Michael Alexander speaks to Fife birdwatcher Norman Elkins about his lifelong interest in ornithology.

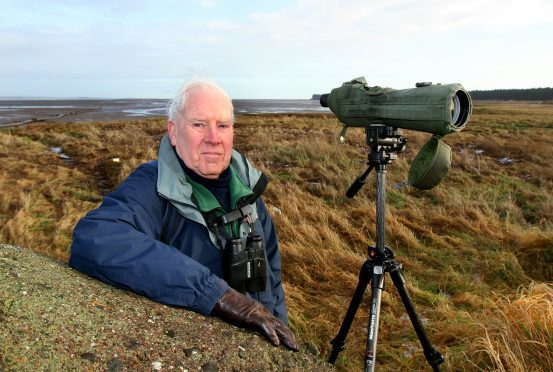

As the British Trust for Ornithology regional representative for Fife and Kinross, the main task for retired RAF Leuchars weather forecaster Norman Elkins is to organise volunteers to take part in the regional component of national bird surveys.

But while the 77-year-old, who lives in Cupar, might spend hours counting some of the 15,000 waders wintering at the Tay and Eden estuaries at this time of year, don’t expect to find him perched in a bird hide.

“I don’t use hides myself,” he says ahead of a trip to the foreshore at Tayport.

“Some people do but I don’t like hides – there’s no point sitting in hides because you are not able to take part in the survey.

“It’s a matter of going into the area where you are surveying and counting birds in that area – you get an eye for it over time.”

Born in Hampshire, Norman, who first became interested in birds as a small boy, worked as a Met office weather forecaster for 42 years, finishing his career at RAF Leuchars where he was based from 1986 to 2001.

Since 1987, he has been responsible for coordinating the team that count coastal birds from the Firth of Tay down to the Eden estuary at high tide when wading birds roost at certain points along the shore awaiting the receding tide so that they can resume feeding on the tidal flats.

All birds are counted monthly between September and April with some counts continuing through the summer.

Then every five or six years, a much larger team counts all birds feeding at low tide, coordinated monthly from November to February.

The main aim of these is to identify those sections of the estuaries that are most important for each species, so that any detrimental effects of developments, whether industrial, agricultural or recreational, can be controlled.

When the organisation published its bird atlas in 2016, it was estimated that there were something like 400,000 to 500,000 pairs of birds breeding in Fife during summer – rising to just under a million during winter when migratory geese arrive.

But the historical data, going back to the 1960s, also throws up trends – good and bad – about the impact of changing environments.

He adds: “I think climate change has a role in the effect it has on bird populations. Sometimes it’s not easy to separate various aspects of this.

“But over the years we do see changes in local bird populations some of which can be attributed to climate change.

“One of those that springs to mind is some species that come here in winter are declining because of the warming of the parts of the world where they breed and also where they fly over when they are on their way.

“For example, birds breeding in the Arctic – if they can shorten their distance from breeding to wintering grounds, they will do.

“We are seeing the effects of this on some ducks that now winter more in the Baltic than come here.

“That’s just one instance.

“If the breeding grounds stay open for longer time they will hold off before they come. “It’s all a matter of do they have enough food? If the food dwindles quickly in the autumn then they’ll move away and come here.”

It’s the varied lifestyles of birds that Norman finds so appealing.

He adds: “I suppose it’s the fact they are easily seen, many of them are very handsome looking creatures; they have fascinating lifestyles. Sparrows for example stay here all year round and you’ll get birds that will travel from the Arctic to Southern Africa for the winter and back again.

“It’s a matter of what bird you are looking at. You know it’s life history or you know part of its life history and it’s just fascinating to think about that.”