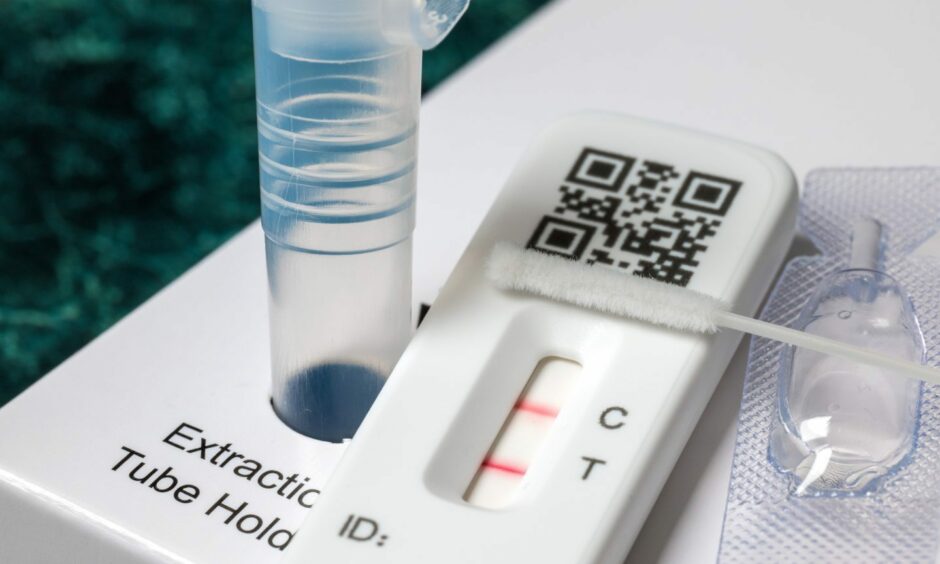

Covid-19 has been back in the news with the UK Covid inquiry accusing former prime minister Boris Johnson of “bipolar” and “completely inconsistent” decision making during the pandemic.

It comes as the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Covid-19 vaccine scientists Katalin Kariko, from Hungary, and Drew Weissman, from the United States.

For many of us, the height of the pandemic has been filed away as an extraordinary moment in history – albeit with long-term health, economic, educational and work-life impacts still unfolding.

Yet more than 3.5 years on, Covid-19 cases around the world are said to again be on the rise.

Two new variants of note – BA.2.86 (Pirola) and EG.5 (Eris) – have already shown up around the world, including in the UK and US.

Should we be concerned about Covid-19?

No one is predicting new lockdowns or anything like it as we head into the cooler months.

But with concerns again being raised about possible winter pressures on hospitals, how prepared would we be for a future global health crisis?

Are other technologies available that could add to the apparent success of vaccines?

Far UVC work of St Andrews and Dundee scientists in the spotlight

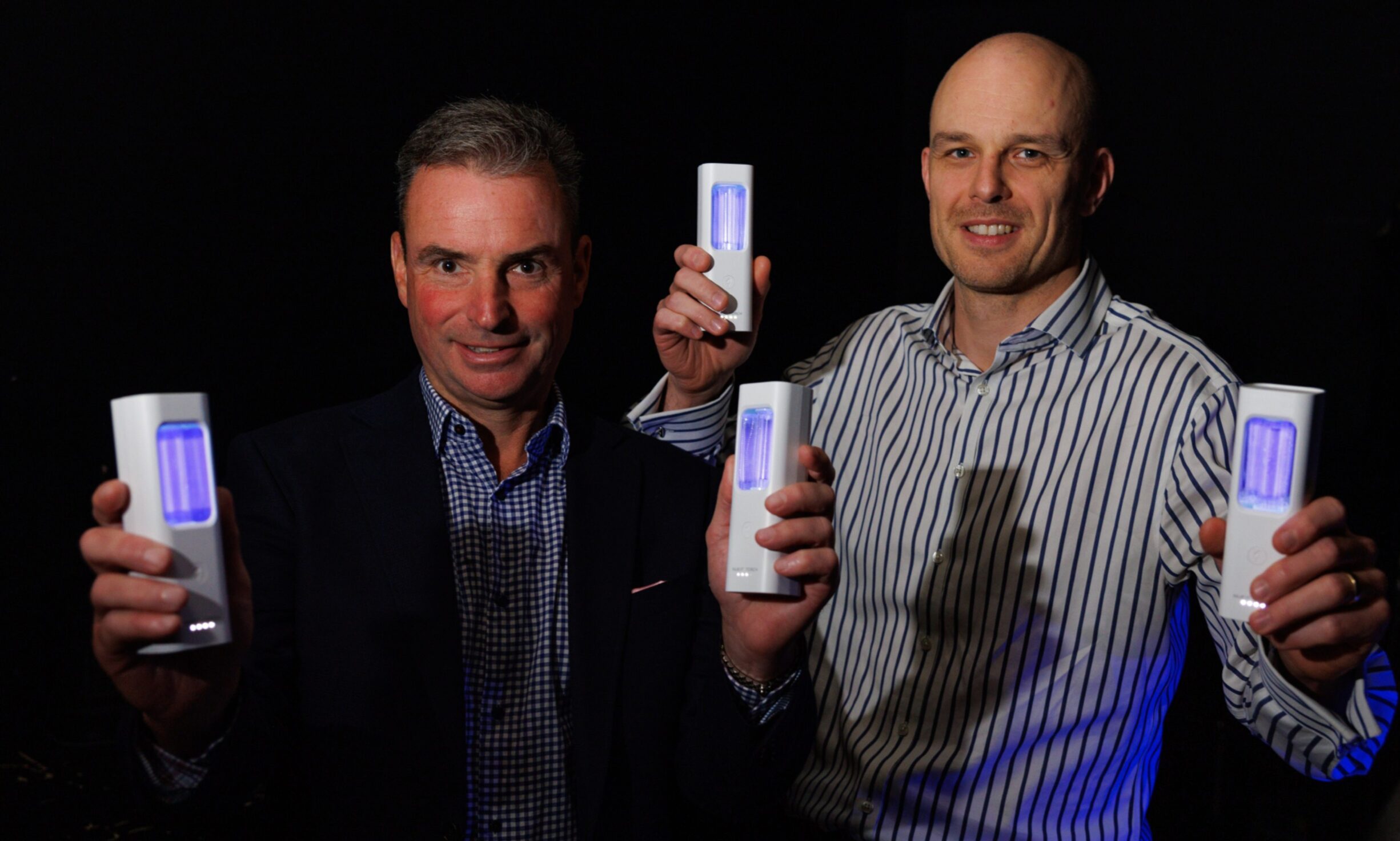

The Courier spoke to Fife and Tayside-based research scientists who are investigating whether UVC lighting is the way to a future free of Covid-19 and other disruptive airborne pathogens like flu.

St Andrews University astrophysicist Professor Kenny Wood and Dr Ewan Eadie, Head of Scientific Services in the Photobiology Unit at Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, have been studying the impact of Far-UVC lamps on human skin.

Evidence so far suggests the UVC disinfection technology kills up to 99% of pathogens in the air and on surfaces without harming people and animals present.

This, they say, could have profound implications for keeping society safe from pandemics as the technology could be used in offices, schools, hospitals, shops and public transportation.

There are three types of ultraviolet light – UVA, UVB and UVC – all of which have the potential to cause skin damage.

Using their computer model, the scientists have shown that longer UVC wavelengths can damage the skin whilst wavelengths shorter than 230nm have much more limited penetration.

UVC light from special germicidal lamps with wavelengths in the range 200nm to 280nm kills germs such as bacteria and viruses and has been used as a means of disinfecting hospital wards and operating theatres for decades.

However, the wards must be empty of people because the germicidal lamps operate mainly at a wavelength of 254nm that can penetrate the eyes and skin, causing inflammation and pain.

What difference could Far UVC technology make in tackling airborne pathogens?

Far-UVC lamps that emit at wavelengths around 222nm may be safer because proteins in the skin efficiently absorb this light and provide a natural protective barrier.

The computer codes at the heart of this work were originally developed by Professor Wood at St Andrews and have been adapted to help treat patients.

For more than 15 years, he’s been working on interdisciplinary collaboration with photo-biologists at Ninewells.

As “potentially game changing” research continues, he is very excited about the technology’s real-life potential.

“Almost all of the experimental work that we’ve done is pointing towards a low risk, very effective intervention reducing the amount of airborne pathogens that can go on to cause infection,” he said.

“The whole thing about UVC is that it doesn’t remove them – it ‘zaps’ them. It inactivates the bacteria or the viruses so that they can no longer cause infectivity.

“There has been some research which has pointed to the fact that these ultra violet lights can produce ozone – perhaps in quantities that were larger than originally thought.

“We’ve got more research we are wanting to do into just how much ozone is produced by the lights.

“But the ozone can be mitigated by a small amount of ventilation.”

What have results from inter-institutional trials shown so far?

Working with other institutions, Professor Wood said trials in the bioaerosols chamber at Leeds University had shown “spectacular” results for inactivation.

They tested it on staph infections like MRSA.

By aerosolising the bacteria in a 32 metre cubed room, they found they could sustain a more than 90% reduction in the amount of active bacteria.

Those results have been backed up recently by colleagues at Columbia University in the USA.

They deployed Far UVC lights in a room in a research laboratory at a hospital where they change lab mice cages.

They found when they turned the lights on, murine virus dropped by 99%.

What have the most recent studies involved at Ninewells Hospital?

Dr Eadie said that since they published their earliest findings a few years ago, they’ve gone on to other experiments – including a project for NHS Services Scotland – which simulated a hospital environment.

One of the most recent pieces of research involved an eye study.

“There’s the efficacy aspect: How effective are these lamps in inactivating pathogens, and then there’s the safety aspect. How safe are they in use?” he said.

“We’ve done a few studies on the safety side of things recently.

“Working with the University of St Andrews, we were looking to see if the lamps caused eye irritation.

“Obviously these lamps would be installed in the ceiling. Could people experience any irritation from being in the room?

“We had a study where we had three groups – a group where the lamps weren’t on, a group where the lamps were on at a medium level, then a group when the lamps were on a high level.

“The conclusion of that was we didn’t detect any eye irritation in any of the participants from the lamps, which was fantastic.

“We also found by sampling the environment as well we got a reduction in the pathogens that were in the environment too.

“The team has just finished a clinical trial in the Photobiology Unit at Ninewells too where we were exposing the skin to Far UVC to look and see if there’s any damage in the skin caused.

“We went to really quite high doses.

“But we couldn’t see any visual change to the skin from the lamps.

“We also couldn’t detect any significant DNA damage.”

What’s next for the Far UVC research?

Having organised a conference in New York during the summer, and with a follow-up gathering now arranged for St Andrews from June 19 to 21 in summer 2024, the research is “gathering momentum”, they say.

Dr Eadie would like to see more “real-world” information about the technology.

Worldwide, he said it’s been trialled on cruise ships and oil platforms where infectious disease spread might have a significant impact.

It’s also been trialled in food storage and production environments.

For example, strawberries with Far UVC light on them remain mould resistant for longer.

He also knows of trials in farming operations, for example, to combat avian flu.

How likely is a mass roll-out of Far UVC technology in the ‘real world’?

Dr Eadie sees Far UVC as another weapon in the arsenal of humanity – a bit like plugging holes in Swiss Cheese.

However, with debate still ongoing about how much of disease transmission is airborne, he feels the roll out of the technology on a mass scale is still a “risk-benefit” decision.

While the obvious potential causes of harm appear low risk, and while there might be consent issues if the technology was installed in public buildings, the biggest hindrance probably remains cost.

“I guess if you buy it and install it in your office block, how do you really prove it was a good investment?” he said.

“You would then have to monitor staff sickness for the next year or something.

“But if you get to the end of the year and find it hasn’t made any difference to your staff sickness, what do you do? You’ve already shelled out the money!”

Professor Wood, who’d like to understand more about the physical processes of what’s happening, drew comparisons with the take-up of vaccines.

Do you need to get to some threshold level of coverage for it to be effective?

A view from the commercial world

New York-based businessman Ashok Chaudhari, 56, who approached Danish company LED iBond to advance the technology three years ago, has Far UVC solid state material products at the R&D phase.

He met Dr Eadie at the New York conference in the summer and feels frustrated that the technology is not being rolled out faster.

“We learned from the pandemic that Covid-19 was transferred mostly by aerosol,” he said.

“The beauty is this tech inactivates 99.9% of pathogens in a space.

“This tech could ultimately keep society from collapsing.

“It could just be so helpful in so many ways.”

Conversation