As the summer harvest gets into full swing, combines can be seen tearing through bumper crops of ripe wheat, barley and oats across the country. Gayle Ritchie explores harvesting through the ages…

Cotton wool clouds drift lazily across a blue-grey sky, casting shadows on the golden fields below.

A huge combine harvester lumbers through acres of wheat, the gnashing teeth of its cutting bar slashing down everything in its path.

Clouds of dust and chaff whip up behind the growling machine, and a blackbird reels into the sky, shrieking in dismay.

This is the height of harvest season, a highlight in the farming calendar, when what has been sown can finally be reaped.

It’s an exciting and busy time, with farmers burning the midnight oil to bring in grain between downpours.

When I turn up at a field near Drumgley in Angus to watch John Grant harvest wheat, he invites me for a ride in the cab of his combine.

As we trundle along at around 4kmph, John, who works for Arable Ventures, tells me he’s preparing for an epic 18-hour shift.

“I got to bed at 2am last night,” he says, rubbing his eyes. “We’re trying to get through around 100 acres a day, so let’s hope the rain stays off.”

The combine harvester of the 21st Century is a magnificent beast, and the one we’re in today cost around £300K and boasts auto-steering and GPS.

It’s somewhat unnerving as John takes his hands off the wheel and roots around for an antihistamine to give me (I’ve just been stung by an angry wasp).

Without getting too technical, the combine does what it says on the tin – a combination of jobs, but by and large, it cuts the stalks of grain, threshes and thereby separates the straw from the grain.

The grain is then taken to a dryer, stored, and if it’s wheat, it’s sent to a distillery or used for bread, biscuits or animal feed.

While mesmerising to watch, harvesting, as with many aspects of farming, can be a dangerous business.

Stories abound of combine-related tragedies, and Jim Herron, former farm manger of Kinnettles estate, fell victim to a machine’s jaws in 1986.

Stepping down from the cab, I leap over a mound of straw to greet him.

Evidence of his accident is clear to see – he’s missing his right arm up to the elbow.

Jim, a lithe, tanned, bright-eyed 79-year-old, takes up the story.

“We were harvesting peas and the combine clogged,” he recalls. “Normally we’d shut off the machine but for some reason, the engine was still going.

“I put my hand in to clear it as the other lad switched the combine back on. My hand was all chewed up; there was a finger here, a finger there.”

Born in 1938 in Kirkbuddo, taking on the role of farm manager at Kinnettles from 1972 to 2000, Jim has witnessed major changes in farming practice.

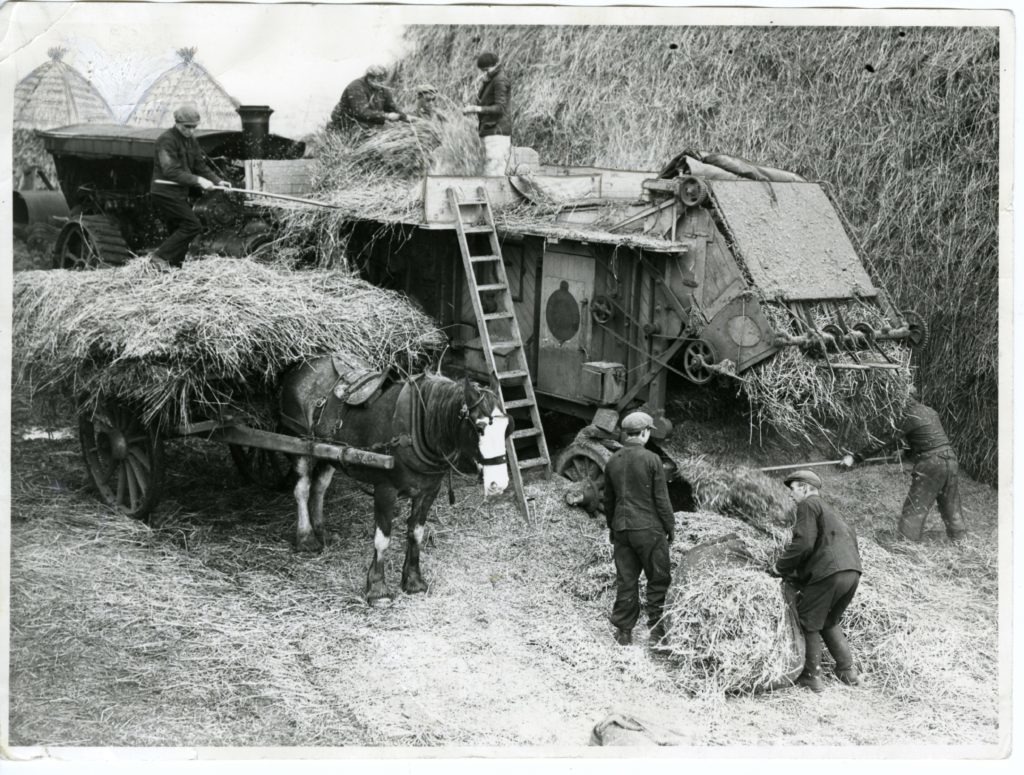

He recalls both his father and grandfather using scythes and horses to bring in the harvest.

“In the 40s, men would go round the outsides of fields with scythes, cutting the crops, and I was helping from the age of 10.

“Lads would gather bundles and tie it into sheaths. We’d thrash, or tramp the grain in the barn on Monday mornings and went into school late.”

Horses pulling binders, which cut, tied and dropped bundles of cut crop, were a common sight. This, in Jim’s mind, was one of the hardest jobs the animals had to do.

The crop was harvested in its entirety (straw and grain) and then stood in stacks (also called stooks) like little tents, to dry out.

The last horse Jim’s father had was in 1951 and after World War Two, there was a huge surge in tractors.

“They flooded in from the USA and everything was speeded up with mechanisation,” he recalls.

“My father offered the horseman a tractor but he was dedicated to horses, as many were, and some kept horses until they were in their 70s.”

When combines came along they made life much easier, and grain was separated from straw in one swift move.

Jim drove combines from the age of 15 but the machines of the early 50s were nothing like those of 2017.

“Back then, they had an open cab so dust was flying everywhere!” he beams. “And while they had a six-foot cutting bar, these days they can be 32ft.”

While reflective about change, Jim is not sentimental. “A lot’s been lost but that’s progress,” he says, matter-of-factly.

“There’s an old saying, ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ and that sums it up.

“Lads are out in tractors all day on their own these days; they never see anybody. When we did things by hand, it was hard work, but we did it in squads, in big groups, and it was a lot of fun.

“There was always a comedian among us, cracking jokes. With machinery, we’ve lost contact with people.”

It was Euan Walker-Munro’s father who offered Jim the job back in 1972, and these days, Euan farms at Kinnettles, although he is less hands-on, finding himself up to his neck in admin and working with drones to survey crops.

“You think of the harvest as being the end of the year, but the farming year never stops,” he says, joining us as the sun breaks through the clouds.

“Right now, in another field over the hill, crops are being sown for next year.”

Euan has been at Kinnettles since 1968 and his family came to Angus in the mid-1800s.

He recalls a lot of noise from whirring machinery and stoor (dust) when he was a young lad.

“There was less health and safety so we rode in bogies and sat on top of the grain as it was taken from field to dryer, and played in stacks of straw bales.”

Like Jim, Euan is not misty-eyed – “farmers tend not to be; they tend to be progressive,” he says.

“But there’s been major social change in the countryside and up to 90% of the workforce has gone.”

Despite the changes in harvesting, the essential job remains the same – getting the grain off the “ears” and into sheds – but machines continue to increase in size, safety has improved and manual labour has reduced.

“Technology is there to increase accuracy, so reducing costs both financial and environmental, and also fatigue on operators,” says Euan.

Today, across Kinnettles and Lindertis, the two estates Euan is involved with, there are only three full-time men working. In the early 70s this number would have been closer to 30.

What Euan loves most about the harvest is the fact it’s the culmination of the year’s work and the sense of relief once it’s stored in the shed is huge – “although ultimately, the job is only finished once the cheque is in the bank!”

Along the road at Kirriemuir, surveyor David Orr, 69, has dug deep into the history of harvesting, and is president of Abertay Historical Society.

His father, also David, ran the family farm, at Denmill.

“Back in the early 1800s, folk from the Highlands would come down to Angus for the harvest; they made income working on arable land,” he says.

“They lived in uninhabited castles, such as Kellie Castle and Inverquharity.

“They would use a sickle, or heuk – an early version of scythes – to cut the crop, and then bound up the sheaves or stooked them.

“By the mid 1800s, Patrick Bell from Carmyllie had invented the binder and everything changed.”

While David is unsure whether to welcome the concept of driverless tractors, he is reluctant to romanticise harvesting “in the olden days”.

“Folk like to look back wistfully but it’s worth remembering it was back-breaking physical work,” he says.

“The harvest of days gone by had a strong community feel, a community spirit, with families coming from all over the country to help; there was always a huge sea of people in the fields.”

Coming back to John, who has a good 17 hours left of combining before he heads to bed, I ask if he gets lonely in the dead of night, with only a radio and his mobile to keep him company.

“Never,” he replies. “Because I love it. You’ve got to put your heart and soul into this, or don’t do it at all.”

Later in the day, I go for a run as darkness is falling and first hear the low rumble of a combine, and then see the twinkle of its headlights.

It’s a magical, mesmerising and strangely comforting sight.