With Halloween almost upon us, Michael Alexander explores some of the haunting tales associated with notorious burial sites in Tayside and Fife.

The higglety-pigglety jumble of gravestones sit at jaunty angles to one another as autumn leaves rustle in the wind and long shadows point towards the shorter days ahead.

Here in the Howff cemetery in the centre of Dundee, faded, crumbling, forgotten stones dating back centuries hint at the city’s social – often tragic – history where thousands of children died young and where disease showed no respecter to social status.

Yet for the majority of people buried over the centuries in the Howff – which is renowned for its high number of Roman-style coffer tombs – there is no gravestone marker at all.

“The conservative estimate of how many bodies are in here is between 80,000 and 100,000 in comparison to the 1200 gravestones that are here,” explains Stewart Heaton, 37, who owns and runs Dark Dundee walking tours with his business partner Louise Murphy, 36.

“But if you think about things like the infant mortality rate and the fact there are a lot of people buried in here we don’t know about it could go anywhere up to 120,000 or 150,000 dead bodies.”

The history of the Howff dates back to 1260 when a monastery was built there. But it wasn’t until the mid-1500s that the grounds of the by then post-Reformation ruins were turned into a graveyard after the land was donated by Mary Queen of Scots.

Very quickly, however, and with disease and poverty rife, it became overcrowded.

Stewart adds: “In the early 1800s there was about nine feet of earth put back in here because there were so many bodies in the ground.

“Gravediggers just couldn’t get a spade in without what they quoted as ‘white foam’ coming back out on their spade, so the council of the time decided they’d put extra earth in here, and that allowed the burial of even more bodies.”

One of the loneliest gravestones can be found at the rear of the cemetery. It belongs to Lt Col William Forrest who died of cholera on his way up to Dundee from London in 1832.

However, he is just one of 512 Dundonians who died from a cholera outbreak in the city – likely caused by polluted water supplies – and he sits above an unmarked cholera pit which lies beneath today’s cobbled path.

“In 1832 over 30 weeks, 800 people got infected in Dundee and 512 died just of cholera,” explains Louise.

“They decided they needed to build a cholera pit to put all these bodies in them. They didn’t just turf the bodies in. They made make shift pine coffins but they did need to bury them deeper than they normally would and they would just pile the coffins on top of each other five or six deep, fill it with lime and a bit of earth.”

The ‘new’ Howff – was built north of the ‘old’ Howff in the 1860s. That site was redeveloped in the second half of the 20th century to make way for what is now the city’s Bell Street car park and Abertay University with most of the bodies exhumed and relocated to the city’s Eastern Cemetery.

But elsewhere, some remains are thought to remain in situ.

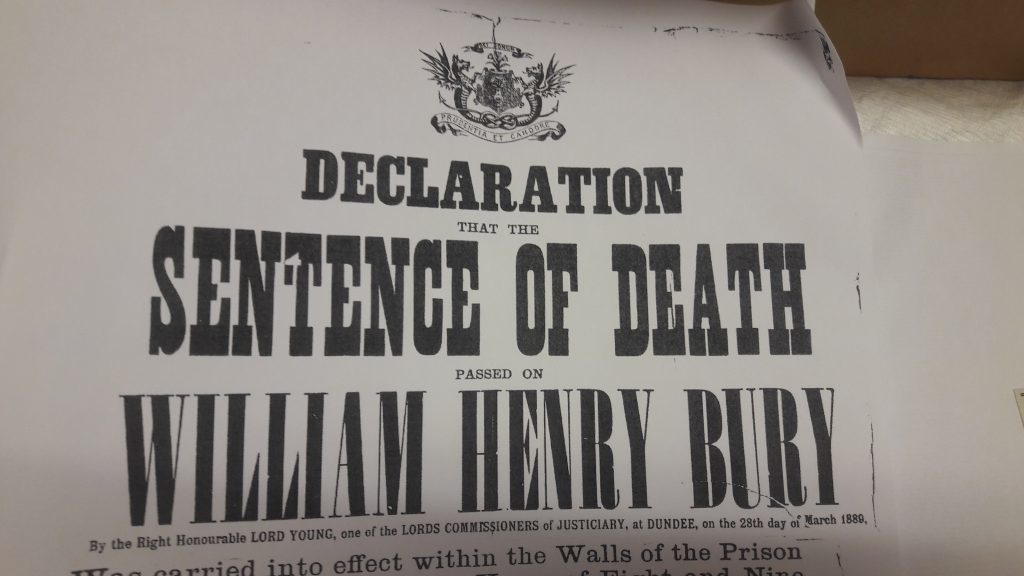

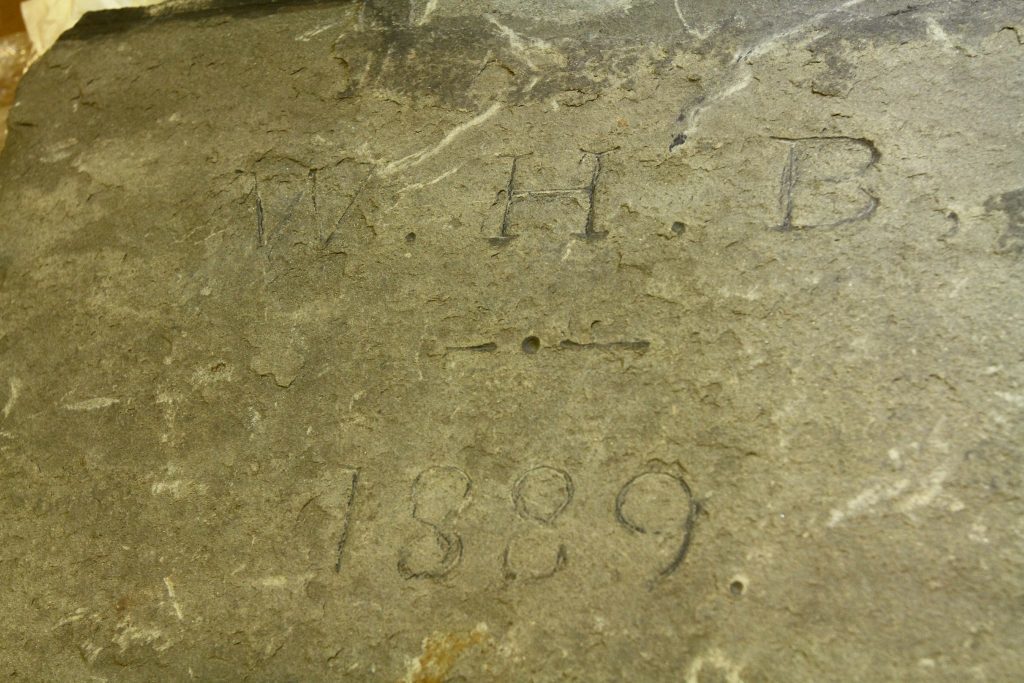

One such resting place is that of William Bury who was suspected of being the notorious serial killer Jack the Ripper. He was hanged in private for the murder of his wife Ellen in 1889 and was the last person executed in Dundee.

According to Boston-raised Christina Donald, curator (early history) at The McManus Collections Unit in Barrack Street, Dundee, his remains are likely still under today’s Police Scotland HQ car park at Bell Street which used to be the site of the old Dundee Prison burial yard behind today’s court house.

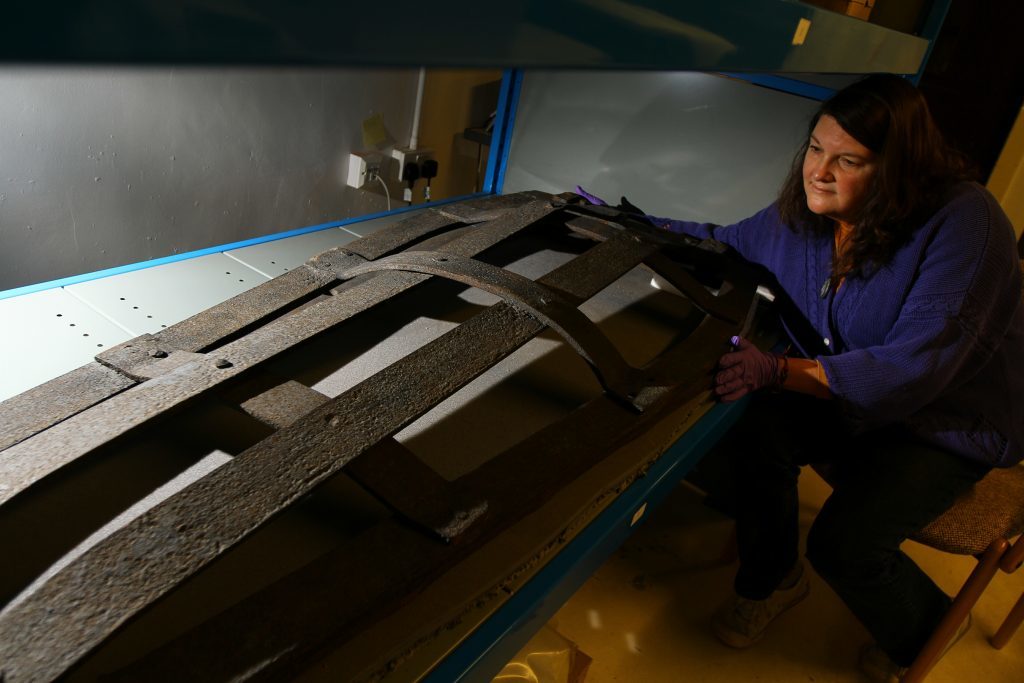

His burial stone was taken out of the wall of the old prison yard in the 1970s and has been with the museum ever since.

“The evidence as to whether he might have been Jack the Ripper seems to ebb and flow,” says Christina, “but he did live in Whitechapel, London, and the murders down there did stop when he moved to Dundee. They were only in Dundee very briefly but he did kill his wife and dismember her in the city and is said to have confessed to the hangman that he was Jack.”

Other gory artefacts stored in the Collections Unit – each with their own fascinating tales – include the plaster cast phrenology head of Dundee sailor David Balfour who murdered his wife in 1825 after returning home to find her living with another man.

After being publicly hanged in front of an 18,000 crowd, his body was sent off to Edinburgh for dissection and a death mask was made to help study whether head shape could pre-determine someone’s likelihood to commit murder!

The diverse collection in storage, which is sometimes displayed at McManus on rotation, also includes a wrought iron mort safe, which could be rented from the council to deter body snatchers in the 19th century.

Other artefacts include human remains from Pictish graves excavated at Lundin Links and a 4000-year-old Egyptian mummy Henty-Ka-s which was brought to Dundee by philanthropist Sir James Caird in 1892.

“Not too much is known about Henty-Ka-s’ life,” adds Christina.

“We think she was elderly. She had four teeth and signs of arthritis. On her coffin she’s a young lady in a see through dress which is how she wanted to be seen in the afterlife! And why not!”

Elsewhere in Courier Country there is no shortage of haunting burial sites. From the hanging tree and beheading pit at Finlarig Castle, Killin, to the monument and Covenanters graves marking the murder site of Archibishop James Sharp in 1679 at Magus Muir, near St Andrews.

From the Balfour Stone in the Pass of Killiecrankie marking the grave of Brigadier Barthold Balfour who commanded part of the Red Coat army at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689, to the 18th century communal grave at ‘Witches Corner’ in Pittenweem, there are no shortage of gruesome tales to be unearthed.

Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs is an expert on 6000 years of burials in Fife.

These range from the Neolithic/Bronze Age excarantion platform at Balbirnie (Glenrothes) where, 4000 years ago, bodies were left on a platform to rot to skeletons before being buried; through to Pictish kingly cairns on hill-tops and extensive pre-Christian Pictish barrow cemeteries.

He is fascinated by the mass grave pits created after the Battle of Pitreavie, fought between Cromwell’s English Parliamentarian New Model Army and the Scots Royalists near Dunfermline in 1651.

Two mass graves of 50 or so people each were found in the 1850s at Pitreavie but the missing c.1400 dead Scotsmen from the battle have not yet been found even though it’s known where the battle was fought and where they died.

“It’s possible that many of them were removed without notice during the building of the M90 Pitreavie spur road in 1968,” adds Mr Speirs. “I think it possible that many burials were scooped up by earth-moving machinery.”

Another of his favourite tales, however, relates to the Torryburn revenant witch burial.

Back in 1704, Torryburn on the south west Fife coast, had what was regarded as a toxic witch problem.

Lilias Adie, a poor woman who confessed to being a witch and having sex with the devil, died in prison before she could be tried, sentenced and burned.

So they buried her deep in the sticky, sopping wet mud of the foreshore – between the high tide and low tide mark – and they put a heavy flat stone over her.

“The unusual and costly burial and what it tells us about the degree of superstition believed, even by the authorities at this time,” says Mr Speirs.

“A significant amount of thought, time and money was expended by Culross Town Council on disposing of the body of the deceased accused witch.

“Rather than just bury her on waste ground as was common, they were so scared of this wronged witch coming back to life after death to seek her revenge that they arranged for her to be buried at sufficient distance from Culross, beyond a stream witches can’t follow; buried in unconsecrated ground in a liminal place between land and sea – a place traditionally reserved for the disposal of the damned eg suicides, the unchristened and those who could not enter heaven; and they paid for a large slab of sandstone to seal the grave to prevent her rising from the dead.

“For the municipal authorities to have spent so much of their limited budget on disposing of a witch when they had many more important things to spend their money on, like alleviating poverty and staving off the starvation of the poor shows that the authorities were genuinely concerned that this witch rising from the grave was a very real possibility and a very real public safety issue!”