Catherine Devaney, a regular columnist for The Courier’s food and drink magazine The Menu, finds calmness in an unexpected way

The morning of January 1 2020 found me lying on the floor of the bedroom – alone, I should add – attempting to fulfill one of many New Year’s resolutions.

The carpet was a bit scratchy, my back was a bit sore and the unmistakeable melodies of Frozen transmitted through the floorboards. Yet there I was, focused intensely on breathing and visualising something (I can’t remember exactly what now, but it involved a hot air balloon).

Daily meditation practice. I had downloaded the app. I had the book. I was all over the mindfulness thing and 2020 was going to be the year in which I embraced calm, learned not to get swept away by emotions, doused the internal rage and lavished an aura of loving kindness to all who should enter my mindful bubble.

And then the phone rang, thereby highlighting the first flaw of the meditation app – you can’t listen to the “Daily Calm” when the phone is in flight mode. New Year felicitations from Dundee.

As I attempted haughtily to explain to my parents that perhaps we could exchange greetings after the 10-minute window of calm I was attempting to cultivate had passed, I should have realised this was a resolution doomed to failure.

I manfully struggled on with the daily meditation until mid-March, when coronavirus wrenched the lid off my internal anxiety chamber and it no longer seemed relevant or feasible to sit on the bathroom floor for 10 minutes every morning cultivating inner peace.

No, I had far more important things to do, such as voraciously digest every minutiae of news about the crisis in between teaching the five times table and building a boat (home schooling… how I will not miss you).

And then of course there was all that eating to be done. And baking. And roasting and deep frying and proving and bun-making, rolling, whipping and piping. Not for the first time I came to realise that when things got tough I was profoundly incapable of taking care of my own mental health.

All very well to meditate mindfully in the spa on a blissful pre-Covid skiing holiday, but when it might actually have been useful to take action on some of those pesky internal demons I effectively threw my newfound mindfulness tools in the same direction as the spelt and the lentils.

Or did I? Here’s the thing. I used to have a career where I spent a lot of time every day hunched over a desk thinking about things. Really quite hard things much of the time. The mental treadmill was unstoppable. I literally felt like I was chasing endless iterations round a hamster wheel on speed.

And when I wasn’t thinking about the hard things I was talking to people about the hard things, or writing opinions about the hard things, or arguing about why I was right about the hard things. There was room for little else, except the one constant in my life, which has always been cooking.

Because cooking is a set of physical tasks and processes – with a tangible end result – it is the single form of mindfulness that I have managed to practise for as long as I can remember, without even thinking about it.

It engages all the five senses… think about the feeling of a wooden rolling pin in your hands and the pressure as you roll out pastry… the sound of a sharp knife slicing through an onion… the pungent, homely smell of garlic sautéing in bubbling butter, the sizzle of meat hitting a searing hot pan…the green-ness of perfectly cooked asparagus, the red-ness of a juicy strawberry, the stolen tastes both sweet and sour.

Now that I’ve swapped the all-consuming thinking job for an all-consuming doing job (a very physical job, often a bone-wearyingly tiring job), the funny thing is that it’s through all the doing that I’ve finally managed to start thinking clearly.

I’m regularly amazed by what the sub-conscious mind will achieve when it’s released from active thought by the act of physical repetition… whether it’s popping broad beans, segmenting oranges or de-bearding mussels. I’ve never felt so creative.

Perhaps, spending all those years working so hard at all that thinking, I should have tried a little more doing and perhaps the answers would have come to me in their own way.

These days I get up at 5am every Saturday and bake around a hundred scones.

And it is truly the most peaceful part of my week. There was a time, not so long ago, when I would have been in front of my computer at that time of a weekend, but I now do my best thinking somewhere between the third and fourth batch of scones.

Plunging the cutter into the dough, taking care not to twist when I release it, lining them up regimentally on the baking sheets, putting the next batch on to mix as I go.

Last Saturday morning, as the baked scones lined up on the cooling racks, the clock ticked past 6am and the radio played “Love is All You Need” by the Beatles, there was an overwhelming feeling of near elation (it’s that line, “there’s nothing you can do that can’t be done”), but more than that, a sense that my brain was ticking off the answers to all of the problems I’d been grappling with over the course of the week.

And so there it is. You don’t need an app or a book or a meditation guru. You simply need a scone recipe, an early start and Radio Two.

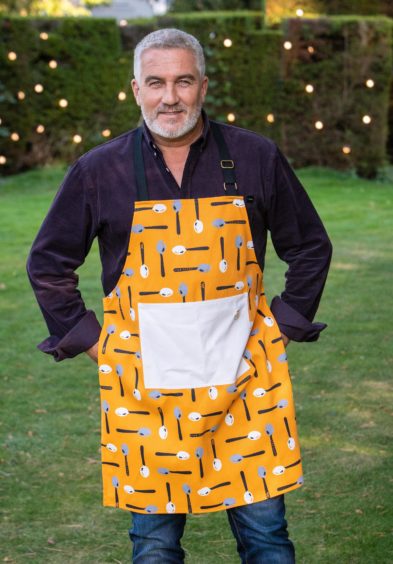

Full credit for this recipe goes to Paul Hollywood, for whom I confess a long-standing attraction (it’s the accent, the rolled up sleeves and the smoking… Paul, you can tell me I’ve burned my caramel any day) and it produces truly outstanding scones.

Preheat the oven to 220C and line two trays with baking parchment or silitmats. Put 500g strong flour, 80g softened unsalted butter and 80g caster sugar in a bowl, with 5 teaspoons baking powder. Either rub with your fingers, or use a stand mixer, to crumb the mix to sandy consistency. Add two eggs and mix gently, then slowly add 250ml whole milk until you have a soft sticky dough.

Gently knead on a well floured surface very lightly, just until the dough is smooth (don’t over-work it).

Roll to 2.5cm thick and cut out scones with a 5.5cm cutter (dip the cutter in flour between cuts to stop it sticking). Leave the cut scones to rest for a few minutes then brush the tops with egg wash. Bake for 12-15 minutes until golden and well risen.

Forget meditation, there can be no better way to start the day than a warm breakfast scone, buttered and well jammed, before anyone else has lifted their head from the pillow and you’ve firmly put the world to rights – in your own head at least.