Simon Young is the editor of Magical Folk: British & Irish Fairies – 500 AD to the Present, the first history of fairy sightings in Britain and Ireland over a millennium and a half. He discovered some pretty harrowing stuff…

Fairies have become an intrinsic part of the Christmas spirit. Many families place a fairy on top of the Christmas tree. Fairy lights are everywhere in December. Then, there are Santa’s elves, the stars of so many Christmas films and stories on our televisions and in our children’s books.

But is it really safe to invite British fairies into your home? This is the question I found myself asking while writing Magical Folk, a history of fairy sightings in Britain from Roman times to the present.

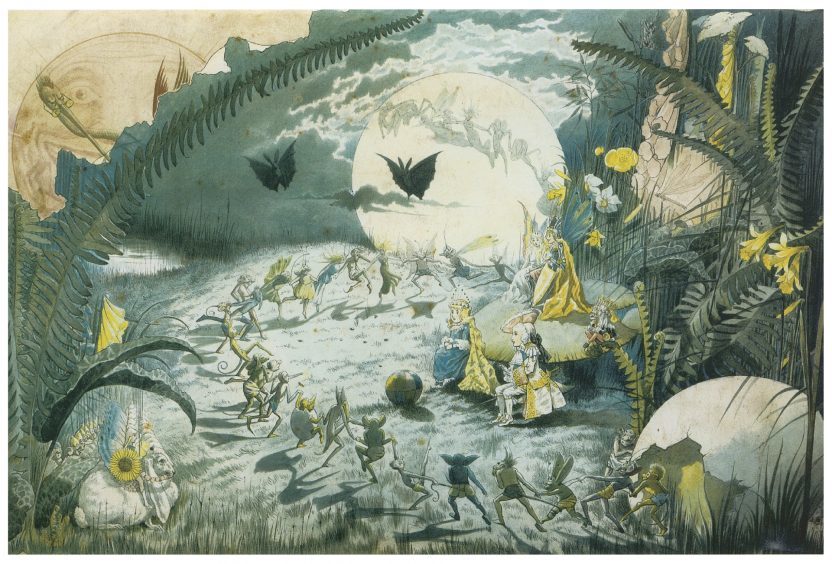

While some are benevolent, many of the magical folk Brits have encountered over the centuries are nothing like Hollywood’s tutu-clad, butterfly-winged miniature Marilyn Monroes meet JM Barrie’s Tinker Bells.

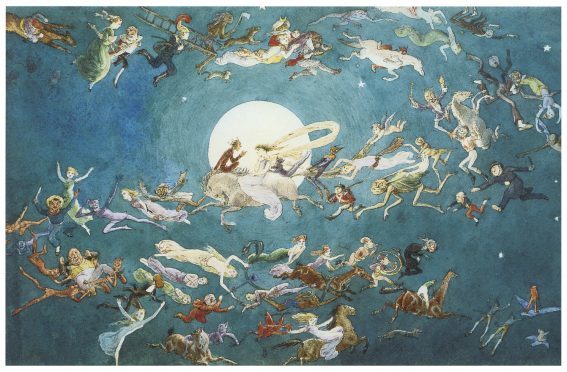

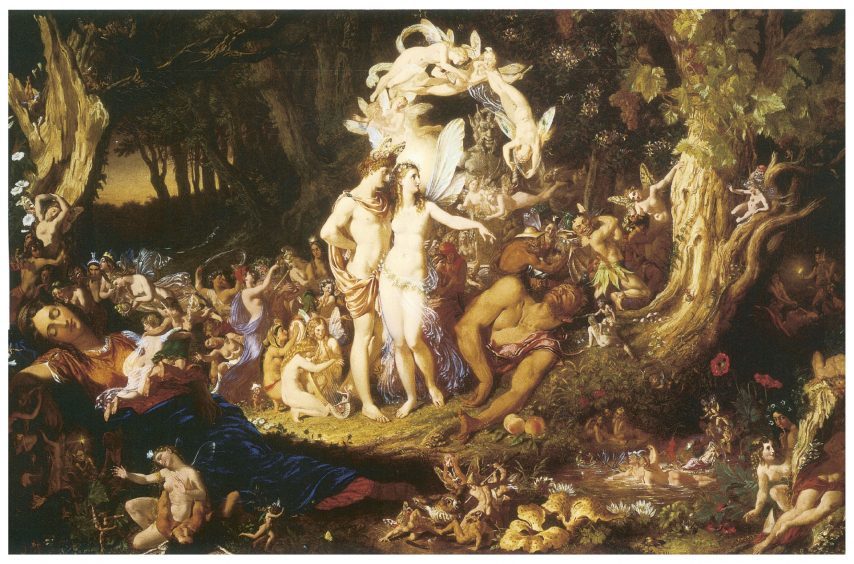

For one, the first British fairies with wings turn up only at the end of the 18th Century in paintings. It was artists who imagined them rather than ordinary folk who encountered them. Among the population there were many vivid superstitions following these sightings.

Many of those who over the past centuries encountered fairies report that in Britain they can be a scary lot. British fairies have a particularly long history of pilfering food from the natives. If they were to get into your home they would likely feast on your Christmas goodies. They are also known to be accomplished thieves, mainly of cattle. But I still wouldn’t count on them leaving any gifts left under the tree as they will have ransacked them.

In fact, a British fairy would probably take a very dim view of your Christmas tree in any case. Fairies have for centuries been associated with trees in the UK, particularly oaks, which fairies loved to dance around.

But they did not stand on top of them to pirouette. They guarded them against humans and walloped those who damaged their charges. Some farmers who sawed branches off a fairy oak near London in the 1600s had their limbs removed by the oak’s irate fairy. It doesn’t bear thinking what they might do when they find not just a branch but a whole tree in your living room.

If you heard all these goings in the middle of the night and were to come downstairs and protest as they revel around your Christmas tree, they might shoot you with an elf bolt. There are many reports of humans being punished harshly by them for interrupting or even watching fairy knees-ups. They don’t like to be seen by humans.

Can it get any scarier? Yes it can. British fairies very possibly would kidnap your children – historical sightings regularly report they flew off with the souls of the young and replaced them with changelings. The history of British fairies reads like a thriller.

Nor would your spouse necessarily be safe. In 1894 in Tipperary, a 26-year-old wife was replaced by a fairy changeling. At least, that is what her husband and his family claimed.

You may well wonder, how did this lively lot become part of our Christmas traditions?

The answer is from the theatre and through the arts. British fairy madness kicked off the best part of two centuries ago on the stage when the grand urban houses ran pantomimes with large numbers of ‘fairies’: troupes of dancing and sometimes flying girls.

These actresses and dancers were winged, dressed in white and occasionally had portable battery-powered electric bulbs attached to their heads or skirts.

The theatre had picked up on the millennium-old association of fairies with glowing lights. Though these fairy lights, as opposed to their electric cousins, misled humans at night. The fairies sometimes tricked their terrified victims into mires and swamps around Britain’s moors and wetlands.

In the theatre the electric lights illuminated thighs rather than trickery. With an unusual amount of innocent Christmas flesh showing theatre-goers took increasing pleasure in watching humans perform as fairies. And this branded the fairy image into the minds of future generations of excitable theatre-goers. So much so that there was much concern in the press about fairy immorality.

Santa’s elves are another set of wolves in sheeps’ clothes. They are the perfumed, jollified version of the terrifying soul-stealing trolls the Vikings talked about. Needless to say, the Viking originals were more likely to eat children, than spend their time wrapping presents ‘for good boys and girls’.

Writers started bowdlerising this rowdy lot of Scandinavian tourists around the same time as electrical lights turned up. Santa and his elves began to appear tapping away with hammer in poems, stories. Then, later they turned up in paintings and, by 1932, in cartoons and performances with fairy ballerinas.

So yes, it is entirely safe to put a charming Hollywood fairy on your tree, decorate your home with electric lights. But if you do spot a real British fairy, firmly close the shutters and stay inside to avoid what could turn out to be a hairy evening.

Magical Folk: British & Irish Fairies – 500 AD to the Present by Simon Young and Ceri Houlbrook (Gibson Square, hardback £16.99) bit.ly/britishfairies

Simon Young is also conducting an online survey into modern fairy sightings, The Fairy Census, which has so far had more than 1000 responses.