Right at this moment, the Stone of Destiny is safe in its glass case in Perth Museum.

But it’s also in Queensland Museum, Australia.

And it’s also in Canada, as well as in various locations across Scotland, and beyond.

The block of Perthshire sandstone sat on by kings during their inaugurations since at least the mid-13th century has acquired a mythical legacy over its long lifetime.

Nonetheless, it hasn’t got magical powers. It can’t teleport, nor be in several places at once. The truth is simpler but no less fascinating.

Scottish stonemason and politician Robert ‘Bertie’ Gray died 50 years ago this April, but he’s been on the mind of the University of Stirling’s Professor Sally Foster a lot lately.

Bertie Gray took on the job of mending the Stone of Destiny (also known as the Stone of Scone) in 1951, after it broke in two following its rebellious removal from Westminster Abbey by a group of Scottish students.

In reality, his colleague Edward Manley did most of the hard work. But, as Professor Foster discovered last year, Gray was busy while the repair took place.

“When I began my research, nobody knew, myself included, that there were lots of fragments of the Stone out there,” the heritage professor explains.

But many hours of investigation have revealed that Bertie Gray collected and carefully curated tiny pieces of the Stone of Destiny which chipped off the weathered sandstone block during the course of it being joined back together.

34 numbered ‘relics’

Professor Foster now believes Gray gathered 34 fragments, treating each one as a numbered relic, as well as other small chips and grains of the Stone.

“From 1951 until 1974, for sure, he gives these to people,” she says.

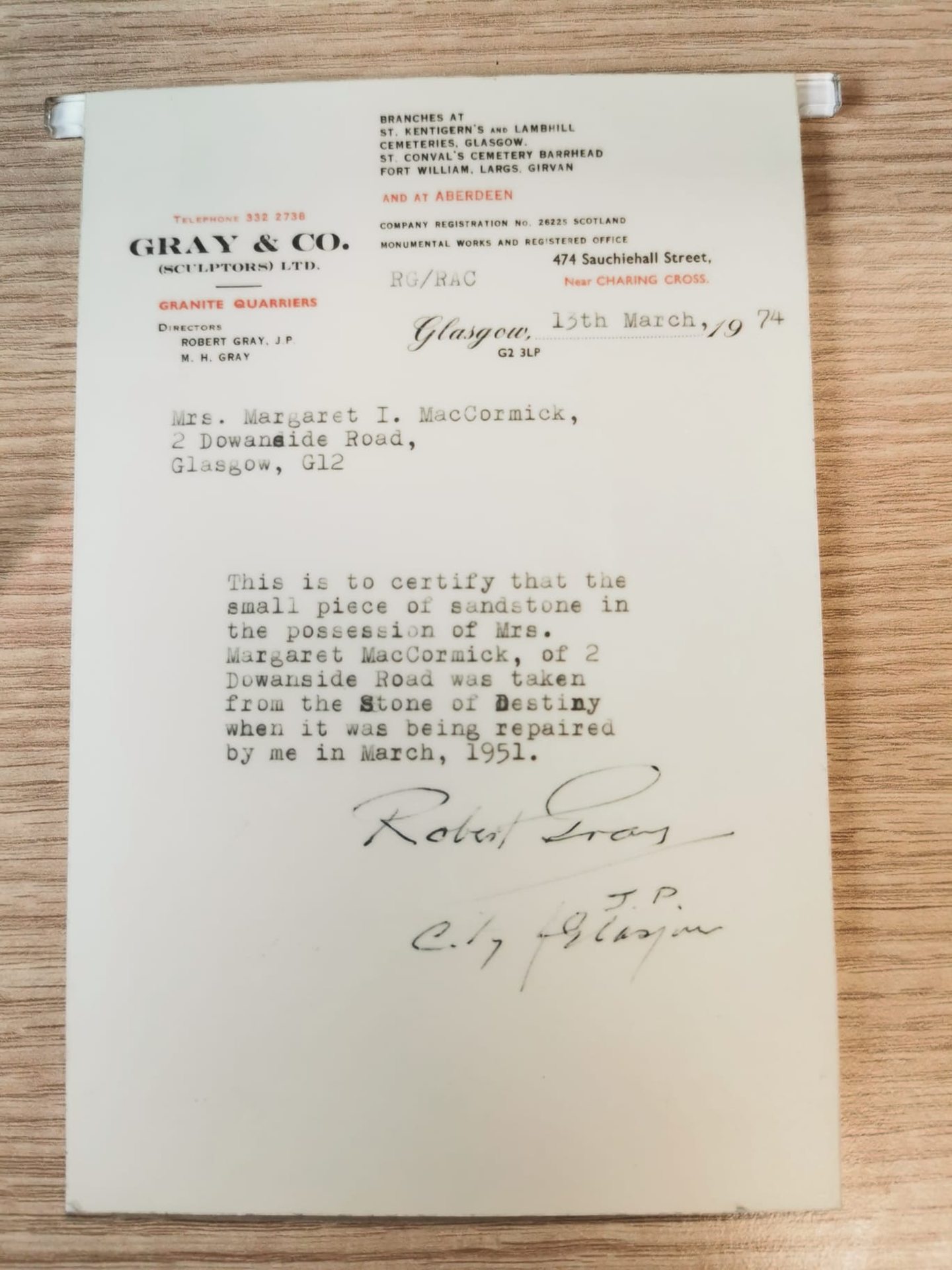

“In quite a lot of instances, he’s giving them to people with a letter of certification.”

She adds: “He’s quite tactical, really, in who he’s giving them to.”

Gray handed over fragments of the Stone to three (if not all four) of the students involved in its removal from England, to people involved behind the scenes of hiding it in Scotland, to Scottish politicians, to a Canadian journalist, and to at least one Australian tourist, who took it home.

He also gave one to his daughter, with a letter of authenticity dated December 4, 1974, which she put up for sale in 2018, and is now in the care of Historic Environment Scotland.

This development didn’t go unnoticed by Professor Foster, who worked for Historic Scotland in 1996 when the Stone of Destiny was officially returned to Scotland, before moving into academia in 2010.

And, over time, her research around the Stone kept leading her to clues hinting at the existence of further fragments.

She found intriguing and amusing crumbs of evidence at Gairloch Museum, in the University of Stirling’s Scottish Political Archive, and in newspaper clippings from decades gone by.

But the fragment that broke the camel’s back, if you will, was given by Bertie Gray to Margaret MacCormick, wife of Scottish politician John MacCormick, in 1974.

The penny dropped for Professor Foster when that particular wee chunk of Perthshire sandstone hit the headlines and caused “uproar” in January 2024, after Scottish Cabinet papers revealed its whereabouts.

In 2008, it was gifted, by the MacCormicks’ son Neil, to then First Minister Alex Salmond, and stored at SNP headquarters.

“I had already tracked it down, but the media coverage made me start to think: ‘Wait a minute, these fragments are really quite powerful in terms of the stories that they have’,” says Professor Foster.

Stone’s meaning has evolved over time

The “long lives of objects” dating back to the first millennium AD have always fascinated the academic, who began her working life as an archaeologist.

She is particularly interested in the social value we humans give to carved stones, and how their perceived meanings and importance fluctuate over time.

The Stone of Destiny (which myths suggest could have origins in that early-medieval period) is a shining example of this.

“It’s a very simple thing. It’s a very unprepossessing thing. But it’s clearly had a life,” says Professor Foster.

Wrapped in layers of fact, fiction and legend, the Stone has always had a ceremonial purpose.

But, since its symbolic removal from Scotland by King Edward I in 1296 and consequent defiant return more than 600 years later, it has come to mean a great deal more to many Scots.

Some see it as a hopeful emblem of Scottish independence, while others cherish its historic significance and role in the coronation of multiple monarchs, right up to King Charles III in 2023.

So, perhaps it’s no surprise that anyone who came to own a small sliver of such a meaningful item would treat it with care, passing it down to family members through the generations.

‘Fragments are out there and being cared for’

Though officially still unaccounted for, Professor Foster believes a lot of Bertie Gray’s fragments are being “cared for”, or “stewarded”, by families across Scotland and further afield.

Helped by member of the public and “rigorous researcher” Richard Keltie, she has begun the process of tracking them down.

“There are references emerging where people had them put in keyrings, maybe set in watches, or in a kilt pin,” she says.

“Sometimes they are just fragments, still, with a letter.

“They’re out there. They’re being cared for in private hands.”

Since news of her search for the fragments caught the nation’s attention, the professor has been inundated with emails.

She has seen photographs of phials of dust, said to be collected during the Stone of Destiny’s repair, and of several more of Gray’s fragments which prove that he did directly number some of them.

She has learned new stories – about the people who received the fragments, how they were cared for, how they were shown to others, and how they were valued by each household.

And, she says, it is emerging that there are more than just Bertie Gray’s fragments in existence.

The search continues

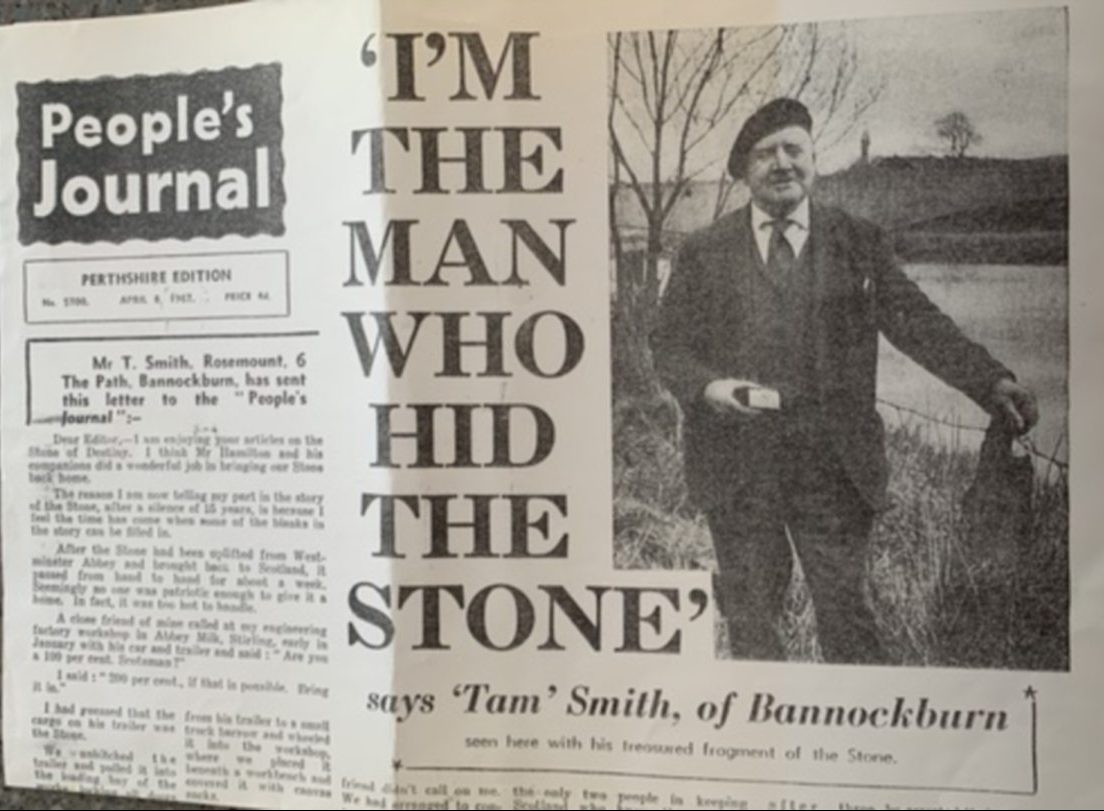

For a brief time, half of the Stone of Destiny lay hidden in a Stirling engineering works, watched over by a local man called Tam Smith.

In the late-1960s, Mr Smith admitted to taking his own fragment as a precious souvenir, keeping it in a matchbox. His grandson believes he was buried with it.

Though time and funding is required for the next phase of research, the Stirling academic hopes to see more fragments for herself and meet the people who are caring for them, all the while collecting stories that come back to the Stone.

And, of course, new clues “hidden in plain sight” are popping up all the time.

Professor Foster says she recently came across an archive newspaper article that referred to a 1955 Scottish Covenant Association raffle.

The second prize was a brooch made using a piece of the Stone of Destiny.

She jokes: “You just think: what was the first prize?”

For more Stirling news and features visit our page or join us on Facebook

Conversation