It takes a particularly strong frame of mind to write about a subject that seems to be in terminal decline — but that is what makes Aeneas Macdonald’s book, Whisky, so fascinating. It was written in 1930 when the fortunes of Scotch whisky were at their all-time nadir.

During the First World War, heavy excise duties and US prohibition had brought the once-thriving industry to its knees. Scores of distilleries had been mothballed or closed, most of them never to reopen.

In addition, whisky was then a subject to be avoided in Scotland, as in those deep Depression days it was seen as the drink of the desperate, the poor and unemployed — a deceptive solace for their sorrows that would only make them worse.

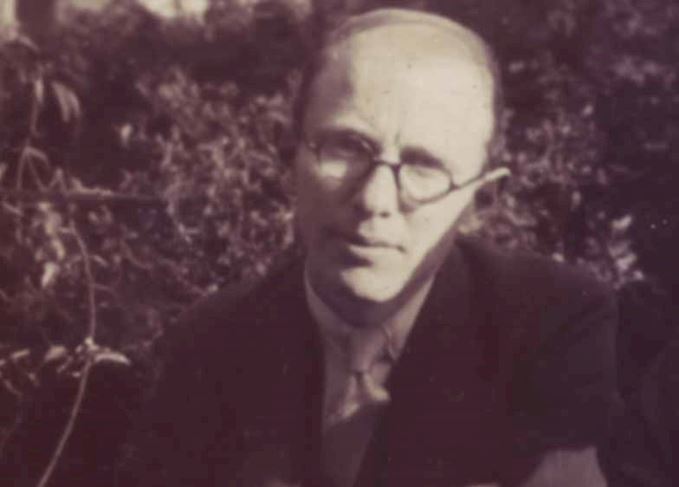

The book was actually written by a noted Scots journalist, George Malcolm Thomson, who wrote it under a pseudonym as his mother was rabidly teetotal and would have been appalled at her son’s perceived treachery. Today, easily a dozen new titles on or linked to whisky are published every year, but Whisky was probably the first whisky book, written for the public rather than those in the industry, to appear in the UK in the 20th Century.

It was no galloping best seller, although there were reprints, including one in the US after the end of Prohibition. Now Scottish publishers Birlinn have re-issued it in hardback, with an informative commentary and footnotes by whisky author Ian Buxton, and I found it fascinating. It is not the easiest of reads, as it ranges from factual reporting to polemical essay, often within the same page or even paragraph. But he knows his subject and its history, although he rarely sets his ideas down in the neat, logical order we tend to expect today in non-fiction.

He also has strong views. Single malts are praised — at a time when few drank or appreciated them — and blended whiskies often excoriated as dire potions that drove those who drank them to stupor and early oblivion. He is often scathing of wine drinking (wine then was starting to be drunk by Scottish middle and professional classes after decades as an upper-class tipple), claiming merchants were unloading third-class wines with sneaky labelling onto gullible poseurs who wouldn’t know a grand cru from the direst plonk.

However, what the book has in abundance is passion, for whisky, for its history, for the sheer enjoyment of a good dram in good company at the end of a long, weary day. It is a book written before its time but it may unwittingly have sown the seeds of today’s global passion for Scotch whisky and single malts.

For that reason alone, it’s worth reading.