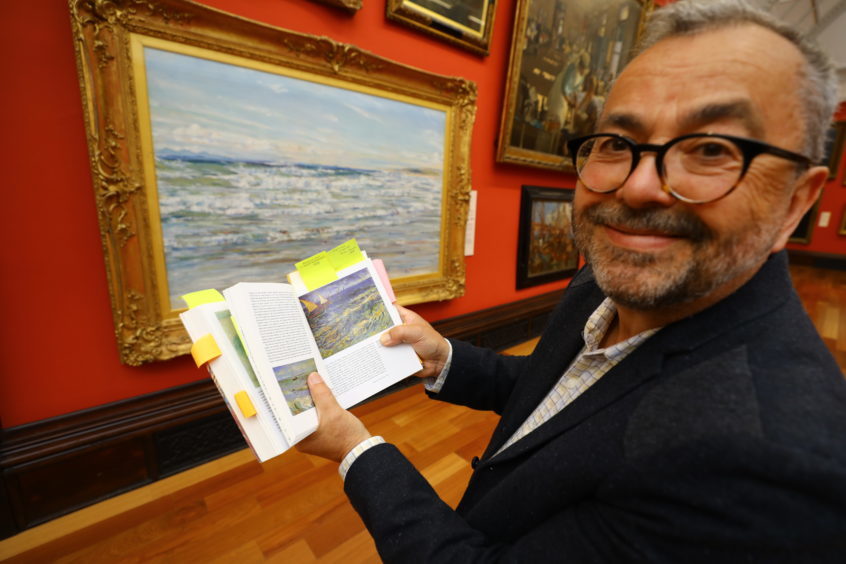

Author Ralph Skea hopes his latest book will shed new light on Vincent van Gogh’s paintings and his enigmatic personality. By Caroline Lindsay

On his 12th birthday, Ralph Skea’s aunt bought him a small book on the artist Vincent van Gogh.

“It was the first time I had seen a collection of his paintings and they seemed so unusual,” says author Ralph, who lives in Perthshire.

“This little book (that I still have) stimulated my interest in Van Gogh’s paintings in my teenage years, further fuelled by books borrowed from Arbroath public library,” he recalls. “The book acted as a stimulus for a lifelong interest in his work and demonstrated how a childhood event can influence someone’s later interests.”

Today Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Van Gogh (1853-1890) is regarded as one of the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In just over a decade he created more than 2,000 artworks, most of them in the last two years of his life. Ralph, 70, has published several books on the artist who made such an impression in his formative years.

“In 1967, when I was 19, I bought a book containing a selection of his letters which revealed what a complex personality he was,” he says. “Visits to see his paintings in galleries all over the world inspired me to write a series of books which would analyse his work in new ways.”

The artist’s main collections are in the Netherlands, including the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, while major exhibitions in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and London have helped Ralph’s understanding of Van Gogh.

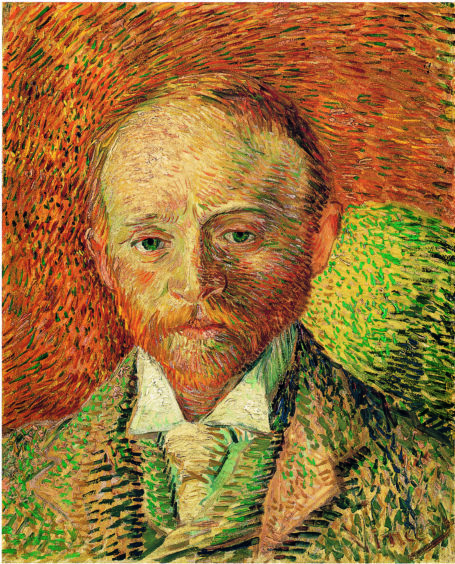

Ralph’s latest book, Vincent’s Portraits, includes Head of a Peasant Woman in a White Cap from the collection of the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, while Portrait of Alexander Reid hangs in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

“Reid was an art dealer from Glasgow, working in Paris, when he became friendly with Van Gogh,” Ralph explains. Vincent’s Portraits is the third in a series devoted to the celebrated artist’s life and work.

“The first two focus on his paintings of nature but this book deals with his depictions of the kinds of people he encountered in the Netherlands and France,” says Ralph.

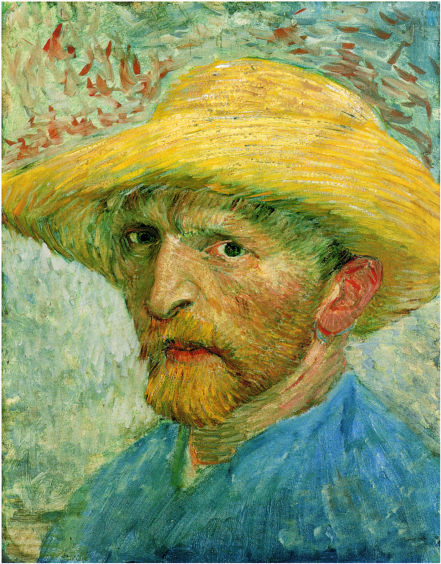

“All three books use Vincent rather than Van Gogh in their titles and throughout much of the text because he always signed his work ‘Vincent’, as he believed nobody would be able to pronounce his surname correctly. In France he was known always as Vincent or Monsieur Vincent.”

The book is structured around the main locations where Van Gogh settled and painted his portraits of various models: farm workers, urban poor, people in cafés, friends, fellow artists, doctors, postal workers and so on.

“He wanted to present the range of people in his paintings that contemporary novelists also wrote about,” says Ralph.

He believes that Van Gogh was a totally committed, intuitive artist and obsessively productive.

“I admire that, as a self-taught artist, he achieved so much in such a short career between 1880 and 1890. His huge output – 900 paintings, and 1,100 drawings – was of a very high quality and is now famous throughout the world.

“I also admire that he was so focused on his own perceptions of his surroundings but was always interested in the new ideas that his artist friends discussed with him – and this led to experimentation regarding colour and composition,” he continues.

“Like many great artists and writers he was enigmatic – a lonely man who forged strong friendships; prone to depression yet enthusiastic; lacking in confidence yet supremely talented; often hypomanic yet an intellectual, well read, and fluent in Dutch, French and English.”

Van Gogh had trained as a missionary and curate before turning to art and this, says Ralph, is reflected in some of his work.

“In some respects he was a ‘religious’ artist, but one who had lost his Christian faith,” he observes.

Revealing in a letter: “It gives me air when I make a painting,” Van Gogh showed symptoms throughout his life of being what would now be called bipolar and was hospitalised on several occasions. But this affliction didn’t prevent him from painting.

“His infamous self-mutilation when he cut off his own ear was the result of this and, latterly, he was an artist who experienced an illness that was increasingly debilitating,” explains Ralph.

Tragically, on July 27 1890, Van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a revolver and died from his injuries two days later.

Regarded in his lifetime by many as a madman and a failure, it was only after his death that he became famous as a misunderstood genius.

Ralph explains that because Van Gogh spent half of his career in France – mostly in Paris and the south – his work combines aspects of Dutch and French pictorial art. Ralph explains why this is. “In Holland and France he painted in many different styles – his work completed during the first five years was based on 17th Century Dutch artists like Rembrandt and Frans Hals, his own Dutch contemporaries, and the French artist Millet,” he says.

“In Paris and the south of France he experimented with Impressionism. He was an eclectic painter, borrowing styles and integrating them in various paintings.

“What makes his work so recognisable, despite this varied approach, is that he fused drawing and painting together, giving his images a powerful graphic quality.”

Ralph believes that paradoxically, Van Gogh was both ‘of his time’ yet totally unique in his approach and imagery.

“For some historians of art his work is classed as ‘expressionistic’ – the result of an artist’s strong personal feelings regarding his subject matter. Certainly, people seem to respond to his work on an emotional level.”

Ask people to name a painting by Van Gogh and chances are they’ll say “Sunflowers”. But, Ralph reveals, the artist painted a number of sunflower works, all variations on the same theme.

“He felt that the image was essentially simple and consoling – and this may be why people relate to the painting,” he muses. “Also he used strong outlines to define leaves, flower heads and petals, giving it a bold graphic quality that lends its power as an image. And it is quite a large image – impressive on the gallery wall.

“Interestingly he felt that people would identify the sunflower with his achievement as an artist and in a letter to his brother Theo, an art dealer based in Paris, he wrote: ‘the sunflower is mine, in a way.’”

Letter writing was important to Van Gogh and the 819 letters that survive show that he was one of a few famous visual artists who also wrote great literature.

“Although most were sent to his brother, an important number were received by his sister Wil; also, he corresponded with his friends, the French artist Émile Bernard, and the Dutch painter Van Rappard,” says Ralph. “Although they all deal with his very perceptive views on painting techniques and colour, they also cover a wide range of topics related to contemporary society.

“His powers of description – related to landscape, flowers, gardens, climate, people – were formidable and his prose style is widely admired.

Most of the letters also describe and analyse the books he was reading and a huge number of novels are discussed.

“Overall, the letters demonstrate that Van Gogh was an intellectual and a fine writer rather than the uncouth outcast of legend.”

Ralph hopes his latest book will help readers see Van Gogh in a new light.

“Although he is so famous, many people may have preconceptions as regards his paintings, drawings and personality,” he reflects. “Hopefully the range of images and quotes from his letters will give readers a fuller understanding of this great artist and the times he lived in.”

Vincent’s Portraits by Ralph Skea is published by Thames & Hudson, £12.95.