘aprons’ fashioned with intricate embroidery.

Dazzling gold pendants with arcane symbols hang round their necks.

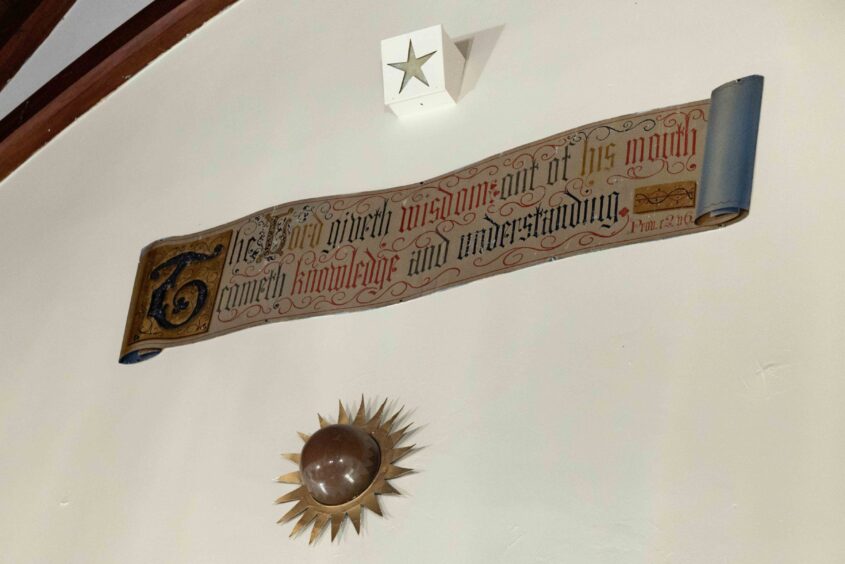

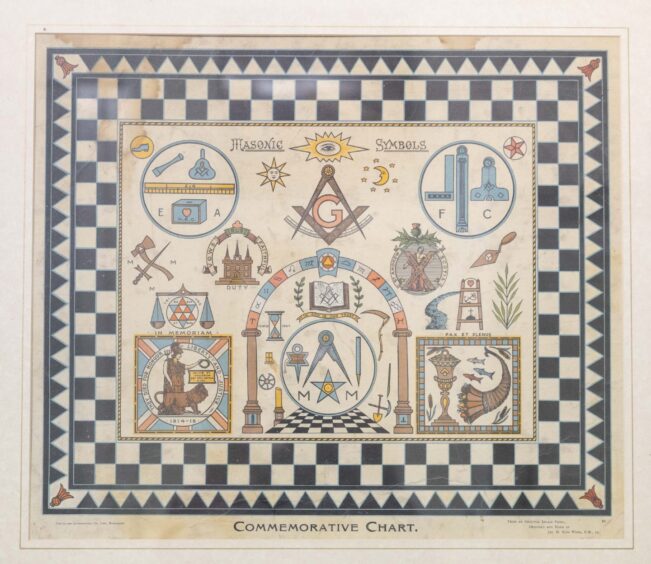

Freemasonry is steeped in symbols

Gazing around the lodge, which was founded around 1714, is a feast for the eyes.

There’s the ornately designed altar, with a big letter G (for God, or geometry) above it.

There are two majestic columns – symbolic of strength and stability – and the checkered floor, or ‘mosaic’ pavement’.

Candles, banners, photographs of past masters, and even a chunk of 12th Century stone bearing a mason’s mark, also catch the eye.

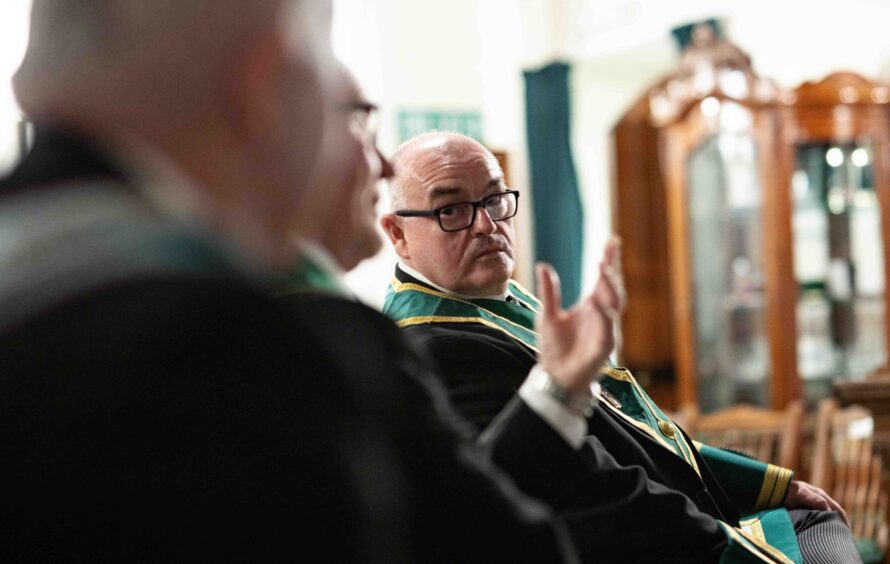

As someone with little clue about Freemasonry, I’m all ears when Peter, the Provincial Grand Master of Forfarshire, attempts to bust some myths about the so-called ‘secret society’.

“Freemasonry is most definitely not a religion, nor is it a secret society,” he tells me.

“It’s a system of morality veiled in allegory and represented by symbols.

“There’s a lot of archaic language used, and rituals going back 400 years.”

Masons must believe in a supreme being

When a ‘candidate’ joins the Freemasons, enquiries are made as to whether he’s of good character.

“The first question we ask is: ‘Do you believe in a supreme being?'” says Peter.

“We don’t ask him what that is. It doesn’t have to be a Christian God. It could be Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Taoist – anything. But not an atheist.”

The widely accepted view is that Freemasonry originates from medieval stonemasons who built many of our castles and cathedrals.

What of the Masonic symbols? Some are to do with the tools of stonemasonry, whether a hammer, square and compass, plumb rule, or trowel.

Then, of course, there’s the blazing star and the all-seeing eye – both symbols of God’s omnipresence.

“Imagine going back to the 1500s when masonry was based around stonemasons’ lodges,” says Peter, a retired quality manager at Michelin Tyres and grandfather-of-seven.

“Young apprentices were told all the tricks of the trade and sworn to secrecy. That’s where the so-called secrecy comes from.

“They were given morals and virtuous lessons, based on King Solomon’s Temple – the first stone building ever to be built.”

What about Masonic rituals?

I can’t resist bringing up the rituals – I’m fascinated by the idea of secret handshakes and bizarre initiation ceremonies.

There’s a lot of theatre and drama, but it doesn’t seem to me there’s anything sinister going on.

“When a person joins, he becomes the central character in a play,” explains Peter.

“We take him through a ceremony where he’s taught certain lessons about morality, charity and virtue. That’s part of the first ‘degree’.

“Some lodges dress up the new boy to look a bit silly. We don’t.

“But you’ll have heard about rolling trouser legs up. That’s probably the strangest thing we do.”

So how does that work – and what is the point?

“He would kneel down, barefoot and bare-kneed, at the altar, and take an oath on a very old bible,” explains Peter. “It’s about being closer to consecrated ground.”

The display of a bare leg is also meant to demonstrate that candidates are free men: they’re not wearing shackles.

A bit like ‘frat houses’

John Hayes, 55, the Provincial Grand Secretary of Forfarshire – and a senior lecturer in history and political studies at Dundee and Angus College – elaborates further.

“It’s part of an initiation in Freemasonry, similar to what you might get in frat houses in American universities and the public school system here,” he explains.

“The new boy will always be made to look different.”

It’s a nod to the rituals of the 1600s, explains Peter, adding that there are sections of ancient text which refer to candidates being “affrighted” during initiation ceremonies.

“They might get pushed around a bit; people will make fun of them,” he smiles.

Peter refers to other “wee quips”. I wonder if he means newbies having knives pointed at their bare chests, and being blindfolded with ropes round their necks?

Such things happen, apparently, but when pressed, Peter says he promised not to divulge details.

“Exposing them would probably spoil the experience for someone joining,” he adds.

He admits there are “other, seemingly to the outside world, strange goings on in terms of the preparation of the initiate”, adding that while they may seem “bizarre” that there are “basic reasons” for it all.

‘It’s not a secret society’

While Freemasonry is not a secret society, it is a society of secrets, with handshakes, signs and passwords, known only by members.

“All they are is modes of recognition,” Peter clarifies. “For medieval Freemasons, they were the equivalent of a pin number restricting access only to qualified members.

“We take an obligation not to tell anyone what they are.”

However, if you’re desperate to find out, you can track down a copy of what Peter refers to as “Duncan’s exposé” – Duncan’s Masonic Ritual and Monitor, written in 1866.

Don’t mention Monty Python

The handshakes, explains Peter, are universal. Have I seen the Monty Python sketch which mercilessly mocks Masons? I have indeed.

“It’s nothing like that,” smiles Peter. “You take a brother’s hand a certain way, that’s all.

“There’s a sign which goes with that. You make a gesture with your arms or your hands.

“There are different grips, or handshakes, different signs, and different passwords used in the degrees.

“The password would be used, for example, if you wanted to gain entrance to a lodge in Malaysia, the States, England, or wherever.

“They might say, we’re going to be working a second degree, so give me the second degree handshake, sign, and password.”

Secrecy is for ‘ruling out imposters’

John adds: “You could buy the regalia we’re wearing off the internet. If you knew there was a lodge meeting you could just stroll in.

“So we need to test you – to make sure you’re not an imposter.”

So who does Freemasonry appeal to? And what benefits are there in joining?

With membership falling over the last 20 years, the ambition is to bring in fresh blood – and to get young men on what the Freemasons argue is a spiritual, meaningful path.

How relevant is Freemasonry in 2024?

“My belief is that young men are looking for some kind of spirituality and sense of belonging which they maybe don’t think they can get from the church or any other organisation,” reflects Peter.

“This organisation gives them tools to make their own path. Our job is to make good men better.”

Becoming a Mason is also a great way to combat loneliness.

“When you join the lodge you get instant friends,” says John. “Some of our members worked in the oil industry abroad.

“A hotel can be a lonely place in Azerbaijan but you can get out to a lodge meeting with your regalia and meet folk.”

For young men – they can join at 18 – it can be a great confidence booster, teaching them skills like public speaking.

Fun and friendship among men

“The initiations give men from all walks of life the chance to stand up in front of an audience, and face their fears,” says John.

“People don’t always associate fun and enjoyment with Freemasonry but it really is about camaraderie and making lasting friendships.”

Freemasonry also acts as a support network for men who’ve lost their wives or partners, or simply lost their way in life, he adds.

“We get a lot of men coming out of the forces,” says John. “They don’t know how to adapt to family life and a nine to five job. Freemasonry helps them on that road.”

The vast majority of Masonic lodges are for men only – but some do admit women.

I ask Peter why focus mainly on men? It is, after all, 2024 when even long-standing male-only hold outs – such as Edinburgh’s Muirfield Golf Club or London’s Garrick Club – have changed their policies within the last decade.

“It’s a tradition – it’s been men-only for hundreds of years,” says Peter. “It’s not a sexist thing.

“I don’t care if you’re a Martian. But I also believe my organisation is designed to improve men.”

Freemasonry: a conspiracy theorist’s dream

It’s no surprise that conspiracy theorists dream up wild ideas about Freemasonry – but this doesn’t faze them.

“There’s a lot of speculation,” says Peter. “We’re obviously not a secret society because you’re sitting here talking to us.”

John admits it was the mystery, intrigue and “subterfuge” surrounding Freemasonry that drew him to it.

“People ask: ‘Are you the Illuminati? Are you the New World Order?’ I love all that curiosity,” he beams.

What about those who accuse Freemasons of being corrupt?

There’s a strict disciplinary code, and anyone found to have broken rules, and engaged in ‘un-Masonic’ conduct – perhaps seeking to use their position to gain pecuniary or business advantage – could be suspended or expelled.

“It’s a complete myth that you join the lodge to get a lift up the ladder,” scowls Peter.

Freemasons are well known for doing good in communities and supporting charities.

“There are raffles, formal dinners, collections and sponsored walks, bike rides and swimming challenges to raise money for charity,” says John.

And there’s a strong social aspect – Freemasonry is very family-oriented, with suppers, dances and special events laid on.

Meanwhile, the Masonic almoner is a key figure, providing support to members, visiting the sick, aged and infirm.

After almost three hours in the lodge, we finish with tea, biscuits and laughter.

Based on my visit, I can see Freemasonry’s appeal as a life-enhancing organisation for many, and the fact it retains such an air of mystery – in my opinion – is pretty cool in this day and age.

Conversation