A grandmother has shared her emotional story of losing her teenage grandson to suicide in the hope it will encourage young people to open up about mental health.

Matilda Thomson says her grandson Ragan rarely spoke of his own issues despite being troubled over the death of his mum, Marilyn Thomson.

Matilda’s daughter, Marilyn, was murdered by her husband in her own home as her four children slept in their beds upstairs.

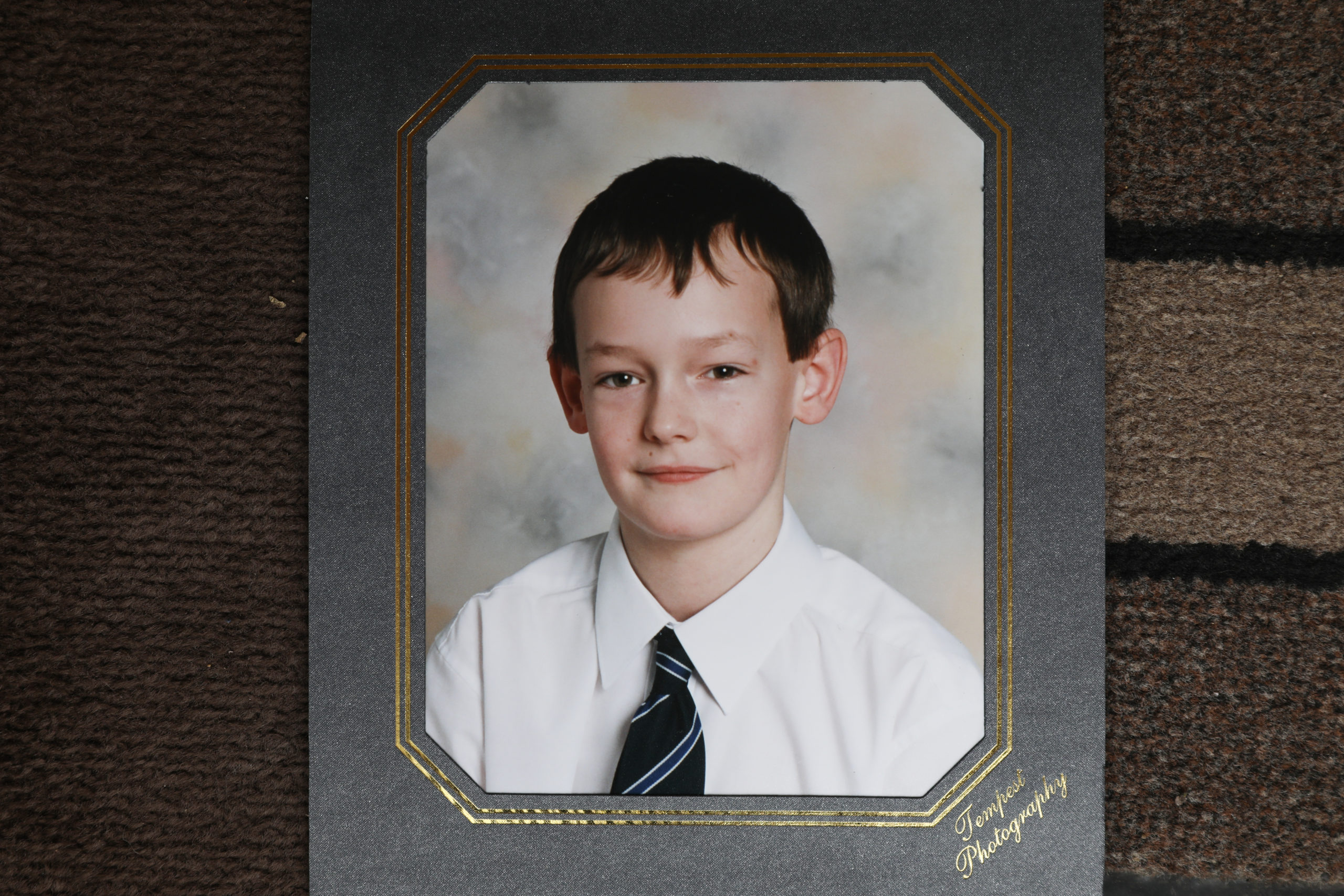

Ragan was just three years old at the time and silently carried the pain of losing his mum for 15 years before taking his own life.

Marking the tragic ten-year anniversary of Ragan’s death this month, Matilda has spoken out for the first time.

It was an average Friday evening in the summer of 2010.

Ragan Thomson said bye to his gran, Matilda Thomson, in his usual way – giving her a cuddle, rubbing her head and saying he loved her.

The 18-year-old then left the home he shared with his gran in Lochee and visited his sister at her house, before going to town to meet friends.

At some point in the evening he phoned his gran and asked her to look out his passport which he needed to start a new job at Halfords that weekend.

Matilda found his passport and set it down on a table for Ragan to collect when he came home.

But he never did.

Matilda got a knock at the front door in the early hours of Saturday July 3.

Two police officers told her to sit down before explaining that Ragan’s body had been found at a wooded area off Kirk Street, having taken his own life.

Matilda said: “I didn’t believe it. I said it couldn’t be Ragan, they must have it wrong, he wouldn’t do that.

“I can’t describe the feeling, it was utter disbelief. Sometimes I still can’t believe it. It just didn’t seem like him, no one believed he would do that.

“When it sank in, it hurt. They’re my grandchildren, I was supposed to take care of them. ”

Matilda says Ragan never spoke about his mental health and found it difficult to open up about his feelings, but that deep down he was “troubled” about losing his mum.

Ragan’s mum, Marilyn Thomson, who was Matilda’s daughter, was strangled and stabbed to death by her husband James Briggs, father to Ragan and his brother and sister.

The murder took place at Marilyn’s home on Kirk Street in 1996 while all of Marilyn’s four children slept upstairs.

James, known as Jimmy, did not live with Marilyn, 29. The pair had what Matilda describes as a “toxic” on/off relationship due to Jimmy’s obsessive behaviour.

The morning after the attack one of Marilyn’s daughters, aged nine, found her lying on the floor with a blanket on top of her and asked her to get up.

When she did not respond, the child ran to a neighbour’s for help then to Matilda’s home, just across the road at Elders Court.

Matilda said: “When we went in the house there were paramedics there and Marilyn was lying on the floor. I went to go to her and they told me not to touch her.

“I didn’t see a mark on her. I’ve been told there was but I didn’t see it, I must’ve been in shock.

“I don’t remember much after that but someone told me I was upstairs making the beds, because Marilyn liked to keep things tidy, and a police officer came in and said ‘Marilyn’s dead’.”

That night Matilda took the kids home with her, the youngest who was nine-months-old, and raised them on her own.

She says all of the children struggled to come to terms with what happened, but Ragan took it particularly hard.

Matilda said: “He was only three. His mum put him to bed and he never saw her again.

“He was really close to her, they were together all the time, and she was ripped away from him.

“It doesn’t matter what you do for them or what you give them, nothing ever makes up for the loss of a mother.”

She said he would ask where mummy was and say “Daddy’s hands all red” a lot.

“We don’t know if it was something he had heard and was repeating – because there was a lot of talking and gossip – or if it was a memory,” she said.

“He might have seen his dad that night or talked to him, we don’t know.”

Matilda was battling her own feelings of grief while trying to stay strong for her grandchildren and says she just had to “get on with it” for their sake.

She said: “Sometimes we would be out shopping and I’d look at one of the girls and breakdown and start crying. I’d say I had a headache.

“I worried so much, getting in taxis, I was terrified to go out the door in case something was going to happen.

“I kept thinking I was going to wake up, then realising, no, it really did happen.

“They say God doesn’t give you more than you can handle but it does chip away at you.”

Matilda says the kids kept her grounded and gave her a reason to get up in the morning but she was concerned about how they would cope.

She says Ragan continued to struggle with the loss of his mum as a young child and was very withdrawn and had “no confidence at all”.

He needed additional support with work in primary school and did not have friends outside of school.

In high school Ragan was referred to Helm, a charity which helps youngsters gain qualifications and life skills, and started going to the Hot Chocolate Trust, a youth support organisation.

It was then Matilda noticed a change in him. He began to socialise and go out in the evenings to see friends, but he still talked a lot about his mum.

She said: “He would say things to me like his pal has a good relationship with his mum, he wishes he had that and he misses her.”

Ragan used to visit his mum’s grave with Matilda and one day he asked to see where his dad’s grave was.

Jimmy was given a life prison sentence after trial at Edinburgh High Court but just three years into his sentence, in 1999, he was found dead in his cell, having hanged himself.

Matilda said: “I don’t know where he (Ragan) got the idea from, whether it was because of what his dad did – I’ve gone through all the possibilities in my head.

“He never said anything about his mental health. He told me the night before that he felt fed up sometimes, but he seemed alright.

“None of us had any idea he felt like that, it was devastating.”

Matilda says that even though 10 years have passed, there has not been a single day when she has not thought about Ragan.

She still feels pain at the thought of him leaving town on his own and going to the woods alone.

“If I could go back I would encourage him to talk and tell me how he was feeling so that I could support him,” she said.

“He always said he didn’t want to hurt me and that’s why he didn’t speak.

“He used to be in sat in a room with us and go quiet but I didn’t think about it at the time, it’s only looking back that you start to think about those things.

“He was such a beautiful boy, so sensitive and kind. And he was only 18 – it’s not much of a life, all his hopes and dreams gone.”

Matilda said the time passed only reinforces those feelings as she sees Ragan’s brother and sisters grow up and have experiences that he has missed out on.

Her heart still pangs at the thought she will never see Ragan married, have kids of his own or any of the other things he was looking forward to doing.

She lights a candle every year in memory of Ragan and Marilyn on their birthdays and the anniversaries of their deaths.

It is usually a quiet moment of reflection but on the tenth anniversary of Ragan’s death, July 3 this year, Matilda was overwhelmed to see a bus-full of around 20 or Ragan’s friends at her door with flowers.

She said: “I was choked, it was overwhelming. It was so nice to see that they remembered him after all this time and still thought of him.

“He was a beautiful boy and it’s not just me who said that.

“I got two remembrance books when he died with lots of lovely messages in it and I used to think it was just words, but seeing that after ten years, it touched my heart.”

Matilda hopes that in sharing Ragan’s story she can reach out to others who are struggling with mental health issues, encourage them to talk with those around them and seek help.

She said: “If you can’t talk then write it down and give it onto someone you trust and know will help.

“Not everyone can talk, I find it difficult myself, but reaching out in whatever way you can really can help.”

If you need someone to speak to about mental health, depression or suicidal thoughts, there are a number of organisations that can help:

- Samaritans Scotland: 116 123

- Breathing Space: 0800 83 85 87

- Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM, for men only): 0800 58 58 58

- Papyrus (for people aged under 35): 0800 068 41 41

- Childline (for children and young people aged under 19): 0800 1111

- Touched by Suicide Scotland: 01294 274273 or 01294 216895

- Friends Against Murder and Suicide (FAMS): 07736 326062 or 01698 261010