How did visitors to Stirling spend their holidays more than a century ago?

Thanks to the University of Stirling’s impressive archives, we can tell you.

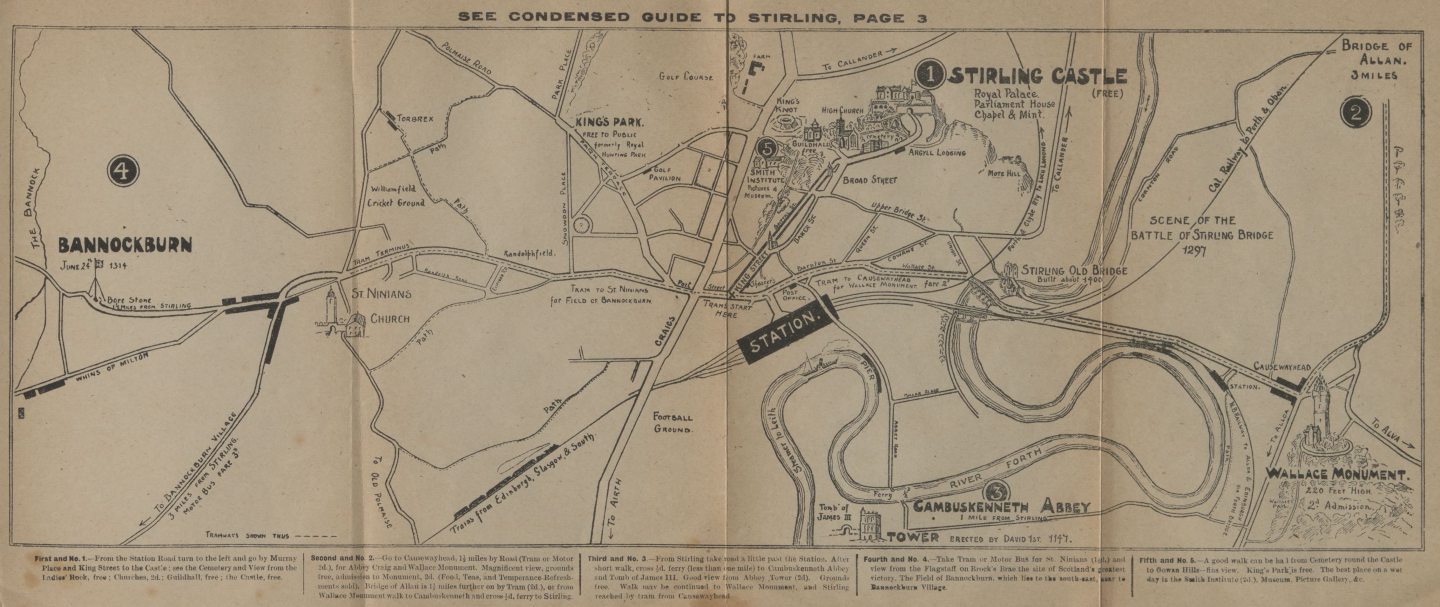

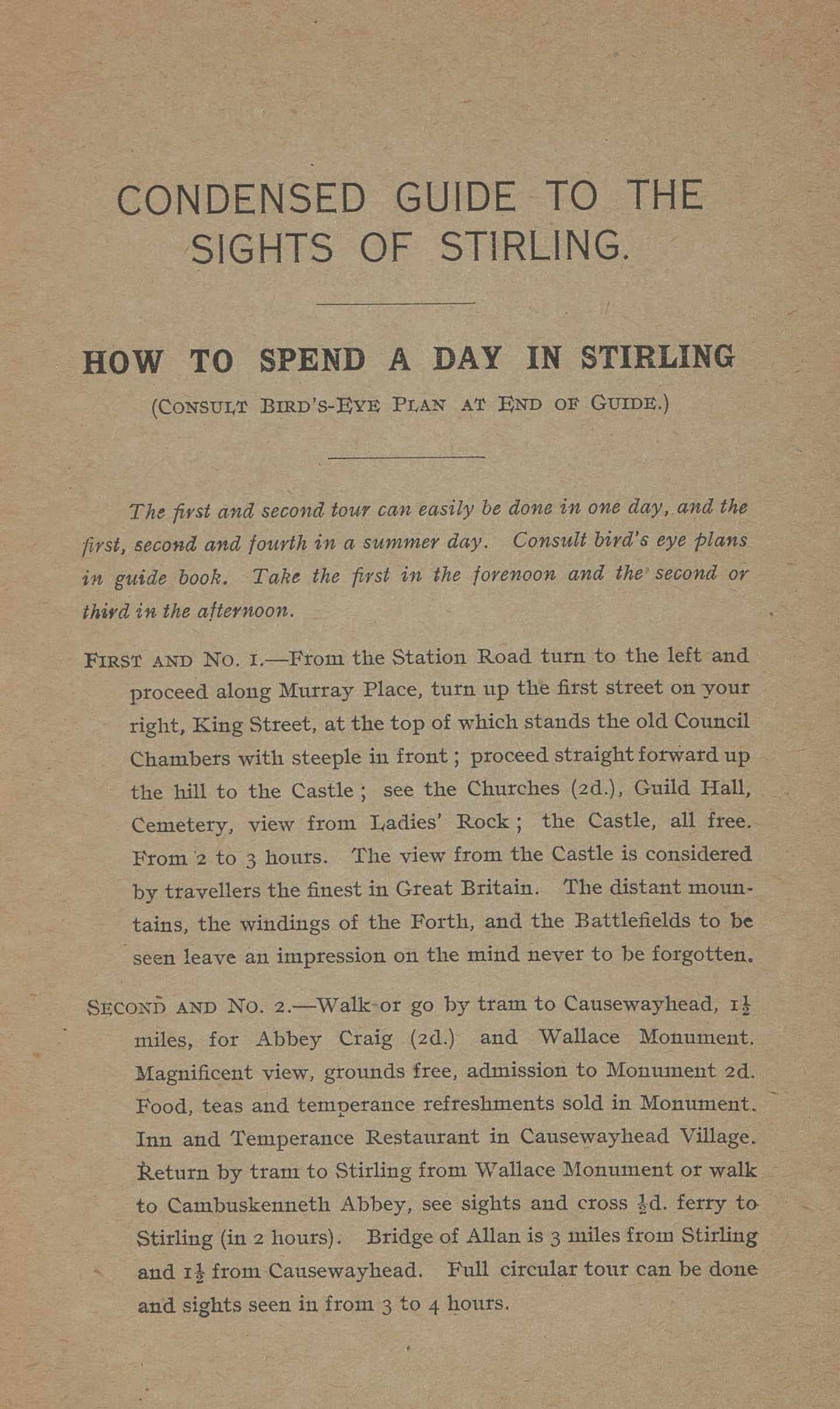

Shearer’s Visitor’s Companion and Pictorial Guide to the sights of Stirling was published in 1919, and features detailed tours and maps of the city as it was then.

The guide is included in the university’s free special Stirling 900 exhibition (on at the Macrobert Arts Centre until May) so anyone can pop by to have a look.

As soon as The Courier’s Stirling reporter Isla Glen and I set our eyes on it, we knew we’d be taking a trip back in time – no time machine required.

(Which is lucky, because I’m not sure our budget would have stretched to that.)

Read on to find out how we got on exploring Stirling through the eyes of a tourist 106 years ago.

It’s 1919. War is over, the Roaring Twenties are on the horizon, and it’s time for a holiday – or, at the very least, a grand day out.

And where better to spend a spring day than Stirling?

After all, according to Shearer’s guide, “the view from the Castle is considered by travellers the finest in Great Britain.”

It goes on: “The distant mountains, the windings of the Forth, and the Battlefields to be seen leave an impression on the mind never to be forgotten.”

More than a century later, is that still the case?

Before we can find out, Isla and I have got a hill or two to climb. That certainly hasn’t changed in the last 106 years.

Murray Place and King Street

Combining elements of several suggested walks around Stirling from Shearer’s guide, we start our adventure at the railway station.

Regrettably, tourists can no longer arrive in the city via a steamboat from Leith like they could in 1919, as highlighted on one of the guide’s detailed maps.

But construction of Stirling’s current station finished in 1915, so (mod cons aside) the building probably doesn’t look that different to when tourists were arriving by train more than 100 years ago.

From Station Road, Isla and I turn left onto Murray Place.

The businesses there might be modern, but many of the buildings and the road paved with setts likely look very similar to how they would have in 1919.

Our first official stop, the striking Athenaeum at the top of King Street, certainly hasn’t changed, with its tall steeple, ornate carvings and statue of William Wallace.

Built in 1817, the structure was already more than a century old in 1919.

Shearer’s guide describes it as “the old Council Chambers”, but it was originally opened as a library.

Today, it lies empty and is perhaps in need of a little TLC, but is still a unique and beautiful landmark worth admiring.

Cemetery and Ladies’ Rock

We carry on uphill, along Spittal Street.

En route, we point out buildings that our 1919 counterparts would have seen on their own travels, like the former Stirling High School (now Stirling Highland Hotel), and others they sadly missed out on, like Wetherspoons.

Our next stop is the sprawling Old Town Cemetery.

It might sound strange now, but during the Victorian era, Stirling strived to make this a real tourist destination – it was designed to be a nice, welcoming place for a stroll, and there are plenty of interesting monuments to look at.

Some of these memorials and statues are obviously in need of maintenance, such as the eye-catching Martyrs’ Monument, and I hope they are taken care of for many future generations of visitors.

There’s no doubt the graveyard was still a lovely spot in 1919, just as it is today.

In fact, it’s one of Isla’s personal favourite “happy places” in the city, where she says she feels most at peace.

We survey it from the top of Ladies’ Rock, a crag and fantastic viewpoint within the cemetery, taking a moment to sit on the bench there.

Stirling Castle

Another hill, anyone?

We make the short yet steep trip from the cemetery to Stirling Castle.

Shearer’s guide tells us the iconic landmark is free to visit. Unfortunately, that’s no longer the case in 2025, unless you’re under the age of seven.

Today, adults are charged up to £20.50 for a ticket.

Since we’re tight for time, Isla and I instead choose to enjoy the aforementioned unforgettable view from the castle esplanade which, I’m pleased to report, still costs nothing.

There might be more housing estates and retail parks incorporated into the finest panorama in Great Britain these days, but the imposing backdrop of the Ochil Hills remains the same.

Even on a cloudy, somewhat moody day, the sight of Stirling’s special and stunning landscape makes a lasting impression.

Cambuskenneth Abbey via ferry

Our next stop is one of my favourite places in Stirling: Cambuskenneth Abbey.

Getting there from the castle involves a bit of a walk and, according to Shearer’s guide, a ferry. We’re very excited at the thought.

In reality, we’re 90 years too late to take the short boat crossing over the River Forth – it was stopped in 1935, when a new footbridge was built.

We do save ourselves the halfpenny ferry fare, though, and get to cross the bridge for nothing.

The beautiful Cambuskenneth Abbey was founded in the year 1140, and most of the surviving structure dates back to the 1200s.

Visitors standing on its lush grounds in 1919, surrounded by hills and farmland, were likely treated to a very similar, tranquil experience as we are 106 years later.

Shearer’s guide mentions a “good view” from the Abbey’s tower, which tourists in 1919 would have had to pay twopence to see.

Entry to the Abbey is now free, but only the ground floor is open to the public, between April 1 and September 30.

Alas, Isla and I are there too early in the year to go inside.

We discuss cheering ourselves up with lunch or a pint at the nearby inn mentioned in the guide, but the former Abbey Inn has been closed for at least 10 years, and is now residential housing.

Causewayhead by tram

In 1919, some areas of Stirling were served by a tramway, with both horse-drawn and petrol-powered trams.

The tourist guide from that time suggests Isla and I should walk back to the city centre, then pay twopence to travel by tram from Barnton Street to Causewayhead.

Unfortunately, the Stirling and Bridge of Allan Tramway was closed the following year, in May 1920, after 46 years.

Modern adventurers can take the number 52 or UniLink buses instead, which cover virtually the same route and take around 10 minutes, though the short trip will cost them £6.25.

Abbey Craig and Wallace Monument

Obviously, no visit to Stirling would be complete without seeing the National Wallace Monument up close.

From Causewayhead, we make our way along the wooded trails of the atmospheric Abbey Craig.

On foot, this journey is unlikely to have changed much in 106 years, though there is also now a free shuttle bus service available.

In 1919, admission to the Wallace Monument cost twopence. In 2025, adults pay £11.30.

But, much like the vista from the castle, while Stirling’s skyline may have evolved, I’m convinced the view from the top of the monument is every bit as breath-taking today as it was a century ago.

The “food, teas and temperance refreshments” promised in Shearer’s guide at this juncture are still available, thanks to on-site cafe, Legends at the Monument.

And while the advertised inn and temperance restaurant in Causewayhead village don’t seem to have stood the test of time, local institution Corrieri’s cafe is close-by.

At the end of our expedition, Shearer’s guide instructs us to return to Stirling city centre by tram – and we really wish we could.

Hey, Stirling Council, is it time to bring them back?

- University of Stirling’s 900 years of the burgh of Stirling exhibition runs until May 18 and is free to visit

For more Stirling news and features visit our page or join us on Facebook

Conversation