Gayle hikes up the Caterthuns – the remains of two Iron Age forts steeped in history and legend.

An impressive iron age hill fort crowned by a mass of pale stone rises up from the ground a few miles west of Edzell.

Standing in the centre of the giant circle of tumbled rocks, I drink in stunning views across the Angus Glens, Aberdeenshire and beyond.

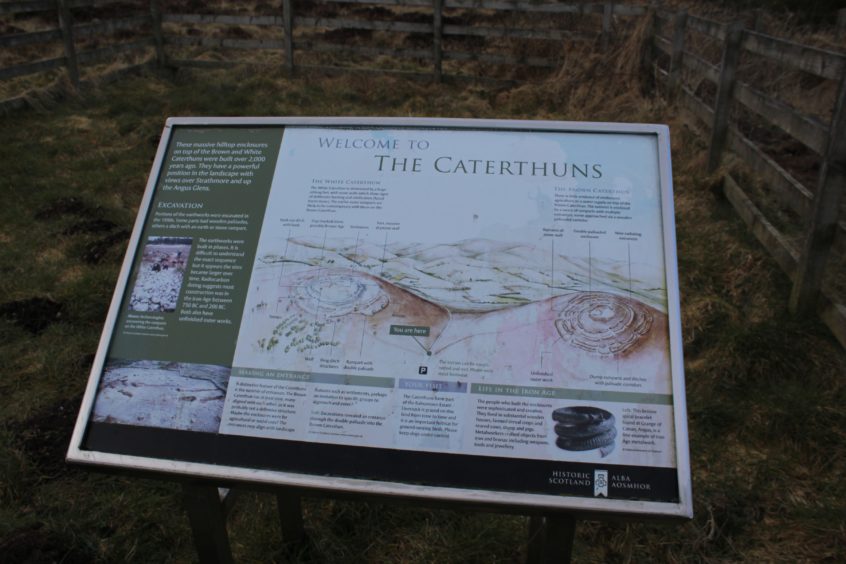

The White Caterthun, as this landmark is known, is a stone’s throw from its sister fort, the Brown Caterthun, which lies beneath a dark mantle of heather.

A colourful patchwork of fields dominates the landscape in all directions and wisps of smoke emanate from distant hills, evidence of muir-burning, a practise which encourages heather to produce new green shoots for grouse.

Nobody knows exactly what the Caterthuns were used for but it’s tempting to imagine them as tribal forts or perhaps places of worship.

They’re steeped in myth and legend and one of the best stories, in my opinion, involves a witch.

Yup, apparently this mystical figure, no doubt festooned with warts and a crooked nose, took a mere morning to carry the stones used to build the White Caterthun’s fort up to the summit in her apron.

A string was said to have broken as she flew through the air and one stone dropped out of the apron and landed in a field, transforming into a standing stone. I love it!

There’s a rather grim story about the Caterthun fairies, too.

These sinister wee things, said to have lived in a huge cave under the forts, stole a baby from a couple who lived in the nearby hamlet of Tigerton.

The baby, once returned to his mother, began to waste away and locals deduced he was a changeling.

To test whether the child was fairy or human, he was held over a gorse bush while it was set on fire. If he’d been of fairy stock he would’ve flown off back to his native realm under the hills.

However, the unfortunate baby was, indeed mortal. He screamed as he received a “slight burn” and was handed back to his distraught mother.

The folk tales don’t stop there. A well on the west side of the White Caterhun was rumoured to contain a kettle filled with fairy gold.

Whether or not you believe any of these tales doesn’t matter but it’s worth knowing that the Caterthuns are among the best-preserved iron age forts in Scotland and deserve a visit.

Access is from a minor road that passes between them en route to Bridgend.

It takes about an hour to dash up and down both Caterthuns – they’re about a kilometre apart – but you’re best to allow more time to savour the views and perhaps even enjoy a picnic.

It was a rather chilly day when I explored the remains of the forts and apart from the glorious views, it was somewhat bleak, prompting me to imagine what life must have been like for the Iron Age inhabitants.

A jug or two of ale, some deerskins wrapped round their shoulders and a bubbling pot of stew on a roaring fire would have made things bearable I suppose.

Unsurprisingly, there are conflicting theories about the age, construction and use of the Caterthuns.

Both are enclosed by a series of earthworks, and it’s likely they served both as military and ceremonial centres.

Certainly, the White Caterthun, so named because of the “white” stones used in its construction, seems to have functioned as a settlement.

The stones have tumbled from two concentric walls, which must have been a breathtaking sight in their heyday.

The inner wall alone was 12m thick and several metres high, enclosing an area of around two acres. Today the boulder mass is spread over around 30m.

A hollow in one corner has been identified as the location of a rock-cut cistern that held the fort’s water-supply, but there’s no sign of water here now.

Some surmise the Brown Caterthun, which is formed of earth embankments, was a religious centre.

It’s not as impressive in scale as its white counterpart but it does boast an unusual feature – causeways marking nine entrances, perhaps evidence the fort became a site for medieval fairs.

If it wasn’t a witch who built the Caterthuns, then it must have been brawny men with rudimentary tools such as picks and shovels.

Excavations at the Brown Caterthun in the 1990s found little evidence of occupation.

But they did reveal the site increased in size over time, and that its ramparts were burned, rebuilt and re-modelled in several phases.

Radiocarbon dates from excavations on the Brown Caterthun show it was constructed between 700BC and 200BC.

Meanwhile, the White Caterthun shows evidence of vitrification – a process in which stones are fused together due to intense heat.

While walkers like myself tend to view the Caterthuns as two sites – they’re bisected by the road – it may have been that they were considered as one site with two summits. Who knows.

For a double whammy cardio-boosting hike boasting epic views and a wee bit of history, you could do a lot worse than heading up the Caterthuns… when lockdown allows.

- Please observe government coronavirus safety guidelines in all outdoor activities.