Professor David Gray’s earliest memory is the sound of his brother trying to breathe.

“My older brother Iain was a childhood asthmatic, he had very bad asthma,” recalls David, squinting as the winter sun streams into his office at Dundee University’s Life Sciences building.

“We shared a bedroom for years and my earliest recollections are of the ambulance coming around 5am to take him away to the sick kids (Royal Hospital for Children) in Glasgow,” he says.

“I can still hear him making that typical asthmatic noise as he was struggling for breath.”

Growing up in a house full of his dad’s books, with “nothing off limits” to read, David remembers coming across a Pan Books paperback about medicine making when he was around 10 years old.

“It was by a guy called Ritchie Calder,” David smiles. “It was called The Lifesavers. And it stuck with me.

“I wanted to be involved in making a lifesaver.”

From the age of 11, David doggedly pursued his dream, crafting his secondary school choices around his desire to study pharmacology – which he did, at Glasgow University.

However, shortly after completing his PhD at University College London, David became frustrated with the research positions.

“I found that primary research wasn’t applied enough, it wasn’t immediate,” he explains. “I couldn’t see how it would make an impact quickly enough.”

How did David’s dream come true?

Keen to do what he’d set out to – “get medicines into patients” – David took a job with drug company Wellcome in 1995.

He stayed through the merger to Glaxo Wellcome and eventually to GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

And it was during this time that David got to achieve a lifelong dream – helping to make an asthma drug.

“I was involved in a project that produced a medicine which is on the market and is actually used to treat asthma, as well as allergic rhinitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

“One of the names it’s known by is Avamys. The product for COPD is Trelegy. The molecule itself is called fluticasone furoate – a nice word!”

And although his brother Iain has never taken the medicine, David’s son Euan has had it prescribed to him from a young age.

“It was one of those things where he comes back from the doctor having been prescribed this, and I look at it and think ‘I had a hand in making this’.

“So that’s a great feeling.”

‘Exciting’ developments at Dundee unit

David explains that to have a drug on the market, never mind one that’s used by your very own family, is a rare triumph in an industry with so much trial and error.

“I’ve worked probably 30-odd years now and that’s the one product I have on the market,” he says, to put things in perspective.

“Drug discovery is conceptually very simple – you just need a molecule that has all the right properties to do what you want it to do and none of the bad properties.

“But we have a high failure rate because it’s difficult to find that molecule.”

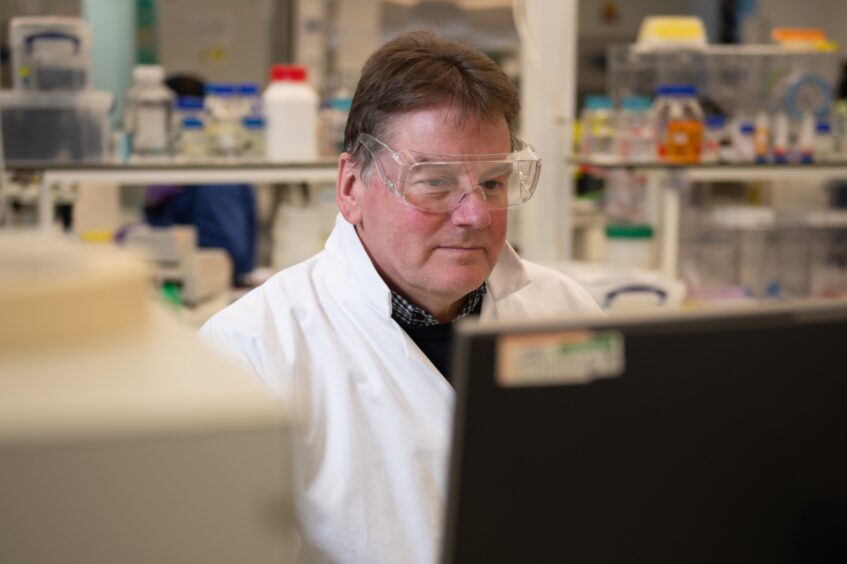

However in 2010, David joined Dundee University’s Drug Discovery Unit as their head of biology.

There he’s been part of a team working on different diseases, primarily tropical and parasitic diseases.

And he’s excited to have two molecules in “phase 2 clinical trials” currently.

“That’s where they see patients and you find out if they work for the first time,” he smiles. “So that’s exciting.”

Potential cancer drug from Dundee work?

One drug, he explains, an antimalarial, has “data coming back that says it does what we hoped it would do”, which is promising.

The second drug started off as something to treat a life-threatening parasite-borne disease known as sleeping sickness.

But unbelievably, when David’s team looked at the data, they found that the same target might work in the treatment of cancer.

“We did some work to show that it would work, and then partnered it with a company in Canada who have taken it through clinical trials,” explains David.

“We’ve seen results in phase one trials (which involved patients for whom all other treatments have failed) which suggest it works.”

And he says the American regulatory body FDA have deemed the drug “sufficiently exciting” to fast track it into phase two.

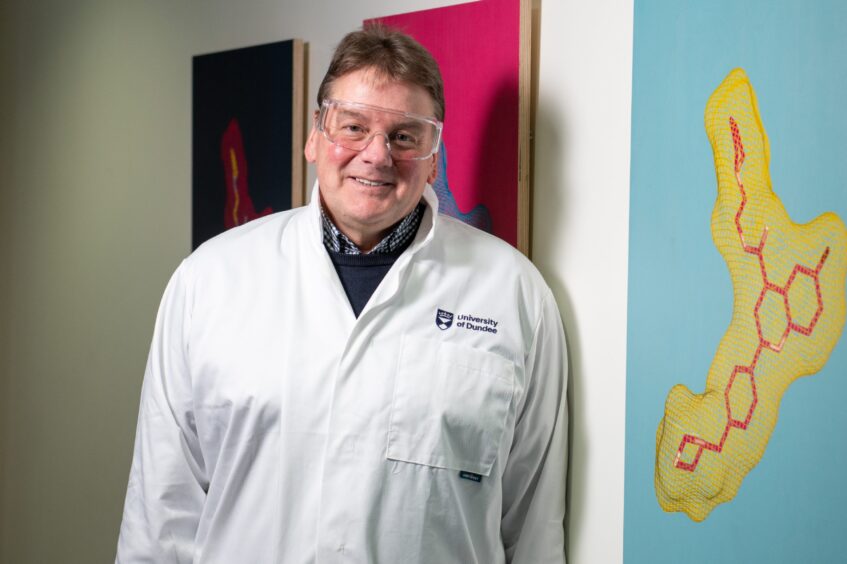

“This is an idea, a discovery and chemical matter which have all come out of Dundee, out of this building,” David says proudly.

What makes Dundee researchers so special?

In theory, this could mean his tally of drugs on the market could jump from one to three before the end of his career is even in sight.

But to David and his team, it’s not about individual glory, or even shared kudos.

It’s about getting life-saving medicines to the people who need them, and he’s proud to be part of the Dundee centre doing just that.

“In the DDU, we’re looking at the neglected tropical diseases and delivering medicines no one else will work on because there’s no commercial market.

“We have to produce medicines that are effective but also cheap.

“If we don’t do it, nobody else will.”

David Gray: Dundee ‘deserves’ improvements

Although he hails from the west coast, David has history with Dundee and his adopted home of Fife, where he lives with his wife, their sons and Staffordshire terrier Cassie.

“My dad was evacuated from Clydebank to Cupar during the Second World War, and he went to Bell Baxter, which is where both of my boys have gone now too, ” he reveals.

“We used to come through on holiday to Fife and Dundee occasionally. It was quite a depressing place in the 70s, so it’s great to see it moved on.

“The city deserves that.”

Conversation