A year ago I came to Dundee as part of a programme of visits across the UK organised by the Bank of England, where I am one of the Deputy Governors.

It’s important that my colleagues and I who make economic and financial policies that affect us all get out and see what’s happening in communities up and down the country.

Our Community Forums are designed to give us a slightly different perspective on the health of the economy from the official statistics and even the meetings we have regularly with businesses.

Instead we view the economy through the eyes of charities and the people they support.

This month I returned to Dundee – not physically, of course – but via the wonders of modern technology.

But our video call did at least give me the chance to catch up with the leaders of Dundee’s charities and listen to their take on the current unprecedented situation.

The Covid-19 crisis makes these events even more important than they always are.

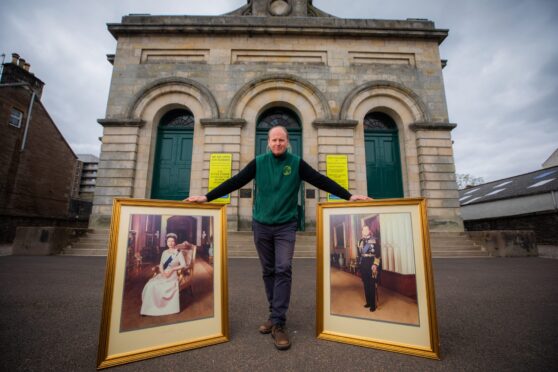

When I was actually in Dundee last year, I visited some absolutely inspirational charities.

These included the Main Street Café, a community initiative for people struggling to afford food, and the Hot Chocolate Trust, which supports the city’s young people to develop their own opportunities.

It was painfully obvious across these visits how up until recently some people in Dundee were still feeling the effects of the financial crisis of 2008 – with foodbanks, in-work poverty and fuel poverty among the issues being dealt with by the city’s charitable organisations.

The team and I felt we should revisit these issues as we face another crisis in real-time.

Dundee has been hit hard by Covid-19. It has one of the highest death rates in Scotland. Unsurprisingly therefore the challenges faced by the organisations I spoke to are particularly acute at this time.

During the meeting I heard that lockdown, necessary though it is, has exacerbated some problems and inequalities that were already serious before the pandemic hit.

Worryingly but unsurprisingly, severe mental health difficulties in vulnerable young people are worsening in this stressful time – and uncertainty about both the near and long-term future is adding to this.

Concerns were expressed about the employment situation in Dundee – in particular the numbers of people who were in precarious forms of employment before the pandemic and are now unable to work, but who are also not receiving support through the government’s furlough scheme.

There was a feeling that social inequality is widening, and heightened worries about whether the population of Dundee will be able to upskill as needed through and after the crisis.

The thing that strikes you at these sorts of meetings is really just the most obvious thing: the level of unemployment has been low in recent times, but that doesn’t mean the system is working well for everyone.

We mustn’t let healthy aggregate statistics allow us to become complacent. And the Covid crisis is likely to hit both the aggregate and the local in nasty ways.

If this all sounds depressing, well, it is a tough situation.

But on the other side of the coin, there are many incredibly energetic and innovative people working very hard in the third sector in Dundee in order to cushion the blow for others.

I found it interesting to reflect on the comparison with our own role at the Bank of England: we’re working deep in the plumbing, in a way that affects the entire economy in a very significant way.

Third sector colleagues in Dundee have a similar aim, but are working way downstream of us. All strength to their arm.

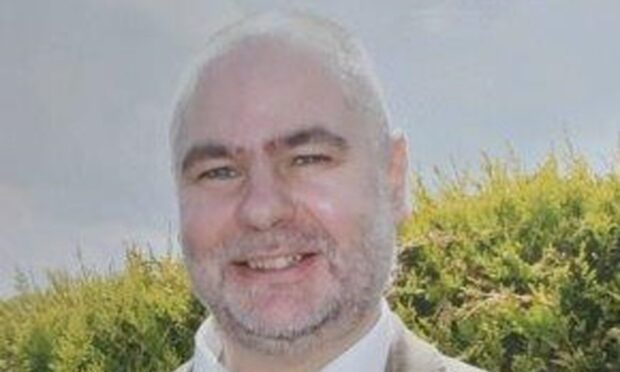

Sam Woods is Deputy Governor for Prudential Regulation at the Bank of England