A Perthshire stonecarver is keeping an ancient skill alive and, as Caroline Lindsay discovers, has created two Egyptian cartouches.

If our main feature on page 4 has inspired you to head to the new Ancient Egypt galleries at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS), make sure you look out for two unique cartouches created by Perthshire stonecarver Gillian Forbes when you’re there.

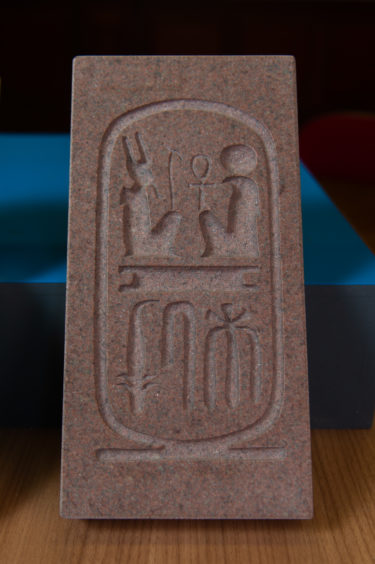

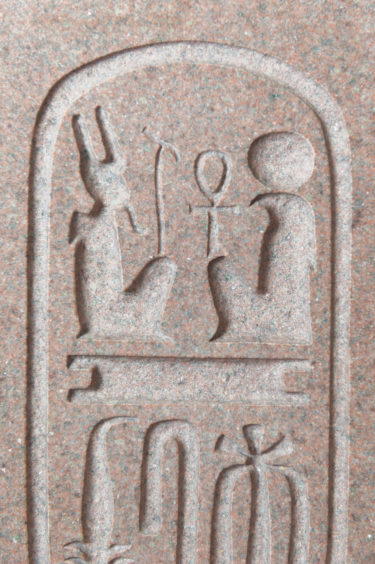

These engraved stones, just over a foot in height, have been specifically created as “touch objects” in the exhibition, for visitors to touch and explore.

The opening of the two new galleries at NMS yesterday, devoted to ancient Egypt and East Asia, marks the completion of a 15-year, £80m masterplan to transform the museum. Gillian was commissioned by the museum to carve the two ancient Egyptian cartouches.

Using red granite for one and hard creamy limestone for the other, Gillian muses: “It was so interesting interpreting the available information in my chosen stones. Like everyone else, I can’t understand how the Egyptians worked granite and other hard stones with their available tools.”

Cartouches were used to write ancient Egyptian royal names and the hieroglyphs of the name are encircled in a ring symbolising eternity.

“The red granite panel is carved with sunken hieroglyphics while the limestone one is carved in relief,” says Gillian, who has worked in stone since 1990, with the aim of developing the craft of hand carving in Scotland.

“I’m based at my purpose-built studio in the hamlet of Path of Condie in the Ochil Hills, and here I create bespoke stone carvings predominantly from British slate, sandstone and limestone,” she says.

She has also worked on public art commissions since 1995, including the Canongate Wall in Edinburgh and Perth’s Flood Prevention Scheme.

In addition, she has created numerous smaller commissions including her personal favourites: one of the lions at the entrance gates to Glamis Castle and some marble hands that she made in Italy.

Thrilled to be a part of living history, Gillian explains that NMS advised her that the purpose of touch objects is two-fold. “Firstly, to compare raised and sunk relief stone carving. In ancient Egypt, the former was used indoors, while the latter was used outdoors,” she says.

Secondly, the idea is to compare carved soft stone and hard stone.

“The former was fairly easy to carve for intricate raised relief, while the latter was laborious to carve,” she explains.

“Ancient Egyptians used sunk relief carving outdoors. In bright sunlight, the deeply cut lines created shadows to emphasise outlines.

“Indoors, in dimmer light, more delicate details could be produced by using raised relief and this required carving away the entire background,” she says.

Gillian’s passion for stone started at Glasgow School of Art after researching 18th Century Scottish headstones.

“If you take into account the fact that they had little knowledge of the outside world and yet still created beautiful, inventive carvings then that is a feat in itself,” she marvels.

Continuing her education at Weymouth College in Dorset where she developed the techniques of shaping and building with stone, she says: “The inspiration for my carving is drawn mostly from the natural world, and it was this interest in plant and animal forms which led me to establish my business in 1995.”

Also inspired by contemporary European sculptors and Egyptian carvers, Gillian likes to work with clients who have an understanding of what she does and appreciate that this type of creative work can take a long time.

“No part of the process – from design to sourcing stone to undertaking the work – can be rushed,” she says.

“Being self-employed means I get to choose projects to get involved with and I can spend days cutting letters or just creating designs in stone.”

Describing the tools of her trade, she says: “I have a huge selection of hand tools – chisels, rifflers, rasps and the like, as well as many grinders and other power tools which speed up the work.”

This summer Gillian will be taking on an apprentice this summer and aims to undertake new projects with her, passing on the skills she has learned in her working life so far. It looks as if the ancient art of stonecarving is alive and well.