Covid-19 lockdowns saw more people explore their local coast and countryside. However, this occasionally brought unprecedented, chaotic and hugely disruptive pressure to rural areas. As restrictions ease, Michael Alexander explores the positive and negative impact.

When the Fife Coastal Path was recently ranked in the world’s top 20 Instagrammable hiking trails alongside the likes of the Appalachian Trail in West Virginia and Peru’s Machu Picchu, it came as no surprise to locals familiar with the dramatic landscapes of Fife’s “fringe of gold”.

But with visitor numbers increasing dramatically to local beauty spots during the Covid-19 lockdowns, an appreciation for the beauty and elegance of what’s on our doorstep was countered by a spate of wild camping, littering and access problems.

Massive peak

Fife Coast and Countryside Trust (FCCT) communications officer Audrey Peebles says it’s “nothing new” for the Fife Coastal Path to appear on ‘best of’ lists.

However, there’s no doubt that the “massive peak” of local visitors – especially during the first lockdown of 2020 – helped raise its profile, and the hope is that this appreciation for local destinations will continue.

“Anybody that’s enjoyed a staycation who might not traditionally have done so – we hope they further appreciate how beautiful Fife is,” she says.

“Our award winning beaches – known as the fringe of gold – are stunning.

“So hopefully it’s opened their eyes to fascinating beautiful places that we are lucky enough to live in.”

Data, measured by FCCT’s people counting equipment, speaks for itself.

At the Newburgh end of the Fife Coastal Path, visitors were up 44% in March 2020 compared with the March previously. By April, they were up 62% and by May they were up 90%.

At Ardross, near St Monans, visitors using the path were up 78% last July and August while in Kirkcaldy, walkers along Seafield and the Promenade rose by 138%.

In July 2020, for all the sites that could be measured, a total of 183, 883 visitors were recorded.

Despite people going back to work and being able to travel elsewhere, numbers have remained high – especially on the beaches.

Challenges

The influx of people has, however, brought other, well-publicised challenges.

During the first lockdown, the Lomond Hills were “just mental” with visitors “hundreds of per cent up” causing problems when car parks overflowed and some parked irresponsibly.

There have also been challenges caused by wild camping and increased levels of littering.

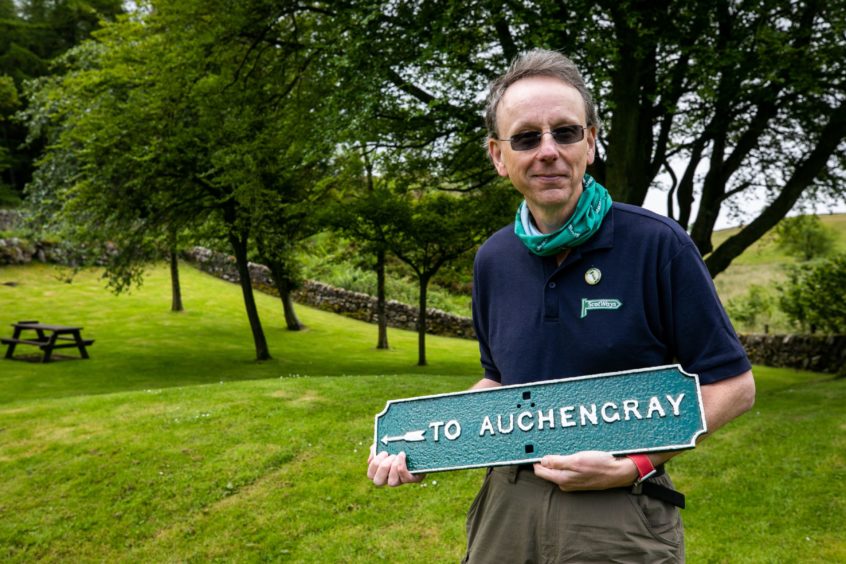

Richard Barron is chief operating officer for ScotWays (The Scottish Rights of Way and Access Society) – the independent charity which upholds and promotes public access rights in Scotland.

He says some of the problems experienced at beauty spots across Scotland – especially during the first lockdown – exemplified a “selfish me first” approach to life by some individuals.

However, he says if there’s one positive to have come out of the pandemic, it’s that more people have got out and about in their local areas to responsibly discover the beauty of the countryside.

“There’s no doubt it’s been a really odd time,” he says.

“What we’ve seen is people who were always prepared to go walking – the ones who would go mountaineering, drive from Edinburgh to the Cairngorms –they were feeling quite restricted in where they could go.

“You then had a second group – the ‘I always holiday in Ibiza’ folk – who also had to change.

“There’s been some places where a lack of people has really helped nature to bounce back. Those tended to be the places away from settlements.

“But you then saw local places around communities suddenly having this massive uptick in people wanting to literally get out there and just enjoy the countryside.

“That was a positive. The downside was you were having landowners thinking ‘holy hell where’s all these people come from?’”

Right of access

Under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, new rights of responsible public access to land and the countryside were introduced, meaning people had a legal right to be there, so long as they act responsibly.

However, instead of “one or two walkers a week”, problems were arising when there were suddenly “20 or 30 a day”.

Richard said particular problems arose early in lockdown when, amid concerns that Covid-19 was transmitted through droplets and touch, some landowners would lock gates barring public access.

Another problem arose when people “not used to being in the countryside” started dropping litter.

Add to this the furloughing of council and ranger staff, and when complaints needed to be investigated, it meant that in the early days, problems couldn’t always be resolved immediately.

This, however, was just the start.

“In the early days of proper lockdown, everyone was finding their feet,” he says.

“But when lockdown started to ease, and you didn’t have overseas travel, new problems arose. For example, you had people going to Loch Lomond with their £10.99 festival camping kits. They’d cut the trees down, have a barbeque and campfire and leave all their mess.

“One of the places that really had a problem with cars was up in Aberdeenshire at the Cairngorms.

“At Braemar, you had people finding the Linn of Dee car park was full, and everyone was parking on the road. That’s similar to what happened in Fife at the Lomond Hills.

“It’s symptomatic of ‘as a person what I’m interested in is me. I’ll do what I want to do when I want to do it. I’ll go for a walk, go for a bathe, and I’ll just park on the corner here’.

“That sort of selfishness exasperated the problems. Yet if people had a ‘plan B’ it could be avoided.”

Positives

Despite these problems, Richard said another positive to come out of the pandemic was that as awareness grew, agencies like NatureScot, VisitScotland and Police Scotland started to engage more.

Richard was also struck by how, that after 30 years of campaigning to improve outdoor access and promote the physical and mental health benefits of getting out and about locally, the pandemic had “forced” people to discover it for themselves.

“In the space of a month we had everybody walking locally which is something we’ve been trying to do for decades,” he laughs.

“That was a massive plus as people explored their local area – even though you had the problems for landowners.

“We’ve got climate change on the agenda, local travel means less CO2, less traffic – all those huge strategic things.

“But the pandemic has also helped tackle other existing problems. The North Coast 500 for example. A fantastic route and amazing marketing but really crap facilities that caused problems for locals.

“The Fairy Pools on Skye, Devil’s Pulpit at Stirling – these really popular places but again didn’t have the facilities.

“What Covid did is get governments to think about it, to get councils involved. It’s banged peoples’ heads together. We’ve ended up with a tourism revenue fund. What we’ve got to do now is keep the pressure on to keep that happening.”

Ancient routes

While some destinations are well trodden, the pandemic has also led more people to explore local, more obscure, routes often tied in with local history.

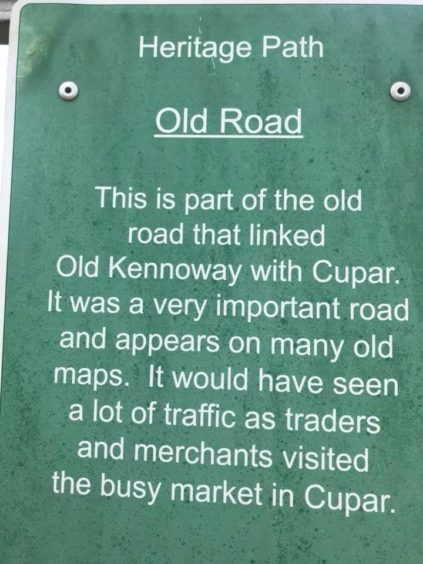

Fife examples include the ‘Old Kennoway Road’ running from near Cupar towards Chance Inn, the Waterless Road which was the old road between St Andrews and Ceres which is now part of the Fife Pilgrim Way, and the Stratheden path near Springfield where information boards explain that after a murder in the early 1960s, the road was closed off to Travellers.

The Coronation Road was the route royals travelled between their palaces at Scone and Falkland, while in the Highlands, hikers can marvel at the history of the battle of Glen Tilt, as it became known.

Here, a dispute over a right of way between Edinburgh botanist John Hutton Balfour and the Duke of Athole in August 1847, led to the setting of an important land access precedent.

Mile markers

Often, however, it’s the history of signs and mile markers themselves which capture the imagination.

The Romans take credit for first introducing roads and signage to Britain to aid the movement of soldiers and supplies.

They possibly marked every thousandth double-step with a large cylindrical stone. The Latin for thousand was ‘mille’ and the distance was 1618 yards.

The eventual British standard mile was 1760 yards, although ‘long’ miles also existed into the 19th century. After Roman times, roads developed to meet local community needs.

Turnpike roads were eventually developed to overcome sunken lanes that often became quagmires.

From 1767, mileposts were compulsory on all turnpikes, not only to inform travellers of direction and distances, but to help coaches keep to schedule and for charging for changes of horses at the coaching inns.

Milestone Society

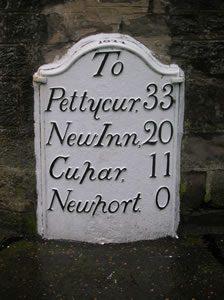

Today, the Milestone Society lists the country’s surviving mile markers.

These are listed as anything marking the miles (as required by the various individual and general Turnpike Acts), within which there are ‘classic’ milestones of stone and generally later mile plates/mileposts of cast-iron.

Angus has a fair number of surviving milestones, as well as unusual ‘giant spike’ mileposts by George Anderson of Arbroath and Carnoustie.

It’s in east Fife, however, that some of the best surviving examples in the country can be found.

“In the time before mass production there were endless variations in design produced by local craftsmen, some quite remarkable,” explains John Riddell of the Milestone Society.

“It is surprising how many survive – often partly buried and hidden in the vegetation – with unknown ones still being found quite frequently.

“During World War Two in 1940 as part of preparations for the expected invasion, the government instructed all road signs to be removed.

“This usually involved ‘defacing’ milestones, and removing cast-iron mile markers most of which disappeared into the wartime scrap-metal effort.

“However the Eastern District of Fife has probably the best collection of surviving mile plates in Scotland. These were carefully conserved during World War Two and in modern times.

“Fife also developed the unique ‘Fife Cap’, a cast-iron cap fitting upon a granite milestone.

“In addition there are historic cast-iron way markers at junctions, giving directions to local destinations.

“A good deal is known about the local foundries which produced these castings, the earliest established date being Alex Russell of Kirkcaldy 1824.

“There are also classic milestones surviving elsewhere in Fife, with some rare mileposts produced in Falkirk foundries.

“These mileposts are rather vulnerable to theft, hence ongoing discussion about safeguarding them.”

Evolution of roads

The mile markers of Fife are a big subject, reflecting the complex evolution of the roads network from the agricultural revolution and as new industrial harbours were developed along the Forth.

Some of the old roads became disused and are now no more than faint tracks across the fields. Other old routes, meanwhile, have been consumed by more modern infrastructure.

George Robertson, honorary president of the Dunfermline Historical Society, has been researching the story of Thomas Henry Tuckett, who surveyed the roads of West Fife during the mid-19th century. He will soon publish his findings on the DHS website.

George has also researched the Great North Road between North Queensferry and Kinross alongside co-author Eric Simpson of Dalgety Bay.

Starting at North Queensferry , the Great North Road went through Inverkeithing, followed the route of what is now the M90 up to Crossgates, initially to Kelty, through Blairadam then up as far as Kinross.

Their main thrust was to investigate what infrastructure still existed in terms of toll houses, inns, change inns, milestones and blacksmiths.

“Peoples’ lives were very much integrated into the infrastructure – there’s no question about that,” he says.

“But while only parts of the infrastructure remain, the roads themselves often live on.”