Pioneering brain surgery has given essential tremor sufferer Ian Sharp the miracle he’s waited 30 years for.

Mr Sharp has gone from being unable to use his hand to having no tremor in it in the space of a few hours, thanks to the transformational surgery.

He is the first patient in Scotland to undergo the new ultrasound treatment, offered by Dundee University at Ninewells, which has remarkably stopped the tremor in his left hand.

Mr Sharp says: “I couldn’t do anything with my left hand before.

“It is a miracle and very emotional – I was welling up at the time and I still get emotional now.

“It’s 30 years I’ve had this and now there’s no shake.”

Mr Sharp this week reunited with Dr Tom Gilberston, Consultant Neuorologist and Honorary Senior Lecturer with the School of Medicine, who led the team that carried out the procedure.

And although Mr Sharp has experienced side effects, including numbness in his tongue and chin along with some walking issues, he remains hopeful.

“For me, the benefits outweighed the risks. I’ve spoken to a man in England who went through it and his side effects have gone. I am optimistic.”

Previously, invasive surgery was required to mitigate severe tremors.

But the new treatment utilises high-intensity focused ultrasound to disrupt the faulty electrical circuits in the brain which cause the tremors.

Dr Gilbertson says: “It’s exciting and we are very lucky to have our own system so patients in Scotland have the potential to have treatment fairly quickly.

“Many patients who have lived with this condition have normalised living with their tremor.

“They become reclusive, retire early or lose employment – it’s often a hidden disability and not something people are aware of.”

How does it work and who can have it?

Dr Gilbertson says: “This is much less invasive and great for the right patient. The technology means it looks like a walk in the park, but it’s still a serious procedure.”

During the surgery, carried out in a MRI scanner, the patient’s hair is shaved and a local anaesthetic is given before metal pins are fixed to locations on their head.

Short bursts of ultrasound, increasing in intensity, are monitored by the team.

Although there is a standardised starting point for each patient, the location of each ultrasound is modified based on clinical assessment during the procedure. Every millimetre is of utmost importance.

But perhaps most fascinating is the immediacy of results.

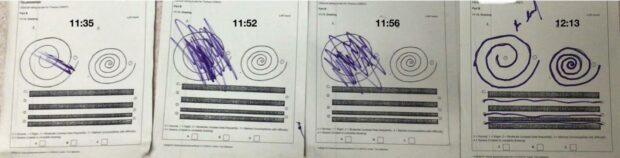

As part of the monitoring, patients are often tested on their writing between ultrasounds which by the end shows the amazing results of suppressing the tremor.

Not everyone with essential tremor will be suitable for the surgery and a rigorous process is carried out even before suitable patients are put forward for the treatment.

Dr Gilbertson adds: “It’s fantastic – neurology can be quite a depressing subject and we often have to give out diagnosis which can be very upsetting for the patient.

“Seeing real joy for the patients is exciting for me.”