Plant hunters were hardy characters, explorers who in a period from the 16th to 20th centuries were being sent all around the world, in search of new plant, to countries opening up their borders.

They could be working for plant nurseries or wealthy owners of grand houses wanting their garden to be the first to have the latest exotic discovery.

Seeds, cuttings and live plants were also being sent back for scientific study. Botanical gardens around the country, including St Andrews, Dundee, Aberdeen and Inverness are home to magnificent collections of plants from these adventurers, today also being used for education and conservation projects.

I didn’t learn about plant hunters and their adventures until I went to work at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh. Rhododendron and Primula from Chinese hillsides collected by George Forrest, mountain plants from the travels of Reginald Farrer. Even today where I work at Scone Palace the grounds are home to one of the first ‘Douglas Firs’ in the country grown from seed sent back by the great man himself, David Douglas.

The stories of their adventures fascinate me, this may sound an idyllic occupation strolling around picking flowers all day but actually it was far from it. Plant hunters were poorly paid needing to rely on their ingenuity, negotiation and hunting skills to survive.

Getting to their expedition destination meant months travelling by boat before even starting work and then many miles more were walked climbing up mountains and back down again into the valleys in search of these new plant species.

Some times the local peoples would take kindly to them while others would treat them with suspicion, intending to hunt them down and kill them.

I tell you what, any big-shot Hollywood producers reading this and looking for an idea for their next blockbuster should be looking no further than the stories of these guys!

Over the years I have become familiar with the more ‘big name’ plant hunters but there are many more of Scottish origin who have made equally notable plant introductions for us.

Thomas Thomson is one such plant hunter, born in Glasgow on December 4 1817. He studied medicine, eventually setting sail to India as assistant surgeon for the East India Company however it was his friendship with classmate Joseph Hooker that would ultimately shape his life.

Jospeh was the son of William Hooker who’s energy and enthusiasm helped revitalise Glasgow Botanic Gardens in his role as Professor of Botany. He clearly had a positive influence over a young Thomson who wished botany to be a significant part of his life, also using his stature to redirect Thomson as curator of the museum of the Asiatic Society on his arrival in Calcutta.

Suddenly he was removed from this quiet life to accompany the British India army on a gruelling 10-month march to Afghanistan, taking advantage of this journey to roam amongst flora previously unknown in Europe.

Battle could not be avoided forever and he was eventually caught up in one of the most violent of the Afghan wars, somehow surviving a massacre of nearly 15,000 people. He had been captured possibly heading to a fate worse than death being destined for the slave markets, but managed to negotiate his way out of this situation with bribery.

Eventually the far reaching arms of William Hooker were to rescue Thomson out of the army when he was appointed one of three commissioners to define the boundary between China and Kashmir. Whilst carrying out this task he was also to report on anything of interest, concentrating on botany in an area virtually unexplored on the edges of the Zaskar Mountains which stretch to Nepal and Bhutan.

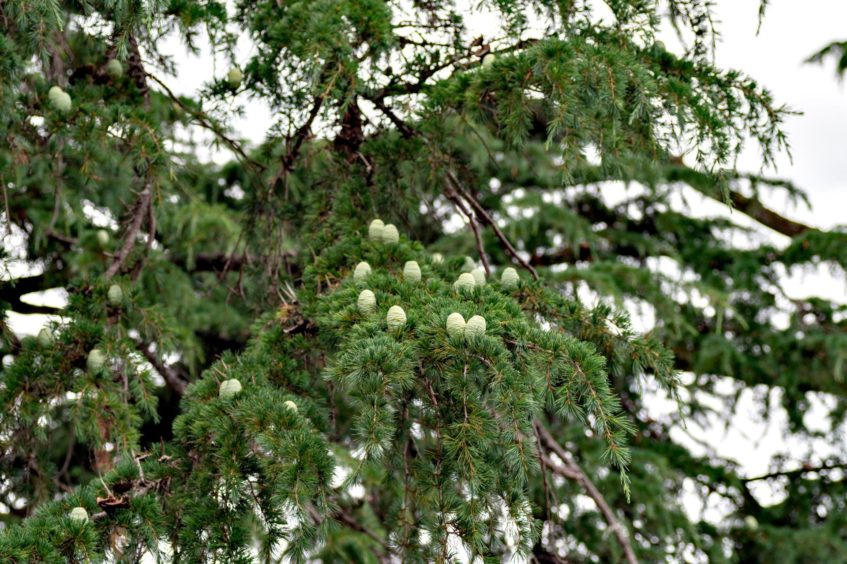

It was here, growing in the many temples he passed that he saw the elegant, hanging down branches of the Himalayan Cedar, the green needles tinged with a hint of blue.

Whilst preparing to return home he heard news that his childhood friend Jospeh Hooker- who was to become a close friend of Charles Darwin and director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, had been travelling in the eastern side of the Himalayas. The pair reunited and over the next two years explored the plant rich Sikkim forests.

Other plants he introduced familiar to us include Fritillaria imperialis, a bulbous plant producing a leaf-topped flower spike around 1 metre/ 3 foot tall, the flowers coloured orange, yellow or deep red. This is also known as crown imperial referring to the circle of flowers resembling an emperor’s crown. Also the wonderful Primula denticulata whose flower head is shaped like that of a drumstick, my personal favourite among lavender coloured flowers.

Botanists today must apply for strict permissions before embarking on any plant expeditions to another country, a protocol helping to protect plant material from being exploited or in extreme cases becoming rare in it’s natural habitat or even extinct.

It’s worth noting that even in our own country it is illegal to dig up wild plants such as snowdrops and bluebells without the permission from the landowner.

Wee job this weekend

Every plant in our garden has a fascinating tale behind it. Choose a favourite from your own or public park and do a little online research to discover more about the hidden story it has.

Brian Cunningham is a presenter on the BBC’s Beechgrove Garden, and head gardener at Scone Palace. Follow him on Twitter @gingergairdner