Angus woman Laura Shepherd was just 15 years old when she found out she had Marfan syndrome – the same rare genetic condition which had killed her own father.

But Laura had known she was “different” since she was four, when she was a “guinea pig” for local doctors investigating the disorder.

Later, she would learn that Marfan syndrome patients often present as very tall and very thin, with long limbs, crowded teeth and extreme short-sightedness.

But as a child, she thought she was just “a freak”.

“I remember going in and out of hospital constantly, getting my arm span, fingers and feet measured,” recalls Laura, 50, who lives in Forfar with her husband and their cat Elsa.

“I wore big, thick glasses from the age of four and always had a high myopia. My feet were so narrow, I had to get these specialist shoes from a shop in Aberdeen.

“I was always fainting, or falling over, and had varicose veins while still in my teens. I got picked on a lot.

“But nobody told me I had Marfan.”

What is Marfan syndrome?

Discovered by Frenchman Antoine Marfan in 1896, Marfan syndrome is a genetic condition affecting the proteins which join to make connective tissue.

It affects around one in 5,000 people and can impact all the structures of the body, from the joints to the eye lenses, and even the heart, causing a host of painful health issues.

“Our joints are loose,” explains gran-of-two Laura. “My joints in my knees are very loose. I’ve had problems with my ankles which cause stability issues.

“Generally our eye lenses also loosen and wobble. And it affects the heart. That’s the most dangerous thing.

“In a Marfan patient, the aortic valve grows. And it has to be monitored so that it doesn’t grow to the point where it could rupture or become an aneurysm.”

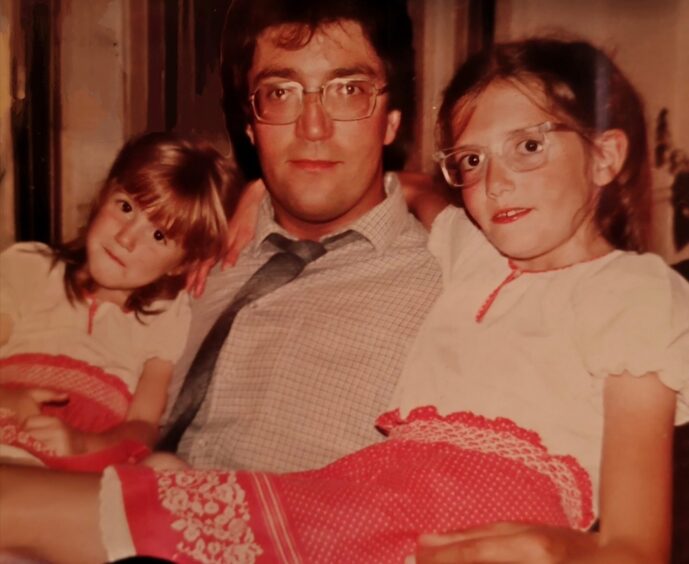

It was an aortic aneurysm caused by Marfan syndrome which killed Laura’s father when she was still at primary school.

“He was just 30,” she recalls. “He was so tall and thin, and he didn’t like being thin so he played a lot of sport and lifted weights to bulk up. And back then, you’re talking early 1980s, the doctors didn’t know much about Marfan at all, so he was never told not to.

“He was a travelling salesman and one day he was with his dad – my granddad – and he literally just got out the car, opened the boot to get something out of it, and collapsed.

“It was as quick as that.”

‘What if I don’t live to 30?’

Standing now at 5ft 11in, Laura says she was always the tallest in her class, and in her early teens she began to suspect she had the same syndrome which had taken her dad from her.

“I don’t blame my mum for not telling me, because from her point of view, dad died when I was only 10 and she didn’t want to scare me,” she explains.

“But the other side of it was that I grew up knowing I was different, but not knowing what was wrong.

“And I went through my school years with mental health issues because I knew I was different.

“So when I found out why, there was a bit of relief. But there was also the side of my head saying: ‘What if I don’t live to 30?’

“I was frightened.”

Thankfully, Laura’s regular echocardiograms (ECGs) have shows that her heart is relatively safe.

But throughout her early adulthood, Laura grappled with the limiting nature of her condition, and the self-consciousness which came along with the physical symptoms.

‘Nightmare’ of finding clothes that fit

“Getting clothes would always be a nightmare,” she says. “I’ve always been really fashion-conscious, but I hated showing my legs because I had skinny legs. So I always had to have long skirts and I could never get them long enough.

“And when it was trousers, they were always 2-3 inches too short. Online shopping has helped a lot!”

A combination of extreme fatigue, poor balance, sleep apnoea and and painful back condition dural ectasia mean that Laura has felt unable to “keep up” with people her age, even feeling shame around the effects of her illness.

“One of my best friends is 12 years older than me,” she explains. “And I used to feel very inferior compared to her, because she’s so fit and so agile.

“I almost feel embarrassed admitting it, and I hide my pain very well. I don’t want people to think I’m making up that there’s something wrong with me.”

Marfan syndrome stole Laura’s vision

But the biggest way Marfan syndrome has impacted Laura’s life has been its effect on her eyes.

“I’ve had five operations on my eyes and never ever been given the go-ahead to learn to drive, which when I was younger affected me a lot, because I used to get very frustrated,” she explains.

“I felt I’d been cheated out of something.”

After struggling with thick, heavy glasses and very limited vision throughout her teens and 20s, Laura finally got access to corrective surgery when the lens of her right eye became dislocated.

“The way I explain it is that the structure of eye is held in place by tiny elastic bands, and mine are broken,” she says. “So it causes the eye not be stable.

“You wouldn’t see it to look directly at me, it’s not like my eyeball is moving side to side, but inside, that’s what’s happening.”

Laura had an artificial lens fitted to the front of her right eye when she was 41, and for a while, that was her “miracle” solution.

“It was like a wee miracle,” she says sadly. “When I woke up and had the patch removed a day later, I was like: ‘I can see birds in the sky! I’ve never seen birds in the sky before’. So I got both eyes done.”

Unfortunately, although she continues to have vision in her left eye, Laura’s right eye has deteriorated to “just a cloud”, and she has been on a waiting list for a corneal transplant for the past three years.

“They’ve stopped doing them at the moment at Ninewells, as they’re not getting tissue donated,” she explains.

Pregnancy fears over hereditary condition

When Laura became pregnant with her son Declan, she was anxious as she knew there was a 50/50 chance she’d pass on her hereditary Marfan syndrome.

But it was her son’s experience with Marfan syndrome which ended up helping Laura come to terms with her own.

Diagnosed as a child, 6ft 4in Declan has suffered several knee dislocations, undergone four operations on his feet to straighten his hammer toes (another Marfan symptom) using metal pins, and has had an aortic valve replacement – all before his 33rd birthday.

“It was a 10-hour operation,” says Laura of the valve replacement. “When they were monitoring his heart, they said it was getting to the point where it could cause an aneurysm. It was very, very scary.”

Religious beliefs honoured with bloodless surgery

Both Laura and her son are Jehovah’s Witnesses, meaning Declan’s surgery had to be entirely bloodless, in order to fit in with their religious beliefs, which preclude them from blood transfusions.

As a result, Declan had a metal valve fitted into his heart.

Although contrary to popular belief, Laura points out that Jehovah’s Witnesses do accept other forms of life-saving treatment, such as cell salvage.

“It does mean we have to be prepared much earlier and consult with the doctors involved,” she explains. “But my son’s surgeon was more than happy to do the bloodless surgery.”

Due to his knee dislocations, Declan suffers severe pain and often has to walk with sticks. Where Laura is able to work short shifts Monday to Friday, her son is unable to work.

And in 2015, when Declan’s own son Jacob was born, the family learned right away that he too had Marfan syndrome.

However, Laura is heartened by how different the world is for eight-year-old Jacob, compared to how things were for her growing up as a child with Marfan.

Difference in Marfan syndrome awareness is ‘amazing’

“I was pretty positive when my son was born that he had Marfan syndrome, because he was long and thin with long limbs, long fingers. He had the same characteristics as me,” she says.

“But even back then they didn’t do much for him as a baby 30 years ago. It wasn’t until he got to his teens that he was going for regularly echocardiograms and being put on medication.

“Whereas with Jacob, from the day he was born, they were able to help. He started on beta blockers at six months old, he’s had heart scans every year, he’s wearing his glasses.

“They’re already talking about doing preventative surgery on his eyes when he gets older so that he doesn’t have to go through what I’ve gone through.”

For Laura, the heightened awareness of Marfan syndrome in the medical community is bittersweet. On the one hand, she’s relieved that her grandson will grow up with understanding from his doctors, parents and teachers.

On the other, she mourns the experience she – and her father – could have had if more was known earlier.

“There’s an element of feeling sad that it all wasn’t there for my son, or for me,” she reflects.

“In saying that, the difference is amazing. Now, even the student doctors know straight away that I have Marfan, just from looking at my hands.”

Glam gran Laura will have ‘diamante stick’

Although she lives a full life, regularly singing on stage, going to the gym for light exercise, crafting jewellery from second-hand shop finds and dancing at weddings, Laura wishes that she had a Marfan community of her own in Scotland outside of her family.

“There’s an amazing community of people on social media, and I have a few connections through that now,” she says.

“But in terms of the Marfan Foundation, everything’s in America. They have forums and meetings there, but they don’t have anything like that in Scotland.

“It would be fantastic if we could have something like that here.”

And despite her acceptance of her illness, Laura admits she struggles with some ideas of ageing with Marfan syndrome.

“When I do actually have to use a stick, I’m going to get a diamante one,” she laughs. “But I’m just not mentally there, I haven’t bridged that yet.

“Right now, I worry about my son and my grandson – and that keeps me from worrying about myself.”

Conversation