When Andrew Stevens worked as a bus driver in Edinburgh, it should have taken him 20 minutes to drive home to Fife at the end of his shift.

But because the Fife dad had severe OCD, the journey could take him more than an hour – as he returned to bumps in the road where he feared he had hit a pedestrian.

In reality his car had likely driven over a pothole or a speed bump.

But in his mind he couldn’t take the chance of having knocked someone over so he would go back to the spot just to check and make sure.

Andrew, 43, from Inverkeithing, would also wash his hands many times so they were completely clean and stay away from certain parts of his house if he thought they were unhygienic.

“I remember washing my hands a lot,” he says.

“I would wash them but then question if I had done it because if someone was talking to me at the time, I wouldn’t remember.

“So I would wash them twice.

“Before I knew it, I would be standing at the sink washing my hands several times.”

He continues: “After I finished work I wouldn’t go near my kids until I had had a shower – I was worried in case I had brought home any germs.

“I could be in the shower for an hour to an hour-and-a-half just to make sure I was completely clean.”

For ten years the Fife dad-of three struggled with extreme OCD.

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition where a person has obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours.

But after getting support from the RAF Benevolent Fund, he has been able to better manage his condition.

Andrew hopes his story will help to raise awareness of OCD making it easier for people to get help.

What triggered Andrew’s OCD?

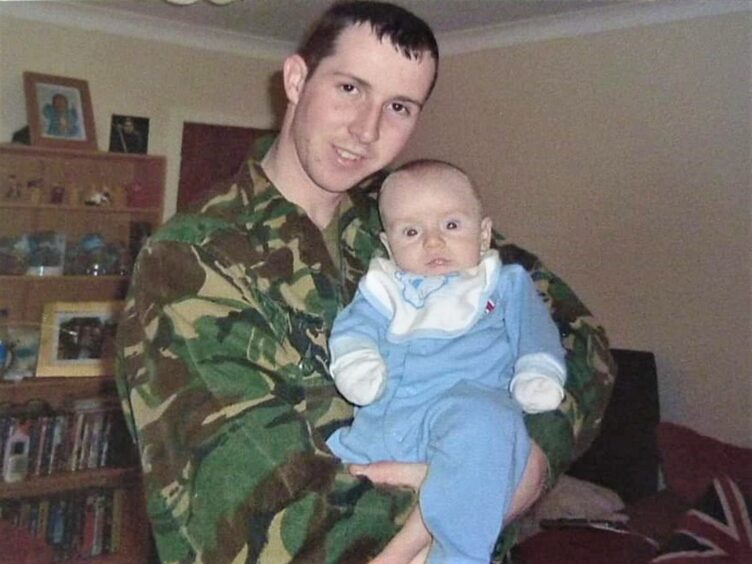

Andrew joined the RAF at the age of 18 and served for seven years as a painter and finisher working on Tornados based out of RAF Lossiemouth.

But his military career was cut short when he was made redundant in 2007.

He managed to secure a job with Lothian Buses, but taking three days off from work due to illness triggered his OCD, he says.

“If I was feeling unwell in the RAF I would go to the medical centre on the base and see the doctor,” he explains.

“You would then be signed off for a day or two or a week, depending on what it was. It was regulated like that.

“But when I started working as a driver for Lothian Buses in Edinburgh I wasn’t sure what to do.

“One day I wasn’t feeling well so I called in to say I had a really bad cold and that I thought it would be too dangerous for me to work.

“They asked if I was ‘calling off’ so I asked what that was. They explained that I would need to self-certify.

“I stayed off for three days and called them every day to let them know I wouldn’t be in.”

But when he went back to work it was explained to him that if he took any more time off, he could face disciplinary action.

“I was then worried about losing my job so I started to obsess about my health.

“I went out of my way to avoid catching any bugs and becoming ill.

“That is when it all started.”

Signs of OCD

The Fife dad’s battle with OCD first manifested with excessive hand-washing and long showers.

But soon Andrew started to worry about the foods he was eating.

“I didn’t want to eat fresh fruit because it could have been coughed on before I bought it,” he remembers.

“Or if there was a chocolate bar which looked slightly bashed, I wouldn’t touch it.

“I couldn’t watch my wife Claire making dinner because I would find something wrong with it and not eat it.

“And sometimes if I had made my own dinner and thought there was something wrong with it, I would put it straight in the bin.”

‘Obsessing about everything that could go wrong’

Andrew would also re-make his bed every night before sleeping in it and pace around the house checking to make sure he had locked everything and that it was secure.

“I started obsessing about everything that could go wrong.

“I would come home, do my routines – my hand-washing, my showers, my food – and I wasn’t really communicating with anyone.

“It was exhausting.”

Andrew said his wife Claire tried to encourage him to seek help, but he admits he was stubborn and refused to go to the doctor.

Andrew’s OCD diagnosis

Over the years, Andrew’s mental health began to deteriorate further.

He would end up taking half an hour to walk 200 metres to his car after work because he would see something lying on the pavement.

He would spend time looking at it, wondering if he could catch something from it.

“Eventually I would take a picture of it on my phone so I could walk away.

“That photo would re-assure me that I had thoroughly checked it.”

In December 2016, Claire could see how exhausted her husband was and she intervened.

“She pretty much ordered me to go to the doctor. She made me promise I would tell him everything.

“So I went to the doctor and I told him all about my routines and he asked me a few questions.

“He then diagnosed me with severe OCD.”

Support from the RAF Benevolent Fund

Andrew was prescribed with medication used to treat OCD and was signed off work.

He ended up staying in bed all day and wouldn’t leave the house. At one point he even considered taking his own life.

But instead Andrew reached out to the RAF Benevolent Fund – a charity that provides welfare support to former and serving air force personnel and their dependants.

It enrolled him in a counselling service and slowly the darkness started to lift.

“I had counselling once a week for around six months and this really helped.

“What really sticks with me is the speed in which the Fund stepped in and offered support.

“It saved my life.”

Living with OCD

As well as the help from the Fund, Andrew also credits his family – sons Craig, 19, Lewis, 17 and Andrew, 12 – for their support – particularly his wife.

“I wouldn’t be where I am without Claire’s help, she was loyal and very patient.”

Today Andrew is still living with OCD, but he has found a way to manage it by making lifestyle changes.

As well as doing a less stressful job working part-time at the Tesco Mobile phone shop in Dunfermline, he also does voluntary work.

“I volunteer with the Air Cadets, training them as part of the fieldcraft team and I love it. That is my passion.

“The other big thing which has changed in my life is that I go out walking a lot with my dog, Shadow,” he continues.

“I have had him for two and a half years now and it’s great because he forces me to go out. He is my best mate and we are now out all the time.”

“The OCD is always going to be there.

“But the difference now is how I manage it to make sure it doesn’t spiral.”

Conversation