Bridget Bradley’s first memory of having an uncontrollable urge to pull out her own hair was when she was around nine years old.

The 35-year-old, who is a lecturer in Social Anthropology at St Andrews University, says there was no big life event or trauma which might have caused her to develop the hair-pulling disorder – known as trichotillomania.

But she says that once it began, she found it very difficult to stop.

“There was nothing in my life causing me huge amounts of stress more than the typical child experiences,” she explains.

“I have no idea where the urge came from.

“But once it started, it became impossible for me to stop.

“It started with my eyebrows. I just began pulling out every single hair with my fingers.

“I got satisfaction from doing it, but I also had deep shame and guilt.

“Like why am I doing this to myself and why can’t I stop?”

The mum-of-two, who lives in Balmullo, is one of around 350,000 people in the UK thought to be affected by trichotillomania.

It’s estimated four million people in the UK and Ireland who struggle with body-focused repetitive behaviours (BFRBs).

These include: skin-picking, nail-biting and hair-pulling.

After struggling with the disorder for over ten years, Bridget started studying the condition before going on to do a PhD on it.

She then became instrumental in setting up a charity supporting people living with Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviours (BFRBs) in the UK and Ireland.

What is Trichotillomania?

According to the NHS, trichotillomania, also known as trich or TTM, is when someone cannot resist the urge to pull out their hair.

They may pull out the hair on their head or in other places, such as their eyebrows or eyelashes.

Trichotillomania usually starts between the ages of 10 and 13 years old.

It’s not entirely clear what causes it, but it could be: a chemical imbalance in the brain, changes in hormone levels during puberty, genetic or a person’s way of dealing with anxiety and stress.

Why were Bridget’s high school years the hardest?

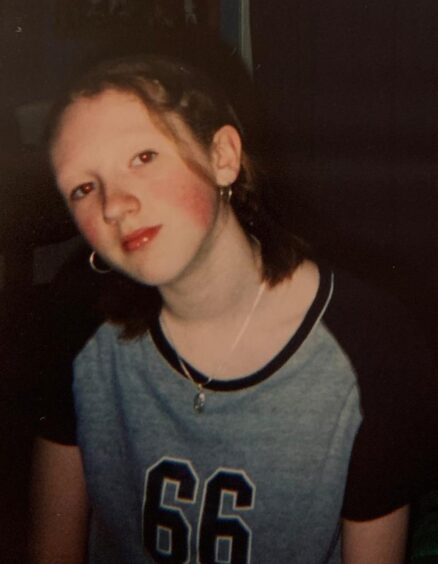

When Bridget, who grew up in Edinburgh, left primary school she started pulling her hair out from the middle of her head.

“My older sister helped me to style my hair differently to hide the thinning middle parting,” she says.

“I learned to develop strategies to conceal it because the shame was so profound.

“My mum and dad didn’t know how bad it was because I became a master of disguise.

“Sometimes they could see me doing it and in those moments they would tell me to stop.

“But that reaction made me want to do it more.

“My high school years were probably the hardest when I started pulling more hair, more often.

“I thought I was the only one in the world who had this problem – that I was a freak.

“I didn’t know it was a condition.

“I had bald spots, the size of the palm of my hand, on both sides of my head behind my ears.

“The visible hair loss was awful.

“But even though it caused me a lot of distress, it wasn’t enough to stop me from doing it.”

Opening up about her hair-pulling disorder

When Bridget was 18 years old she started dating boyfriend Matt Roe, who she later went on to marry.

And he was the first person she really confided in.

“One night I opened up to him but I couldn’t get the words out I was crying so much.

“When I did finally manage to tell him he told me I didn’t need to feel ashamed.

“Matt went looking for information about the condition and found out it was called trichotillomania.

“Until that point I had ten years of feeling so alone with it.

“But then I found out other people had suffered from it too and that changed everything.”

What was the reaction from her GP?

Bridget made an appointment to go and see her GP, but says it wasn’t a positive experience.

“When the doctor looked at my hair loss she instantly said ‘oh it doesn’t look like it’s that bad’.

“She then said: ‘you should be grateful you are not addicted to drugs’.

“And she advised me to ‘try sitting on my hands’ – as if it was that easy.

“After that I felt so disheartened that I didn’t go looking for any more help.”

Studying for a master’s degree proved to be a turning point

In her 20s, Bridget completed a degree in anthropology at Manchester University and went on to study a master’s in medical anthropology at Edinburgh University.

And for her dissertation she decided to write about trichotillomania.

“That research project proved to be life changing because I got to meet others with trichotillomania – that led to my PhD.”

Then In 2014, Bridget started her PhD which took her five years to complete.

It included a lot of fieldwork, carrying out interviews with people affected in the UK and the United States.

“I realised how little research there was on the condition.

“And I started looking at the family of disorders known as body-focused repetitive behaviours. These included hair pulling, skin picking, nail biting.

“They are all so similar that it made sense to look at them altogether.”

Setting up the BFRB charity

In 2015, Bridget started running in-person support groups in Edinburgh and London for people with body-focused repetitive behaviours with friend, Pavitt Thatcher.

“Pavitt and I then ended up co-founding a charity – which I now chair – to help those with body-focused repetitive behaviours.

“And in 2022 we officially gave the charity a name – BFRB UK and Ireland.”

The Fife mum is also able to speak about her experience through her job as lecturer in social anthropology at St Andrews University.

She teaches and does research about health, illness and disability.

Family support helped Bridget Cope

Bridget has also credited her family for their support, particularly her husband Matt.

“I couldn’t have done any of this without him fully supporting my career.

“He has taken on the main caring responsibility for our two children Elwood, 7 and Forest, 3.

“Giving me the time and space to do all my academic things.

“While he can struggle to understand it, he also gives me the space to work through my hair pulling.

“And it means a lot to have someone who loves you no matter what.”

‘Hair pulling is now much better’

Today the Fife mum says while she still does pull her hair, she doesn’t do it as much as she used to.

“While I was studying for my Masters my hair pulling got much better.

“And now if I lift up my head you can’t see any bald patches.

“I admit that I still do it a little bit everyday.

“But it was nothing compared to how bad it was before.

“I think it’s because I overcame something when I started talking to other people about it – the shame was lifted.

“It doesn’t have to be a horrible secret anymore.

“It wasn’t a conscious decision to stop pulling or pull less. It just happened because I was happier and felt more comfortable in myself.”

She adds: “The research and work I have done on body-focused repetitive behaviours, particularly hair-pulling, has completely changed my life.

“It’s probably the most important, valuable thing I will ever do.”

Conversation