When Dundee writer Sophie Gackowski died in 2018, she left a lot of life – and a stack of paper diaries – behind.

In her Broughty Ferry bedroom, time stands still: her vibrant artwork adorns the walls; her pillow and her knick knacks sit poised for use, as if she’s only just popped out.

But her parents Peter and Petula have felt each and every moment of the six years since their precious Sophie’s life was cut short by a rare and aggressive cancer.

“Sophie was an amazingly clever young lady,” says dad Peter.

“She had a lot of potential, and unfortunately it wasn’t fulfilled.”

Sophie’s illness started with pain in hand

Sophie was just 18 when she started experiencing pain in the palm of her hand, which was initially attributed to carpal tunnel syndrome.

But this was later found to be caused by Epithelioid Sarcoma (ES), a form of cancer that attacks the soft tissue.

To give her a chance at survival, Sophie had her right hand and part of her arm amputated in 2014. Her body and life were altered, but for a time, she was cancer-free.

Undeterred by the loss of her dominant arm, she learned to make clay miniatures with her left hand, and threw herself into writing stories.

Then in 2015, a CT scan showed the cancer had reappeared in Sophie’s lungs. She was told the next year that it was terminal.

After two more years of exploring alternative therapies to prolong her life as much as possible, “free spirit” Sophie passed away at Roxburghe House, using her last words to tell her family: “I love you.”

Dundee writer’s voice lives on in new book

When she died, Sophie was just a few months shy of her 30th birthday – the same age I am as I sit down at her parents’ dining table.

The parallel hangs heavy in the centre of the room: I am here. Sophie is not.

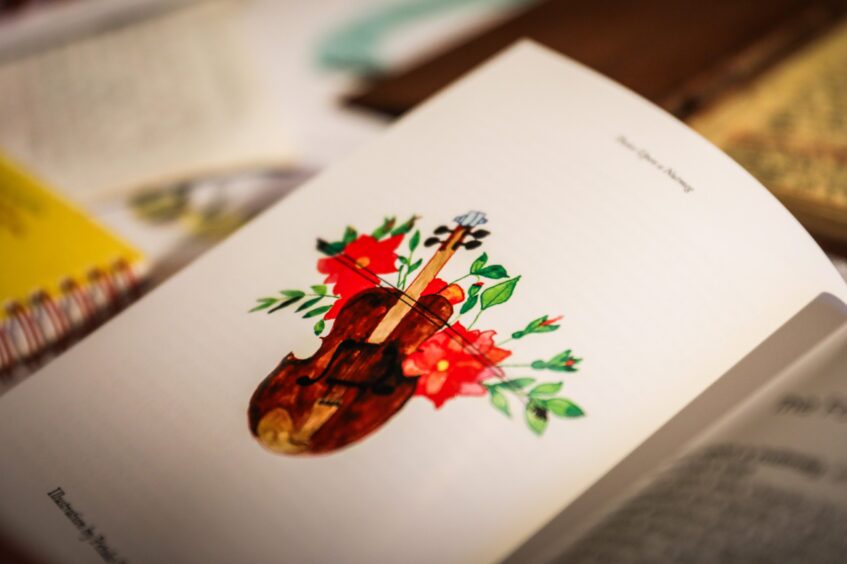

But her voice sits on the table in front of me: a slim, beautifully-bound hardback volume of stories and diary entries, painstakingly transcribed after Sophie’s death by her dad Peter, and illustrated by mum Petula.

This book, Peter explains, will be Sophie’s legacy.

Stories gave parents comfort in grief

The idea to create the book came to Peter and Petula in the months following Sophie’s death.

“Obviously after she died, you go through that period of not wanting to throw anything away,” Peter recalls.

“When we eventually went through all her stuff, we found all these stories on her laptop. We knew she wrote stories – she would get Petula to read them sometimes.

“But we didn’t know she’d been writing quite so much.”

Sophie’s parents were heartened when they read their daughter’s whimsical, escapist short stories featuring grumpy mirrors and unloved bird baths.

Her opening line for each tale – “twice upon a nutmeg” – echoes a phrase that Sophie’s grandfather would use when he told her stories as a child.

“They were a bit like Alice In Wonderland,” Peter smiles. “She wrote them, I think, just to keep herself engaged with hope.

“She knew she was facing into death. Still, she was amazingly pragmatic about it.”

Sophie Gackowski’s diaries contained her hidden fears

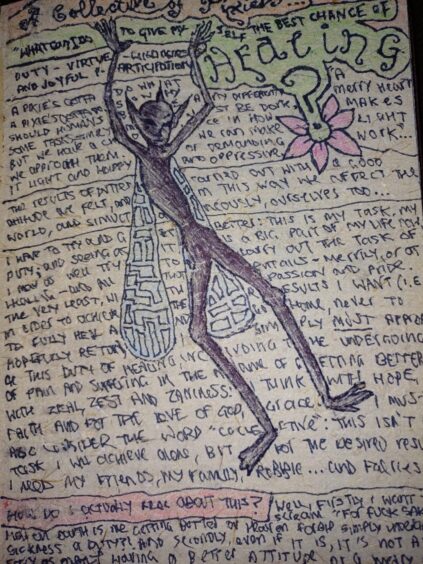

But it was when they came across a box of Sophie’s old diaries that they were struck by the pure emotion of their daughter’s writing as she wrestled with her diagnosis.

“When we went through her diaries, a lot of it was writing we hadn’t seen [when she was alive] because they were private,” explains Peter.

“They were really well-written, so full of emotion. It was surprising, because it was so personal.”

Many of us might balk at the idea of our loved ones reading our journals, but Sophie’s mum Petula says it was clear from the writing that “she wanted us to see them at some point”.

And reading Sophie’s diaries provided her parents an even deeper insight into a daughter who had always been, as far as they were concerned, an open book.

“She was pretty open,” Petula says. “But even so, when you read her thoughts as they’re going on to paper in her diary, you can tell she was frightened.”

One aspect of the book which particularly struck Sophie’s parents was her letters to herself.

In them, she wrestles with feelings of regret about the ways she may have damaged her body before her cancer diagnosis.

“When Sophie was a teenager, she did what all teenagers do – things she shouldn’t,” continues Petula with a chuckle.

“Getting tattoos too early, and piercings; kissing boys too early. Smoking, alcohol.

“You can see she regrets all that, what it did to her body. But by the end of the book, she’s come to terms with it all.”

Dad Peter transcribed daughter’s diaries

For Peter, transcribing Sophie’s hand-written diary entries was a “difficult” labour of love.

“She had several notebooks, and lots and lots of paper,” he smiles. “I went through it all systematically, then transcribed everything she’d written on to a Word document – the letters, diary entries, everything.”

After compiling all of her works, Peter sent them to family friend and Sophie’s former classmate, Dr James Morris.

Dr Morris helped Peter to select which stories and entries would work well together in a finished book, while keen painter Petula set about creating colourful illustrations to accompany her daughter’s writing.

The book was then typeset and designed by another close family friend, graphic designer Roland Proctor.

Peter and Petula are “elated” to finally be able to hold copies of the book that Sophie “would have wanted” in their hands, six years on from her death.

‘How do you reconcile losing a daughter at 29?’

Of course, the moment was bittersweet for those who loved her.

“Was it easy to do? No, of course it wasn’t,” Peter concedes. “It was emotional. Whenever I revisit her work, I find it upsetting.

“But from a distance, I really do find it inspirational and uplifting. I think anyone going through cancer or facing death would get something out of it.

“People will ask, how do you reconcile losing a daughter at 29? And you do it by looking forward.”

Now, 200 copies of the book have been published. And Peter and Petula are selling them off with the hopes of raising at least £1,000 for cancer support charity Maggie’s.

At the time of writing, £906 had already been raised through book sales.

“Sophie went on a weekly basis to Maggie’s, talking to her counsellor Charlotte about all her hopes and fears while going through cancer,” Peter explains.

“I was staggered at how much it costs to keep it open – £700,000 a year. It helps an awful lot of people.

“And Sophie made an impact on people, so that’s also why doing this has been so important. We want to keep her memory alive and have a legacy for her.

“She didn’t die in vain. Her work lives on for other people.”

You can buy Twice Upon a Nutmeg by Sophie Gackowski for a £10 donation plus postage with all proceeds going to Maggie’s. Email: pgack@hotmail.com

Conversation