Having described the effects of US Prohibition, both on America and the wider world, it is only proper to say the temperance movement a century ago was not solely a US phenomenon. In December 1920 Scotland held local referendums on outlawing alcohol and many places voted “dry” and closed their pubs and off-licences, many for decades.

So how did this come about? The UK temperance movement grew throughout the 19th Century when working class poverty, bad housing and other social ills coincided with cheap drink. In the 1890s, a gill of raw whisky in a Glasgow pub was sixpence or less (2p). A bottle of good whisky was about two-and-sixpence, or 12-13p. Pay was low (£2 a week was good money) and, sadly, many men squandered much of their payday envelope in the pub.

Their wives and children suffered, drink was widely seen as the root of all evil. This spawned the temperance movement, supported by women’s groups and the kirk, who campaigned for restricted pub hours, higher taxes and, often, a total ban.

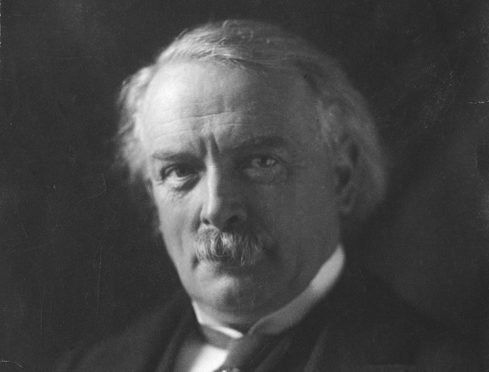

They had some success. Temperance establishments opened and in 1909 then-Chancellor David Lloyd-George (pictured) hiked alcohol duties, near-doubling them on spirits, hitting the whisky industry hard. Then in 1912, all whiskies had to be matured for at least three years, a rule that still applies today.

The First World War led to more problems. Poor initial wartime output – largely due to bad planning and management – was politically blamed on workers drinking, so pub opening times were slashed, taxes raised again and spirit strengths cut. With barley needed to feed humans and army horses, supplies to distillers dried up. In 1915 King George V pledged abstinence until Victory Day and urged everyone to do the same.

After the Armistice in 1918, problems continued. Hero soldiers returned to no jobs, Spanish flu ravaged Europe, spirit duties rose again and a dark post-war anti-drink mood gripped the UK.

The 1920 referendums were held in 584 of Scotland’s 1200 licensing districts, with 60% voting for “no change”, 38% for strong restrictions and some 40 areas for an outright ban. Most of these were around Glasgow and in Ayrshire, although Lerwick went dry until 1947. Last holdout was Kilmacolm, which finally got a pub again in 1996.