Gayle joins a ‘crannog cruise’ on Loch Tay and discovers the secrets of these ancient islands.

Loch Tay is a magnificent, dark stretch of water, 15 miles long and more than 500ft deep in parts.

Flanked by the towering bulk of Ben Lawers to the north, the loch is in a remote, peaceful setting, enjoyed by watersports enthusiasts, locals and tourists alike.

It’s hard to imagine that hundreds of people once lived on the loch, inhabiting ancient manmade islands known as crannogs.

There are thought to be 18 on Loch Tay and while most are submerged, there are a few which can still be seen, appearing as tree-covered islands.

I’ve come on a special crannog cruise, hosted by Loch Tay Safaris and the Scottish Crannog Centre, in a bid to find out more about these curious creations.

Skipper Stuart Brain and crewman Norman Brett are accompanied by Crannog Centre guide Rich Hiden, who’s rocking an Iron Age-style tunic and has a scary-looking dirk tucked into his trousers.

There are another five folk on board, and with covid-related restrictions in force, that means the swanky 12-seater vessel is at full capacity, for now at least.

As we head up the loch, Stuart, Norman and Rich regale us with fun and fascinating facts.

“The history of Loch Tay is as deep as its waters,” beams Rich.

“One of the most mysterious features is the handful of islands in the landscape.

“The secrets of these islands have been investigated by archaeologists for decades.

“During this trip we want to get you as close to the history, prehistory and archaeology of these crannogs as possible.”

In 1979, a survey was made of crannogs on the loch, with the Iron Age site of Oakbank Crannog, off the village of Fearnan, being selected for pioneering underwater investigation.

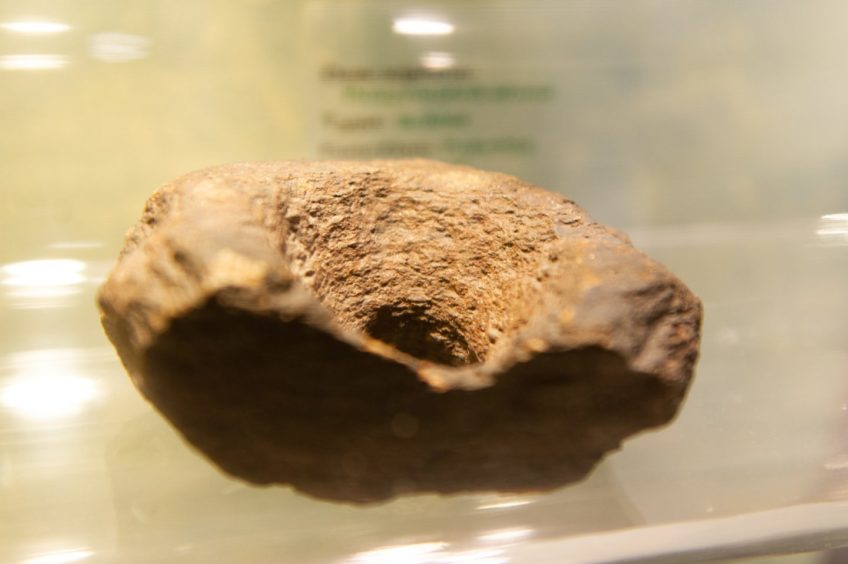

Excavation revealed well-preserved 2,500-year-old structural timbers, domestic utensils, remains of food and textiles.

These fantastic finds inspired the project to build the dedicated Crannog Centre, on the opposite side of the loch near Kenmore.

We pick up speed as we head towards wooded Priory Island where Norman takes up the story.

“Queen Sybilla died on the island in 1122 and Clan Campbell built a fort there in the 16th century, the ruins of which still stand today,” he explains.

“It’s also known as ‘Island of the Women’ because nuns lived here. They came ashore once a year to sell their wares and get drunk! Their lewd practices, chasing men and the like, were legendary!”

Long before the nuns came along, Priory Island started life as a crannog joined to the shore by a causeway.

Today it’s Loch Tay’s most visible example of the ancient dwellings.

Further north at Dalerb, Rich tells us about exciting plans to create a “crannog community” here by 2025.

This will see the current Crannog Centre, built between 1994 and 97 and boasting a reconstruction of a crannog, being relocated and expanded.

The new site, which Rich describes as a “national museum” will boast an Iron Age village and three new reconstructions of stilted loch dwellings.

As we putter out into the middle of the loch, Stuart tells us the story of the Loch Tay Kelpie.

Apparently, this mythical water horse can take on the form of a handsome man.

Inviting everyone to feed him some oats, we scatter handfuls over the edge of the boat in the vague hope something might appear.

Neither man nor beast shows up but what this wee exercise shows us is just how clear the water, which had appeared to be completely black, is.

The oats seem to turn gold as they sink down into the loch, and we watch, mesmerised, as they vanish into the depths.

Magic oats and kelpies aside, what excites Rich most is Oakbank Crannog.

“It’s possibly the best archaeological site for understanding life in Britain 2,500 years ago,” he enthuses.

“A scrap of twill, a stringed instrument, a type of spelt and a butter dish from 500BC with remains of butter on it were discovered here.”

Other artefacts, some of which can be seen at the Crannog Centre, such as a foot plough, wooden utensils, a whistle, animal bones, fruit, nuts, and plant remains offer evidence of a farming lifestyle.

Many crannogs were built in the water as defensive homesteads and represented symbols of power and wealth.

Once abandoned, the structure would eventually rot away and keel over, crumbling down on top of all the debris that had dropped into the loch.

A combination of lack of oxygen, no light and cold water are the main reason why they have been preserved.

Heading back down the loch, Rich challenges folk to see if they can spot another crannog.

“Bear in mind the translation of the word ‘crannog’ – crown of a young tree, more or less,” he offers.

It’s small but not tricky to spot, a stony mound bursting up through the water; a tiny islet topped with a cluster of trees and covered in dense vegetation. It’s a real treat for the eyes.

Check out any OS map of Perthshire or the Highlands and the chances are you’ll spot crannogs in most lochs – just look for the wee dots.

Hundreds have been found in Scotland but only a few have been investigated.

Whether you’re a local or a tourist, a crannog cruise is a fantastic means of learning more about the area, its ancient history and its people.

- Loch Tay Safaris and the Scottish Crannog Centre are collaborating to offer special cruises to celebrate VisitScotland’s Year of Coasts and Waters.

- Crannog Cruises, featuring guides dressed in Iron Age costume, run on Wednesdays at 2pm until June 23.

- Passengers can then visit the Crannog Centre. Advance bookings at lochsafaris.net.