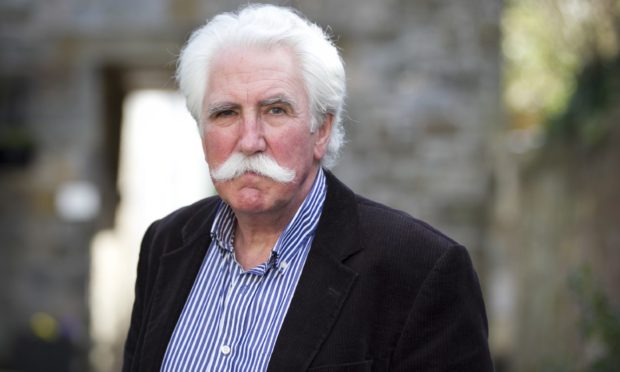

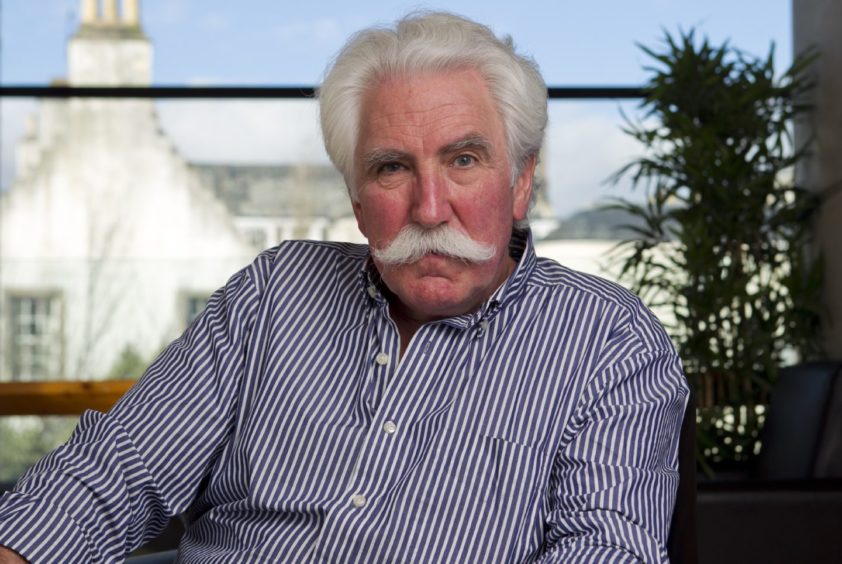

A short exchange of emails with poet Brian Johnstone back in February inquired if I might like to review his new collection, The Marks on the Map,and ended cryptically: “tho’ I’m not in the best of health…so we’ll see”, Jim Crumley writes.

The book arrived in late March. I was so taken with it that I thought I’d like to write more than a review, but in the time between sending it and its publication, Brian died, and Scottish poetry is in mourning.

I struggled to write a brief word of tribute, and found a better one instead within Brian’s book, in a poem called A Late Gainsborough: “a journeyman of landscapes to the last”. Nice one Brian, and thanks for the book.

And here, before Brian died, is the piece I wrote:

Have you ever get lost in a slim volume of poetry, so lost that when you reached the end you decided to re-trace your steps and read your way backwards through the book to the beginning again?

Then, back at the beginning of the first poem, you find your own world waiting where you left it before your immersion in the poet’s world, or at least in that portion of it the poet has chosen to share with you.

Your decision then is whether to step away from the poet’s landscape and reacquaint yourself with the workaday, or perhaps extend your stay a little longer, pausing here and there at those marks on the book’s map where you lingered most fondly.

All this takes days, of course, or weeks. But one day, perhaps you flick through the preliminary pages that precede the first poem and you find something that had been there all the time and you’d never noticed. It is a quotation from Hermann Hesse.

I know Hesse. No, that’s not true, I know one of his books quite well; it’s called Wandering. His presence here in someone else’s poetry book makes sense. The quotation is this:

“One never reaches home, but wherever friendly paths intersect the whole world looks like home for a while.”

That idea summarises perfectly the reason I lost myself in a new collection of poems by Fife-based poet Brian Johnstone, The Marks on the Map.

It also offers a kind of shorthand account of everything that follows, the intersections of friendly paths that permit you to get lost while feeling at home, paths like this one, from a poem called Primrose (Primrose is an abandoned house at Kenly Den near Boarhills):

We found the way, grass-grown in early summer,

and crossed the burn to scramble up the slope,

push open half a double door ajar for years.

The landscape of The Marks on the Map is intimate, at hand, somehow familiar whether it’s north-east Fife (it often is) or Leith in 1911, or the Bell Rock or the West Highlands, or for that matter, Louis Armstrong’s portentous arrival in Chicago in 1922, beyond which jazz would never be the same again, an event that matters to this particular poet, and to me too.

So the time is yesterday, the septuagenarian poet is looking over his shoulder at some of his own yesterdays and also following intersecting paths that lead to other histories.

The tone is not so much nostalgic as respectful, grateful, the language is quietist (which I like in a poet), precise, spare. He is very good at atmospheres, which is why you get lost in his landscapes so readily.

The first poem, A Back Street in Leith, 1911, is about a photograph of a tenement with the windows open and a curtain flapping in the wind:

At the foot of the half-raised sash

the fresh breeze of an age

that’s barely past slips over the sill.

Not hard to imagine the notes it carries

– a whiff of horses,

coal smoke, the sea a street away –

We’re the same generation, the poet and I, which also assists me with identifying some of the marks on the book’s map; we remember people whose young years inhabited just such a photograph of just such a tenement, his Leith, my Dundee.

His poem, Heritance, inhabits his grandmother’s house:

I can open your door, if I think back

far enough, walk down your dim-lit hallway

by the grandfather clock that gave me the creeps…

and you can see that clock, twice as tall as the bairn, carved wood, and it never stopped its four-in-the-bar chatter.

That’s another thing: this poet likes jazz and it shows, likes to perform his poetry with his own jazz trio called Verso, so it’s no surprise to me, a sometimes jazz player myself, that the lines are rhythmical. This is poetry that swings. You can click your fingers to it, tap your feet.

I tried reading bits of it to the accompaniment of a jazz duo album called Afterglow, Enrico Pieranunzi (piano) and Bert Joris (trumpet and flugelhorn), an Italian and a Belgian.

The international language of jazz is the trick Esperanto never quite managed to pull off, and it never missed a beat when it met the Scots poet head-on. As I read aloud but softly to myself, somewhere down one particular album track and one particular poem the inevitable happened and the rhythm of poem and music coincided perfectly, fitting one on top of the other.

Old hidden buildings in east Fife and paths leading to them are a recurring theme. One such is Outfield where,

…your father

steered his tractor up to trailer down

the coffin of the old man, last

to call it home.

Another is A Cart Road whose landscape is by the Eden:

…a pack horse bridge leads nowhere now,

the river having quit the beaten track.

And yet another is The Old Straight Track:

…defying all attempts

to ever organise, corral the footsteps

of a freedom never lost, but in us all.

There is another quotation at the beginning of the book beside Hermann Hesse, from Alexander McCall Smith: “Regular maps have few surprises. More precious, though, are the unpublished maps we make ourselves; those maps of our personal memories that make the private tapestry of our lives.”

The nature of the poet’s craft

For all of us who are thirled to this tract of eastmost Scotland, our private memories are enriched by the visible imprint of history, so that the past creeps into our present whether we like it or not. Two poems take that idea and reshape them in ways you might never have contemplated before, for such is the nature of this poet’s craft.

Mr Stevenson’s Landfall on the Bell Rock illuminates the rock before the lighthouse maestro and grandfather of Robert Louis Stevenson began to build, sifts among the scraps of wreckages the sea had not dislodged: not just

…the anchor shaft,

the crowbars, locks and chain of craft that plied

a fatal course…”

but also the unexpected souvenirs,

possessions whose possessor must have clung on

to the rock as hope receded fast. These tokens found

men detailed in the log…and last,

examined as they fathomed what it was, its owner

likely overcome by tide, a buckle from a shoe long lost.

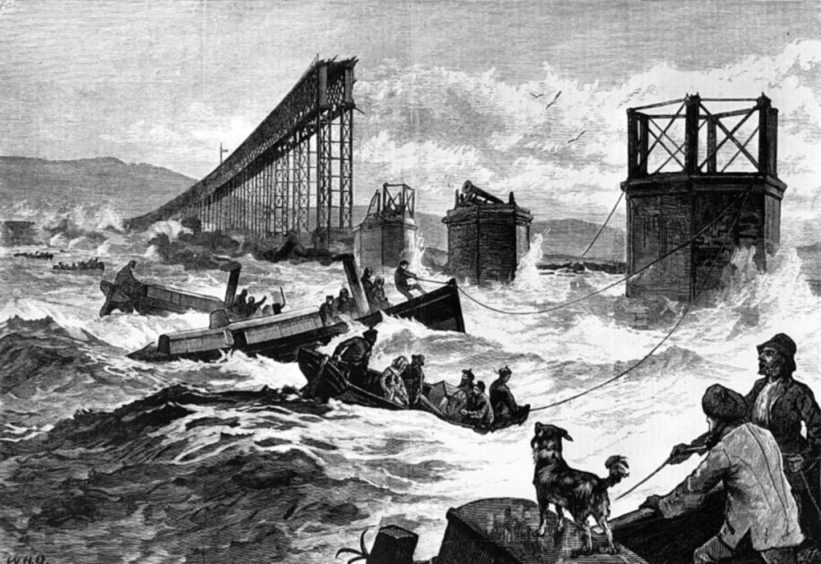

No less notorious , no less conspicuous to us of the 21st Century every ebb of the tide, the Tay Bridge Disaster is held fast with this pointed slant in the poem, The Last Train from St Fort:

…the locomotive, not yet renamed The Diver

as it would be later, hauled out of the deep,

uncoupled from its ruined rolling stock

to ride the rails another day.

The Diver? Even now, you catch yourself smiling at that ever-so-slightly sick joke, wondering who came up with it and wondering what part they might have fulfilled in the aftermath. But we must all make our own accommodations with the marks on the map of our lives.

What would you have done if you had seen the train go down, or found the shoe buckle on the Bell Rock?

And one way or another, we all still live with such aftermaths.

Finally, the title poem, The Marks on the Map, is a prose-poem tribute to a tramp. The marks on his particular map were the back doors of the big houses he chapped on, seeking a bit of work, a bite to eat, a shakedown in a barn; and this is his matter-of-fact philosophy about how he is received by the inhabitants:

…each one a species

of kindness or scorn, a foot put in front of another.

The jazz coincidence happened again. The poem, A Lock of Fleece, begins, Strangers to the church… I began to read as the music laid down the opening theme of How Could We Forget, and it fitted, syllable for syllable.

So I was just wondering if you ever get lost within the covers of a slim volume of poetry, so that, for example, you find quiet backwater landscapes, old pantiled cottages, a time of life and the view that particular time imposes on the things that matter and pays respect to them, a muted watercolour language and an optional soundtrack of jazz.

And all these conspire to make you wonder why you don’t spend more time getting so agreeably lost.

- Brian Johnstone was an internationally acclaimed poet and a founder of the StAnza festival, Scotland’s poetry festival in St Andrews.

- The Marks on the Map by Brian Johnstone is published by Arc Publications, www.arcpublications.co.uk