Michael Alexander speaks to author Sara Sheridan who is looking unflinchingly at Scotland’s heritage to bring women who have been “ignored” by history to light – including Dundee missionary Mary Slessor.

Sara Sheridan is feeling angry.

Not in a “I want to punch someone” sort of way.

It’s more a case of every time she walks down George Street in Edinburgh, the presence of countless male statues reminds her that for most of recorded history, women have been “side lined if not silenced” by men who named the built environment after themselves.

A committed feminist since her teens, Sara, 53, has been fighting for gender equality for years.

But ever since she was commissioned by Historic Environment Scotland in 2018 to “remap our country as if the landscape had been dedicated to the memory of women, rather than men”, she admits she’s been “radicalised” and often feels pent up anger as to why so many successful women through history have been “forgotten”.

Intersection of history and fiction

“It was a really interesting book for me to write,” says Sara, reflecting on the publication in May 2019 of ‘Where are the Women?‘ – a hardback guidebook to an imagined Scotland where the achievements of real Scottish women are commemorated in buildings, monuments, street names and statues.

“It’s like an intersection of creative non-fiction. The Scotland is real, the women are real but all the monuments are made up.

“It’s the sort of thing that would make a real historian wake up in the night worried. That intersection between real history and fiction. But I’m a novelist so I’m used to making things up!” she laughs.

Sara will be launching the paperback edition of the book on March 4 alongside an online Historic Environment Scotland event for Women’s History Month.

She will talk about her guidebook to that “alternative nation”, where the cave on Staffa is named after Malvina rather than Fingal, and Edinburgh’s Arthur’s Seat isn’t Arthur’s, it belongs to St Triduana.

It’s a world where you arrive into Dundee at Slessor Station and the Victorian monument on Stirling’s Abbey Hill interprets national identity not as male warrior William Wallace but through the women who ran hospitals during the First World War.

The West Highland Way ends at Fort Mary, while the Old Lady of Hoy is a prominent Orkney landmark.

The plinths in central Glasgow, meanwhile, proudly display statues of the suffragettes who fought until they won.

“These imagined streets, buildings, statues and monuments are dedicated to real women, telling their often untold or unknown stories,” she says.

But at the same time, she doesn’t expect everyone to agree with what she’s saying.

“When I did events in 2019 there were plenty angry people turning up to support me,” she adds, “but usually you get one old guy up the back saying: ‘yes this is all about women, but why have you cut out the men?’. I’m like ‘yeah it’s a book, imagine if that was your real life!’”

A committed feminist

Named as one of the Saltire Society’s most influential women, past and present, Sara has been writing books about female history of one kind or another for over 20 years.

She is known for the Mirabelle Bevan mysteries, a series of historical novels based on Georgian and Victorian explorers, and has written non-fiction on the early life of Queen Victoria.

Yet within weeks of starting this project she became “furious” as she began uncovering all these women she’d never heard of.

“I was getting crosser and crosser thinking this is absolutely crazy!” she says.

“We’ve got all these amazing stories and we’re not teaching that in schools, we’re not honouring that history.

“Our history is very white and very male. We really need to start challenging that.”

Legacy of history

Sara thinks there are a lot of different cultural and social reasons why so many successful women have been “overlooked” by history.

One of them is that during the late Georgian/early Victorian period it was considered “improper” for women to be in the spotlight. Susan Ferrier, for example, was an amazing writer and was tipped by Sir Walter Scott.

Yet she stopped writing because she didn’t like being recognised as an author. She herself was conditioned to think it was inappropriate for her as a woman.

Another reason, she thinks, is that a lot of women’s achievements are “subsumed into male stories”.

“You get a lot of situations where the man that somebody is married to or somebody’s father or brother was very famous, and they get all the credit,” she says.

“That’s happened several times because it was an easier story or it was considered bad that women were working.

“I think as well because so much of our library culture, artefact culture is curated by men. Men tend to just pick the things that seem familiar to them and seem important to them.

“A good example of that would be suffragette banners. The suffragettes all had banners like these trade union banners that were sewn. When the suffragettes won suffrage, many of these banners were offered to museums. But the curators turned them down. ‘We don’t need this it’s just some women’s thing’, they’d say.”

Legacy of Dundee’s Mary Slessor

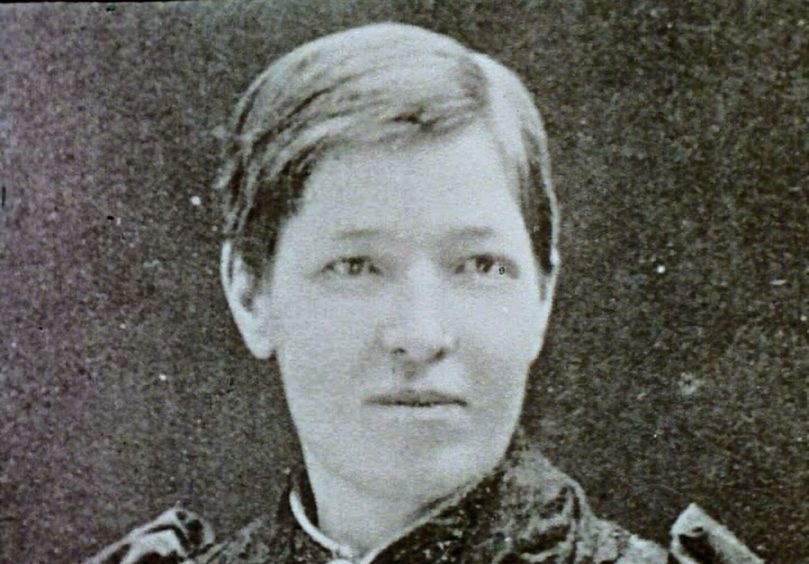

Sara is aware that the Presbyterian missionary Mary Slessor is synonymous with Dundee.

However, had Mary Slessor been a man, she’s convinced her achievements would have been as well known as explorer David Livingstone who has statues in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and who arguably didn’t achieve as much as Slessor.

“Dundee is quite interesting as well because one of the things I discovered when I was writing the book is that our built heritage really sort of outlines the way that people will achieve,” she says.

“In Dundee, for example, there was kind of a rash of late Georgian or mid-Georgian poets – female poets – who were all working class.

“They were very well known in their day. You look at that and that didn’t really happen anywhere else in the country.

“Then you start to look at Dundee at that time and you realise the factories were starting up, women were getting employed and had money. They could put money into backing pamphlets and there were other women who would buy those pamphlets.

“There was no such thing as a publisher in those days. You published a pamphlet and people subscribed to it. A bit like a podcast today!

“That’s why that happened in Dundee. The actual environment in which the women were around meant that in Glasgow you had a lot of labour activists because you had a lot of factories.

“Or in Edinburgh you had a whole load of dramatists because this is where the main part of the theatre was based. Those poets in Dundee might have gone on to be labour activists if they had been living in Glasgow at the right time.”

Eliza Wigham

Asked if any particular women she didn’t know about stand-out, Sara says there are “quite a few”.

One that really surprised her was Eliza Wigham – an Edinburgh-based Quaker and anti-slavery campaigner.

The Victorian was described as one of six key women in the British Trans-Atlantic Anti-Slavery Sisterhood. She campaigned to free indentured workers in the US after slavery had been banned.

Sara says the “great news” to come from her book is the knowledge that our grannies, great grannies and great great grannies’ generations were “amazing”. It’s all our heritage – male and female.

Yet despite awareness being raised, and women making up over 50% of the population, she still feels the issues are so “deeply embedded” in culture and society that it will make much more effort for equality and openness to be “normalised”.

Comparable to Black Lives Matter?

Sara’s book was written before the #BlackLivesMatter movement highlighted the “inappropriate” nature of some statues and street names in our cities that commemorate slavers.

Inevitably, the gender issue raises similar questions about how we commemorate women. Should some male statues be placed in museums and replaced?

It’s an argument that also applies to black and LGBTQ communities, she says, and the diversity of communities and our collective history “really needs to be looked at.”

“I think about me as a kid growing up in Edinburgh, what a difference it would have made if I’m walking down George Street with my brother and he sees six statues of men who look like him and I’m walking and I don’t see any who look like me.

“What you’re telling your daughters is your achievement isn’t possible or doesn’t matter. If they do do something, they think they are the first because previous generations of women weren’t memorialised.

“Children need to know they come from a broad spectrum of achievement to be able to reach their potential. If we do this for anyone, we do this for the kids.”

*For details about the Historic Environment Scotland online event on March 4, go to