One of Tayside’s most respected scientists has revealed what the future of drug safety could look like for patients.

Professor Roland Wolf, of Dundee University, has spent a lifetime researching how humans respond to drugs, how they’re processed in our bodies and how different drugs react with each other.

For people who take regular medication, or more than one type, Prof Wolf’s work is vital.

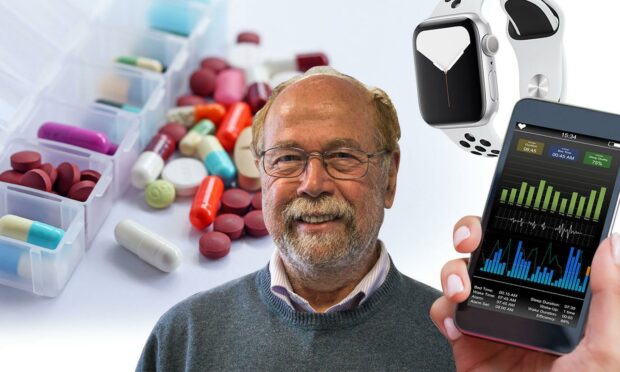

And he believes, with more research, we’re not too far away from having real-time information about how our bodies are reacting to drugs.

This means we will even be able to see it on our phones or smartwatches.

“Drugs are not always one-size-fits-all,” he explains. “But at the moment, for example, a woman weighing 8 stone may get the same drug dose as a man weighing 18 stone.

“Along with my colleagues, I’ve been working to find out why some individuals react badly to certain drugs.

“Our goal is to take research from the lab to the clinical environment and find the right drug at the right dose for the right patient.”

Professor Wolf, who is Chair in Molecular Pharmacology at Dundee’s School of Medicine, says research at Ninewells has a huge focus on that goal.

‘Some taking 10 drugs a day’

“Studies in Dundee have shown, particularly if you’re over 70, you’re taking sometimes more than 10 drugs a day.”

And medication you take for one condition may be eliminated in the body by another medication.

“We’ve identified those human enzymes, the pathways that define how you handle drugs. We look at the beneficial or harmful effects of drugs in the body.

“And understanding that has a major impact on how drugs are developed and used.

Drugs for indigestion or anti-depressants, for example, are handled differently in each person’s body.

Other medication and even genetics can play a part in this.

“For example, there are anti-fungal drugs or drugs for indigestion that inhibit this enzyme system.

“So when you take other drugs with it you get too high levels of drugs. This causes toxicity and can make patients unwell.

“Genetics can also pinpoint individuals who may be highly susceptible to certain drugs – such as anti-depressants.”

A glimpse of the future

Prof Wolf believes in the future patients will be monitored for the drugs they take.

“You’ll have computer-based algorithms to allow doctors to say ‘don’t give that drug but give that one’,” he explains.

“You’ll personalise the treatment of all patients based on that.

“But it is so complicated you still need lab-based studies to develop a database to tell doctors what to do and what not to do.

“Doctors wouldn’t have to understand the basic science, they would get an instruction.”

Fingerprint drug testing first step

A pilot scheme he’s involved in is looking at fingerprint testing for drug levels.

“It’s so we can get drug-based patient monitoring in real-time,” he says.

“The patient would do the test then send it to the hospital to tell the doctor whether levels of drugs they’re taking are sufficient.

“In cancer, for example, is the level of the drug sufficient or too high causing side effects.

‘Covid has shown what is possible’

“It still takes a few years to get these things adopted and demonstrate that it works.

“But once that happens it can be rolled out quite quickly.

“Covid has shown how we can develop ideas and concepts and do research that gets supplied in an incredibly short space of time. Vaccines in a year is immense!”

Precision medicine is the future, says Prof Wolf.

“Both fashionable and important, the whole world is talking about it.

“For example, with cancer, we know the alterations in your genetic code are what drive cancer, so drugs are now targeted to those mutations.

‘Information will go from your phone or watch to your GP’

“Personalised information one day will be a drug monitor on your body, which will take the bloods and tell you what the level of drug is.

“It will go immediately from your smartphone or watch to your hospital or GP.

“We may be some time away from it but there are already guys who are making the sorts of instrumentation that do it.

“I need to get time to talk to the companies that do the same for glucose monitors to get it to do the same for drugs.”

Prof Wolf’s work into drug resistance in cancer patients has had generous funding from the Ninewells Cancer Campaign since he was headhunted to join the University in 1993.

‘An award for the whole city’

He built a team of 20 in the city, funded by Cancer Research UK, and was instrumental in elevating the status of Dundee as a hub of scientific knowledge.

Later receiving an OBE, he was also recently awarded the Sir James Black Medal, a major prize for life sciences researchers, for outstanding work in the safety of the drugs.

“My research wouldn’t have been possible without contribution and support of many others, the ICRF, now Cancer Research UK, and the Dundee community.

“It is an award for the whole city.”