At his lowest ebb, Fife-raised alcoholic Ian Doctor might have committed suicide if he’d thought there was a drink at the end of it.

But after 40-years of alcoholism, and after struggling for years to get the help he needed for his addictions, the High Valleyfield-raised 52 year-old is now determined to help others retain a life free from drink and drugs.

Sober now for 11 years, he still has to be mindful of what he calls the “f**k it button” – a tightrope of temptation he walks every day.

What is the ‘f**k it button’?

“How close is a shop? That’s how far the f**k it button is,” he says.

“I’ve always got to mind that.

“It’s constant awareness. You have to keep checking yourself, checking yourself…”

But after hitting rock bottom, Ian has found a way to stay sober and help others.

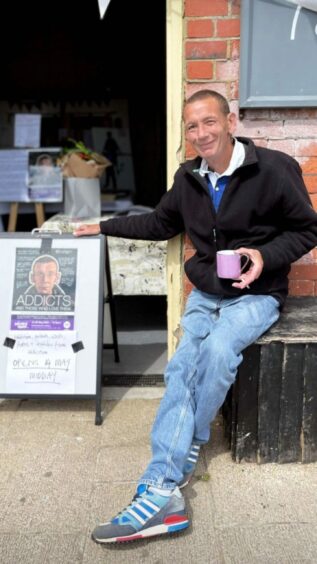

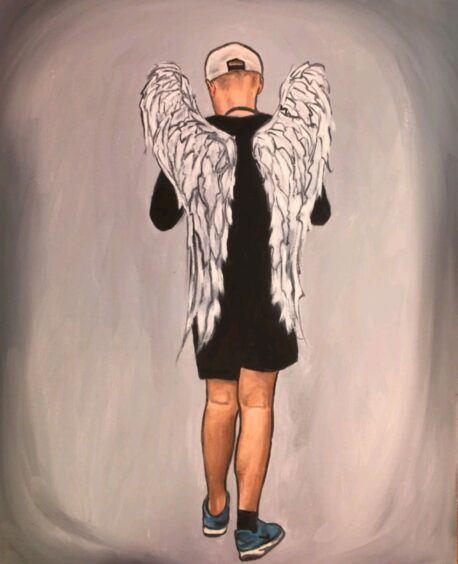

He’s a certified drug and alcohol recovery coach, who recently featured as the ‘poster man’ for an exhibition at the Edinburgh Festival.

Ian’s desire to help others stay sober

Sharing his story exclusively with The Courier, Ian, who is the nephew of Celtic FC ‘lost legend’ George Connelly – another alcoholic – says there’s a huge “nature or nurture” debate to be had in Scotland’s alcohol-saturated society.

But he wants others to learn from his experiences and realise that there are choices when it comes to relapse prevention.

People do have the power to turn their lives around, with the right support.

However, there should also be a greater understanding that behind every alcoholic, there are people traumatised by loving them – and they need support too.

Growing up in the ‘wild west of Fife’

“I grew up in High Valleyfield – the wild west of Fife!” said Ian in an interview from his home in Little Hampton, near Bognor Regis.

“I was from a mining family. Valleyfield was a mining town.

“That was one of the jokes – ‘what’s Dundee famous for? Coal and steel. What’s Valleyfied famous for? Steelin’ coal!” he laughed.

Ian described himself as “clever” at school.

However, with alcoholic parents, he says he was “never given any parental guidance”.

He was “kicked out of school” and attended Lauder College in Dunfermline where he studied engineering science.

Job opportunities were limited.

The coal mines were closing, the now closed power station at Longannet was in decline.

Having already been “in trouble with the law”, a job at Rosyth Dockyard was “out of the question”, he said.

So when he turned 16, and conscious that he was already starting to become an alcoholic within his peer group, he “shot the crow” and moved away, thinking he could leave his problems behind.

What happened when Ian moved to England?

“I put my knapsack on and left Scotland,” he said.

“I went south looking for work. I jumped on a bus and away I went.

“I ended up in Bristol then heard about lodgings in Gloucester.

“I stayed in Gloucester 10 years.”

Ian “blagged his way into an engineering workshop” and worked his way up.

He started a family young.

But by the time his first daughter was four, Ian says he was “already starting to slip”.

“I left Scotland because I was starting to become an alcoholic,” he said.

“By moving away, I thought I could leave it all behind.

“But the first thing you put in your suitcase is your problems.”

Drink was increasingly a factor in Ian’s life.

What was the impact on Ian’s family?

When his second daughter was born with a heart issue, he decided to put his “scruples” first.

He didn’t want to put his daughters through what he’d been through with his parents. So he decided to leave.

It’s a difficult decision that still fills him with emotion to this day.

“I’m still trying to build a relationship with my daughters 25 years later,” he said, his voice cracking with emotion.

“It was a pretty hard journey.

“But at least I’ve got that satisfaction now of knowing I didn’t pass it on.

“They are not addicts. They are not alcoholics. I’ve won!

“I’ve broken the f*****g chain! It hurts like f**k but I’ve broken the f*****g chain!”

How to overcome ‘guilt, shame and embarrassment’

Ian says that “after 25 years of madness”, he engaged with treatment services in 1999.

He was “finally taken seriously” in 2012 and was put in rehab for three months.

He hasn’t looked back since.

Ian says the “guilt, shame and embarrassment” faced by alcoholics – and their families – can be the hardest thing to overcome.

Addicts can put down the drink.

But the stigmas and labels often persist.

Sadly, many then decide “the only thing that softens that is more drink”, he reflects.

What has to happen, he says, is a change of mind-set.

Turning it all around

It takes courage to “make friends with yourself” and to “really change the way you think”.

There also has to be greater societal understanding.

“I turned it all around and have changed my life big style since 2012,” he said.

“I stopped being a selfish f****r!

“I came out of that rehab, and I got sucked into the services.

“Now I’m like a golden boy for Addaction – a recovery champion and all this sort of thing!”

‘Once an addict always an addict’?

While it’s 11 years since his last drink, Ian is adamant that “once an addict always an addict”.

These days he’s addicted to tea, pickled onion Monster Munch and trips to the gym.

But he’s only ever “10 seconds away” from picking up his next drink.

Amid the darkness, and the need to keep himself in check, he still manages to see the funny side.

“I can’t meditate – I’ve got a whole committee going on in my heid!” he laughs.

“They dinnae shut up for 10 seconds.

“F****n’ meditate? You’ve got nae chance, ken?”

But self-awareness for him is key and responsibility for actions also has to be taken.

“It’s like on the films,” he added.

“You’ve got a wee angel on one shoulder and a wee devil on the next having this wee argument.

“It’s like National Lampoon’s Animal House!

“That’s where it is, eh?

“I’ve got that devil on my shoulder all the time saying ‘get a drink. Any troubles? Get a drink!’.

“But rather than reflecting on the past, what I do is look to the future and start risk assessing that.”

The nature or nurture debate

Ian believes a combination of “nature, nurture and environment” can lead to alcoholism.

In the mining communities of old, there was a “work hard, play hard” culture.

But not everyone who enjoyed a drink became an alcoholic.

That’s where he believes genetics, played out in an environment like 1970s/80s Scotland, comes into force.

His parents were alcoholics, meaning he was “50% of the way there himself”.

Alcohol and Celtic legend George Connelly

Further evidence, he says, is the fact that his uncle George Connelly also became an alcoholic.

“It runs right through my f****n’ family!” he says.

Fife-born Connelly made 254 appearances for Celtic between 1968-1975.

One of Ian’s earliest memories is the legendary Jock Stein and his assistant coming round to their house when he was wee, looking for George who was “hiding p****d”.

“It’s the Scottish thing, he said.

“You can’t deny it. I know I’m stereotyping, but I’m stereotyping myself so that’s allowed, eh?” he laughed.

“Being Scottish you are just two steps from the next drink!”

Another success story, says Ian, is that he has used his recovery training to coach his uncle.

Helping with Edinburgh exhibition

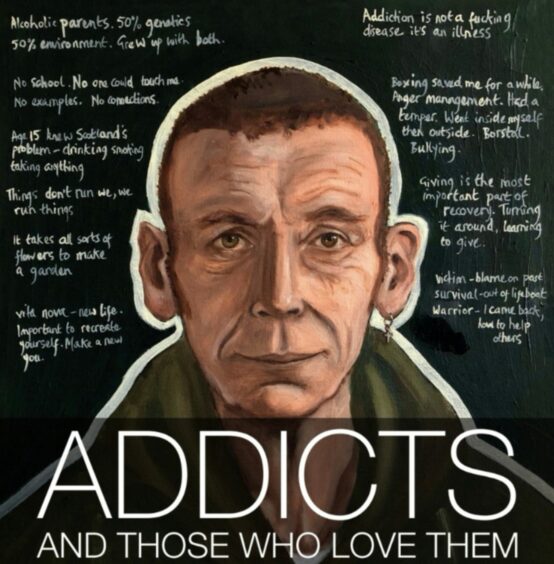

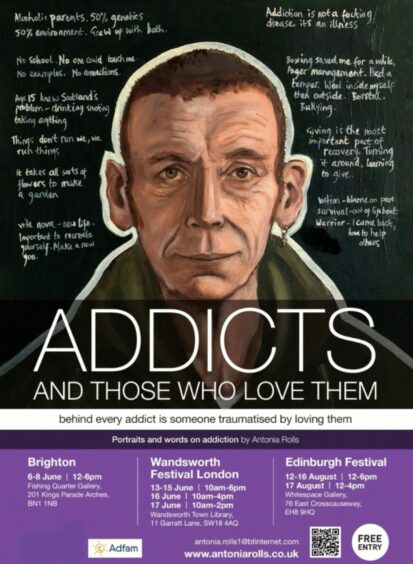

Someone else he’s helped is Bognor Regis based portrait artist Antonia Rolls who recently staged the Addicts And Those Who Love Them: behind every addict is someone traumatised by loving them exhibition at the Edinburgh Festival, as previewed by The Courier.

Ian featured on publicity material for the exhibition, which Antonia staged just months after her 29-year-old addict son Costya died from an overdose in February.

An inquest opened on August 22 and was adjourned again.

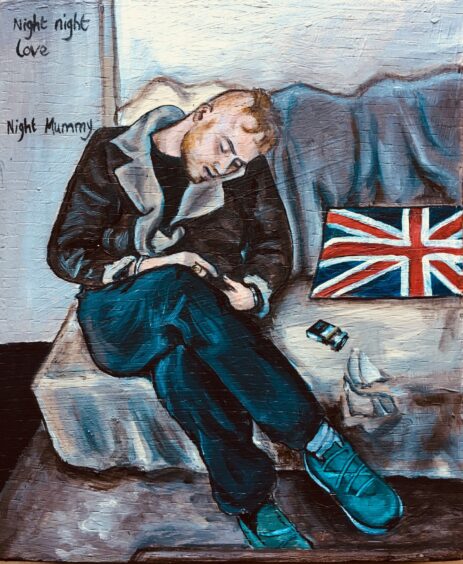

The exhibition featured portraits of addicts alongside words pulled together from interviews Antonia did with addicts to try and understand what was happening with her son.

How did artist Antonia meet Ian?

Antonia, who studied art history at Aberdeen University in the 1980s, first met Ian at her very first exhibition in 2019, Brighter the Light, which focussed on her son’s addiction.

However, when Costya “kicked off” on the opening night and it became clear that the portraits of him could never be shown publicly again, Ian was there and supported her.

They’ve been friends since.

“Ian is the first person I painted and interviewed for my exhibition,” explained Antonia.

“My son Costya was an addict and I created this exhibition to try to understand him.

“It was important to try and see what was happening in his life, and I did do so.

“He and I became very close.

“But it still did not stop his death early in 2023 from an overdose. He was 29.”

Impact of the exhibition

Antonia’s exhibition was shown in 2021 and 2022 as part of the Brighton Fringe.

However, its poignancy grew considerably since the death of her own son.

“So many of the addicts now featured came into the exhibition because they wanted to talk or wanted their faces to be seen or their stories to be told,” she added.

“More people than you might think are affected by such issues, but rarely do they have a voice.”

How to find help

*Further support is available from Scottish Families affected by alcohol and drugs sfad.org.uk/contact or from samaritans.org/?nation=scotland

DrinkLine Scotland offers a free helpline: 0800 731 4314 (weekdays 9 am – 9pm, weekends 10 am – 4 pm).

Conversation