Sitting on the top deck of a double decker bus as they made their way home from school, Harry and his best friend were chatting and giggling in the way that 12-year-old boys often do when suddenly, the atmosphere shifted.

A group of older youths, not from their school, started shouting at them.

“Why are you sitting next to a ‘P***?’ the older youths demanded of Harry, referencing that his best friend was of Pakistani-British origin.

The two boys continued giggling, not quite sure how to react. Then one of the white youths got up and walked down the aisle of the public bus to where the pair were sitting.

Without warning, he kicked Harry in the head and slammed his head against the window – leaving him bloodied, bruised and in shock – before the youths stopped the bus and ran off.

Alerted to what had just happened, the bus driver came upstairs to check on the boys and, discovering that Harry’s head was bleeding significantly, drove his bus off route to the local hospital where Harry received treatment.

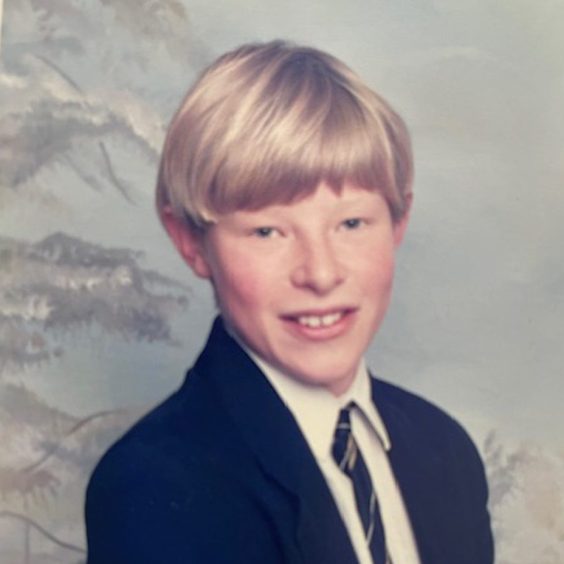

Twelve-year-old Harry and his mum had no Victim Support to turn to after the attack

It’s more than 20-years since this unprovoked attack rocked the life of Harry and his family.

But more than two decades on, this incident involving her son still inspires Perth woman Elizabeth (Elizabeth has asked that we withhold her surname to protect her full identity) to volunteer with Victim Support Scotland.

For eight years, since retiring, she has helped deliver free and tailored support to victims and witnesses of crime.

For the past four years this has been in the Perth and Perthshire area.

Now the retired public sector worker is backing a new national recruitment drive by Victim Support Scotland seeking more than 200 volunteers across the country.

In an interview with The Courier, Elizabeth explained how she first started to volunteer – when retirement gave her time – after discovering that following her son’s attack, neither she nor her son felt they had anybody to turn to during the investigation.

“What was really noticeable after the attack was there was no real follow-up or support for him or us – it was all quite a shock!”, she said of the incident which took place in 2002.

“I expect it’s one of these things that lots of families experience. Objectively I guess it’s quite a low level incident. But for the family it was quite frightening.

“My son was very young and out of the blue, he was attacked.

“These bullies saw a white boy and a Pakistani boy and decided they were going to have a go. They were small and vulnerable.

“He was taken completely by surprise and the shock lasted a long time.”

What impact did the attack have on 12-year-old Harry and his mum?

Elizabeth, who’s originally from Manchester and has lived in Sheffield and Bradford, admires the resilience of children. Her son, now 34, went on to live and work abroad.

However, for a long time, Harry struggled to go back on a bus.

At first, he was nervous about going by himself. When he did go back, he would sit down the stairs.

But he also rarely talked about the attack.

When he did, he’d say the sort of things that Elizabeth now hears all the time from victims of crime. He’d say things like ‘why me? and ‘what did I do wrong?’ – questioning his own behaviour rather than those who had perpetrated the action.

Reflecting on the incident, which took place in Sheffield where they lived at the time, Elizabeth says it’s “interesting” that the Pakistani boy was not attacked in what was clearly a racially motivated attack by cowardly bullies.

Living in a “mixed community”, the Pakistani boy was “just his mate”. Race was never an issue for them or their peer group.

However, what would have benefitted Harry greatly, says Elizabeth, would have been the opportunity to talk to someone independent of the family – a service that wasn’t available in those days.

Why would Victim Support have helped Elizabeth and her son after the attack?

“Kids don’t often want to talk about things to their mum and dad,” she said.

“Sometimes they get on a lot better speaking to someone with no axe to grind, totally independent, who can listen sympathetically if they are worried, questioning – why did it happen to me? I’m feeling scared? Am I being silly to feel scared?”

Elizabeth says that what she’s learned from working with Victim Support Scotland is these are common questions people ask irrespective of the crime.

It’s the impact of the crime on the individual that’s the “unifying and common factor”.

“It doesn’t really matter if it’s somebody who’s had their purse nicked from a bag in the supermarket or a burglary,” she said.

“It doesn’t really matter if it’s somebody who’s been stalked or someone who’s been subject to years of domestic or sexual abuse in the family, or somebody who’s been randomly attacked like Harry was on the bus.

“It’s not the nature of the crime that determine how people behave. It’s the impact.

“Everybody says exactly the same thing: Why me? What have I done? Did I provoke this? I’m so frightened. All these mood changes. Is it me? Am I going mad?

“And also thinking that because of the feelings that they’ve got – they cry for no reason, they get angry, they have mood changes, they can’t sleep, they can’t eat, they are suspicious, they are frightened.

“What we say is you are not going mad, it’s horrible but absolutely normal what you are feeling.

“Because the impact of crime, no matter what the crime, is the same for everybody. It’s quite astonishing when you hear people talk about it – how similar everyone’s feelings are.”

What is it like being a Victim Support Scotland volunteer?

Elizabeth first volunteered with Victim Support in England around eight years ago when she retired. However, for the last four years she has been doing so for Victim Support Scotland in and around Perth.

When she joined, she had three full days of training going through impact of crime on individuals and looking at case studies. They had talks and instruction about how they support people in court.

She does a lot of support on the phone. She learned how sheriff courts work.

Crucially, she said, Victim Support Scotland were very clear about defining volunteers’ roles.

Rather than being counsellors or therapists, it’s made clear they are a friendly but trained listening person who’s going to listen in total confidence and signpost to other organisations that might provide practical assistance where appropriate.

A paid area co-ordinator will send volunteers like Elizabeth a referred list of names/telephone numbers and a brief note of what has happened to that individual.

Her main job is to then phone people, introduce herself, explain what they can offer, then it’s over to the individual if they want to talk.

“The emphasis is on confidentiality,” she added. “It’s amazing how much they’ll talk to a complete stranger. It’s very much their decision. There’s no compulsion to talk to us.

We are not investigating things. There’s a lot of listening to what people are saying.

“But of all the people I’ve done over the years, very few have said no. Some will want to talk for one or two sessions.

“It can be for 10 minutes or 40 minutes, as long as they want. Sometimes it’s just talking it through, talking it out, and giving assurance that what they are feeling is horrible but normal.

“They’ll say ‘I’ve got your number, if I want to talk again I’ll give you a ring’. It’s very much their decision.”

What range of crime victims has Elizabeth spoken to over eight years?

Elizabeth has spoken to everyone from victims of domestic abuse and burglary to coercive control, sexual abuse and scam victims. The devastating commonality is “violation” and an “absolute loss of trust” that saps peoples’ confidence.

It comes as The Courier has been reporting how victims of crime must be the priority in any form of justice, but during parole hearings they feel silenced and ignored.

While Elizabeth has had first hand experience of a crime being committed against her family, that’s entirely co-incidental and she would encourage anyone with time on their hands to consider giving volunteering a go.

“It’s really worthwhile,” she said. “It’s not demanding in the sense of time. I can arrange the telephone calls around my week. You have a degree of control over that.

“The training for volunteers is very solid. You feel you have a solid base. You don’t feel you are floundering. The support is also ongoing. The area coordinators are there to talk too if you feel things are getting difficult. They are very supportive of volunteers.

“There’s a good grounding in training and they are very clear about the role.

“Solving problems is not part of the job. You are there to listen and there are other organisations able to solve emotional and psychological problems. You can signpost people on.

“Crucially, you also feel you’ve done something useful yourself!”

To find out more about volunteering with Victim Support Scotland, go to victimsupport.scot/volunteertoday/