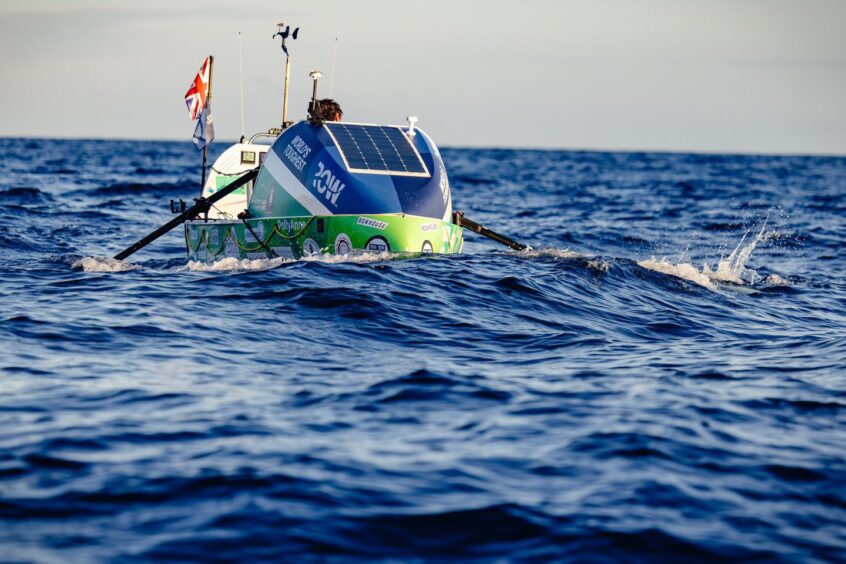

There’s a photograph of St Andrews businessman Henry Cheape that sums up his elation at officially completing the World’s Toughest Row across the Atlantic.

After his epic 3000-mile solo adventure, the 43-year old farmer and Balgove Larder farm shop owner triumphantly holds aloft two flares as he arrives in Antigua at sunset.

The photo was taken some 49 days, 12 hours and 11 minutes after he left La Gomera in the Canary Islands.

But in an exclusive sit-down interview with The Courier – ahead of a sell-out public talk he’s giving at the Byre Theatre in St Andrews on June 26 – the father-of-three reveals his belief that his family deserve as much credit, if not more, than he does.

That’s because the toughest part for him was leaving them behind in Scotland – and he will be “forever grateful” for the support they gave him.

“It’s very easy to look at me with the flares and say ‘well done Henry you did all of it’,” he says.

“But if there were five units of recognition, I could have one, my wife could have one, and the children could have one each. I have a sense of pride in all of us as a family.

“Because one of the really big things I’ve learned from what I’ve done is how much it effects those left behind at home. It had a serious impact and I’m not proud of that.

“I’m very proud of my wife and children and the way they supported me. I will forever be grateful for that, because it was bigger for them in many ways than it was for me.”

What techniques did Henry Cheape use to overcome tough times on rowing challenge?

During his seven weeks at sea, Henry experienced “some good times, dark times and amazing times”.

He faced waves the size of houses and the frequent possibility of capsizing. Stand out experiences included amazing sunrises and sunsets, an encounter with a whale that “looked after” him, an unexplained reassuring spiritual “presence” amid the solitude – and “shame”, on behalf of the human race, at the amount of plastic floating in the ocean.

When the going got tough physically and psychologically, the techniques he used to get him through were “it will pass” and “if you are feeling rubbish you can wallow in self-pity or you can get off your a*se” and row”.

But having “scratched the itch” that led him to take on the adventure in the first place, he’s also reassured himself that “old Henry and new Henry are the same” – and that it was “ok to check”.

While adamant he’ll never row the Atlantic again, his advice to anyone thinking about taking on a challenge –whether that’s “climbing a Munro or walking to Cupar”– is to “have belief and faith in yourself” and to “just do it”.

What inspired Henry Cheape to sign up for the World’s Toughest Row?

Reflecting on what inspired him to sign up in the first place, Henry insists there “wasn’t a lightbulb moment”. He didn’t have a lifelong ambition to row the Atlantic. But what he did have was a lifelong ambition to have an adventure.

No stranger to “messing about with boats” on family holidays in the west of Scotland, when he came across an advert for the World’s Toughest Row, he felt “this was the way to scratch the itch”.

Securing his second hand R25 Polly Anne rowing boat, which won her class for the 2022 race, and passing rigorous safety checks by the organisers, he became the quickest person to sign up and compete.

But in hindsight, this “condensed campaign” was a good thing as it reduced the impact on his family.

Did Henry Cheape have a daily routine?

When Henry set off from the Canary Islands on December 13 – knowing that he’d be away over Christmas – he’d already been “ascending the physical and psychological challenge” of what lay ahead.

He wanted to complete the row in between 40 and 50 days, taking enough food for 85 days as a “worst case” scenario. Carrying a message of sustainability, he took as much locally-produced dehydrated produce as possible, consuming 7000 calories per day.

Keeping his clock at GMT – the same time as at home – Henry knew routine was important. Both of his late grandfathers were prisoners of war during the Second World War. While they didn’t talk much about it until later in life, one theme that emerged was the importance of “routine in adversity”.

His days on the boat began at 4.30am

“Broadly speaking, my first get up alarm was about 4.30am each day and that was to check progress, check the boat, check to see if the drift was acceptable to achieve a run rate to my target for that day,” he explains.

“I’d have another hour’s sleep, then at 5.30am do the same again. I’d probably be up by 6 or 6.30am – row for 90 minutes until 8am, phone home at 8am for a two-minute satellite phone conversation with my wife and children before they went to school.”

He says he would then have breakfast: “Have a shave, do what we all do in the mornings. Then row until lunchtime – a solid four-hour block.

“I’d stop for 20 minutes, have something to eat, row a solid four hours until 4 or 5 in the afternoon, have a quick break then row until 8pm.

“Unless there was a very good reason, that was it. Stop, give myself an hour off, read a book, do some fishing. listen to some music, relax, give my body some time, phone home between 8 and 9, phone my weather reader Angus Collins, then go to bed sometime between 9 and 10.

“There were occasions where I had to row all night or couldn’t row during the day. But of the 49 days, that was probably what happened on 35-40 of them.”

Weather ranged from ‘mind bogglingly calm’ to being ‘spat out’ by raging seas

Despite all his planning, Henry says the scale of the weather was “bigger than you can possibly prepare for”.

This ranged from the silence of “mind bogglingly calm days” 1000 miles offshore, to the other “alarming” extreme when he had to hunker down in his watertight cabin as waves crashed over in 30 knot winds and his boat was repeatedly “spat out” in foaming seas.

He didn’t experience a 360 degree capsize in his self-righting vessel, but he did tip to 90 degrees twice.

Thinking about home “every minute of every day”, Henry said the tools he used in his “psychological tool box” worked extraordinarily well.

But he admits he physically and emotionally “crashed” 40 miles from the end. He puts this down to being so excited about seeing his family that he stopped drinking, eating and sleeping properly.

Losing two stone over seven weeks – yet becoming fitter than he’d ever been – his body also “crashed” around 36 hours after arriving in Antigua, and it took him several months to recover.

Before departing, Henry had an unspoken objective to beat a crew in every class. He is proud that he achieved this – finishing 26th out of 38 entrants over all.

He’ll also never forget the first hug from his wife, who was waiting for him amongst the fanfare at Antigua.

While he’d been fantasising for a week about a cold fizzy citrusy drink with steak, he laughs about the “average burger with chips and warm beer” that was actually his first “proper” meal in seven weeks when his wobbly sea-legs stepped ashore.

What’s it like for Henry Cheape to be back home in St Andrews?

Now back home at Strathtyrum Estate and the Balgove Larder, Henry reflects that, overall, he felt like a “pretty inconsequential guest” when whales, dolphins and tuna whizzed past without the need of a boat or lifejacket.

“There was one occasion when a whale came alongside the boat and it didn’t feel remotely scary – it felt like the opposite,” he says.

“It felt like it was coming along to say ‘I’m keeping an eye on you’, like a great big arm around me like a big hug. That was extraordinary.”

Having taken his late grandfather’s Bible with him – which he admits he didn’t open once – the “spiritual or faith side” he experienced wasn’t necessarily connected to nature.

Why did Henry feel ‘ashamed’ in the middle of the ocean?

A man of “faith” – although not a churchgoer – at one point he says he felt an overwhelming “presence” while alone on the ocean which he hasn’t felt before, or since.

But there’s no doubt the thing he feels most “ashamed” of is the amount of predominately plastic rubbish that’s out there.

“I felt really ashamed on behalf of us all that this exists, because of us as a species dumping it in the environment,” he says.

“To say that plastic is ok because we recycle it isn’t ok unless we recycle it. I caught bits of plastic when I was fishing 1000 miles offshore.

“The commercial fishing detritus out there too. One of the other crews reported seeing 5km of rope on the surface, 1000 miles from shore. You don’t need to row across the Atlantic to know that’s not ok.”

Henry will appear at An Evening With Henry Cheape: The Fastest Scot to Row the Atlantic Solo in the Byre Theatre, St Andrews, at 7.30pm on June 26. The event is sold out. Journalist Magnus Linklater will interview Henry on stage.

Conversation