A new book about Thomas Telford explores some of the great Scottish civil engineer’s finest works and offers a fascinating insight into his character. Gayle Ritchie finds out more.

It’s a strange and somewhat surreal sight – an old road disappearing over a crumbling stone-arched bridge into a dark loch.

Flooded and abandoned in the 1950s when hydro schemes raised Loch Loyne and Loch Cluanie in the Highlands, the remains of the structures can still be seen when water levels are low.

Built by Scottish civil engineer Thomas Telford in the early 19th Century, they were part of his Road to the Isles, connecting Fort William to Mallaig. They became submerged under Loch Loyne when the area was submerged with the building of a dam in 1957. And yet, they still exist, like ghosts of the past, prompting questions as to how and when they came to be.

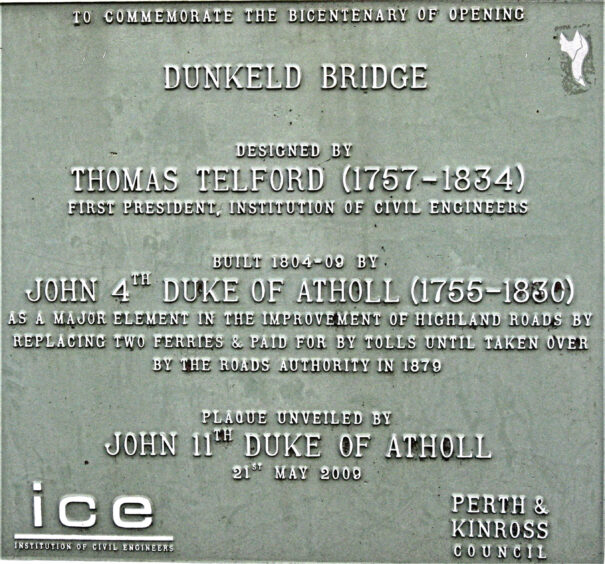

They are just two examples of Telford’s creations and there are many more still standing – including the impressive five-arched bridge in Dunkeld, built between 1805 and 1908, which is considered one of Scotland’s finest.

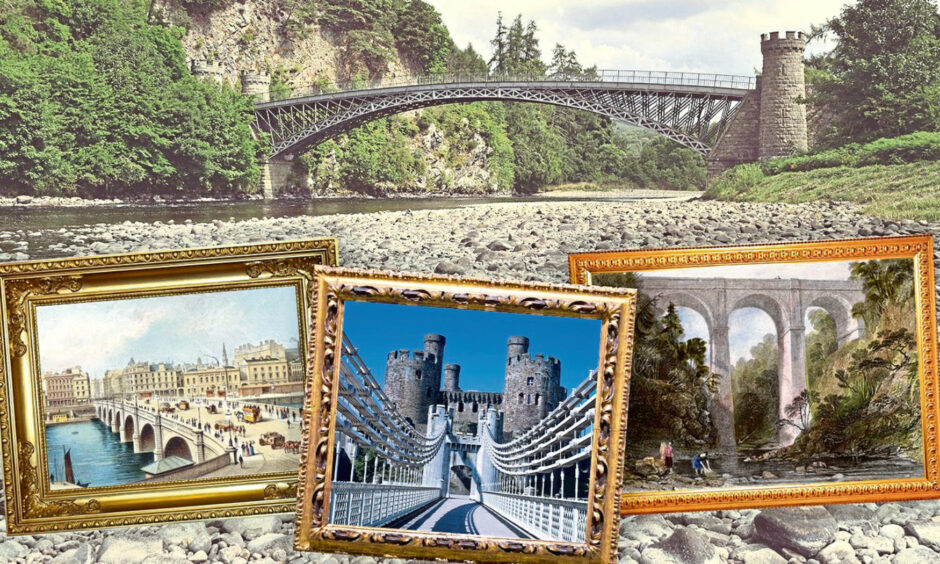

The granite Bridge of Don in Aberdeen, the cast iron arch bridge over the River Spey in Craigellachie in Moray, and the Sligachan Bridge in Skye also feature among his architectural marvels.

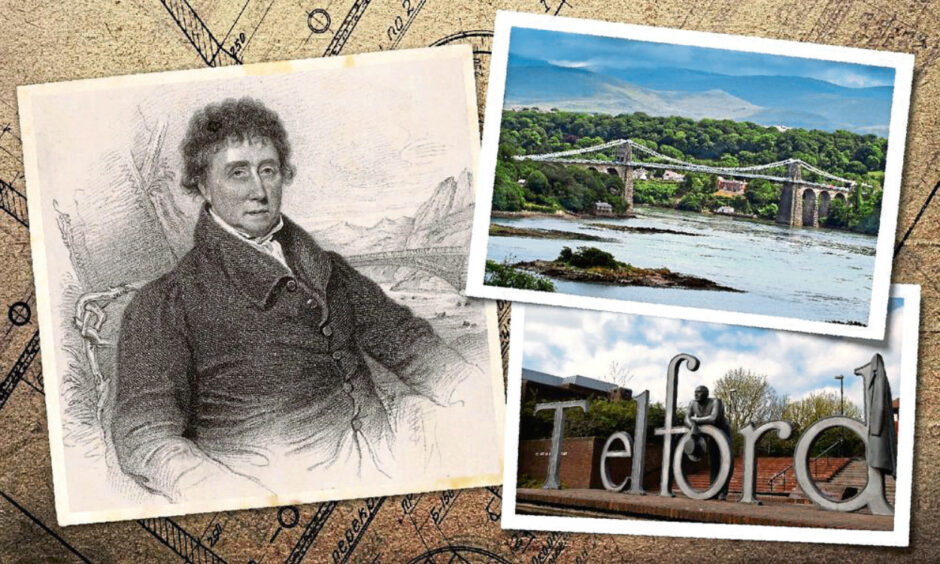

Known as the Colossus of Roads, Telford was a mighty figure in the Industrial Revolution.

He spent two decades in England and Wales designing and building canals, bridges, aqueducts, roads, churches, harbours and jetties.

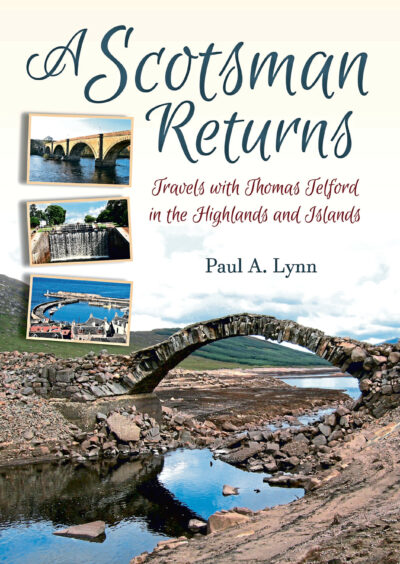

While most of his Scottish work is in the Highlands with the Caledonian Canal being one of his major achievements, a new book by Paul A Lynn revisits the places Telford visited over a period of 20 years, including Dundee, Perthshire, Angus, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire and Moray.

Billed as a “combination of biographical material” and a “modern travelogue”, the book shines a light on Telford the man, rather than the workaholic engineer.

A Scotsman Returns, Travels with Thomas Telford in the Highlands and Islands, reveals Telford, who was so popular and boasted such an infectious sense of sense of humour that he was known as “Laughing Tam”, as a kind, compassionate, rounded character, with a love of poetry and the natural world; a good companion and a generous friend.

In it, Paul, a retired chartered engineer, retraces an extensive Highland tour made by Telford and his friend, the poet laureate, Robert Southey, in 1819. Southey kept a journal of the tour and his written reports on Telford’s bridgemaking, roadmaking and construction of the Caledonian Canal are hugely insightful.

The story of Telford

Born on August 9, 1757 on a sheep farm named Glendinning in Westerkirk, Dumfriesshire, to shepherd John and his wife Janet, Telford is one of the most celebrated civil engineers of all time.

He grew up in poverty, never knowing his father, who died when Telford was only a few months old, leaving his mother almost penniless.

His childhood was spent living with neighbours, who employed his mother when they could, and the two milked and sheared sheep, made hay, and were said to have contrived “not only to live but to be cheerful”.

Mother and son soon moved down the valley to a place called The Crooks, where they were rehoused in a primitive mud-walled thatched cottage.

When Telford was old enough to herd sheep he stayed with a relative, a shepherd like his father, and spent a great deal of time on the hills.

In winter he often lodged with neighbouring farmers, herding cows or running errands and receiving food, stockings and wooden clogs in return.

“Time spent alone among the hills of Eskdale had a profound effect on young Tom, encouraging a deep love of the natural world,” remarks Bristol-based author Paul.

“It is surely no coincidence that as an eminent engineer he would execute many of his greatest works in wild areas of the Scottish Highlands and North Wales – works that show a great sensitivity to landscape and the grandeur of their setting.”

With the help of relatives, Telford was able to attend Westerkirk parish school.

A keen learner, he self-educated for the rest of his days and read up on the latest innovations and advances in science.

His first career was as an apprentice stonemason in the village of Lochmaben, and then at Langholm, a village consisting chiefly of “mud hovels”. Fortunately the landowner, the Duke of Buccleuch, was about to embark on a programme of improvements which opened up a world of opportunities for Telford.

It was there that he began working on paving tracks, bridging fords, building stone houses in place of mud and thatch, and even hewing gravestones and ornamental doorways.

When the Esk runs low in summer, some of his mason’s marks can be seen below the western arch of Langholm Bridge.

Telford went from there to Edinburgh in 1780 as the New Town was being built, but set off for London 18 months later armed with his mallet, chisels and leather apron.

“Like Dick Whittington, but without the cat, he set off for London,” says Paul.

He was introduced to Sir William Chambers, architect of one of London’s most famous neoclassical buildings, Somerset House, where he was employed as a first class mason, keen to demonstrate his skills in fine carving rather than the mere fashioning of solid blocks.

It was here that he began his journey towards becoming one of the most respected civil engineers of his time.

In his spare time, he immersed himself in the mysteries of chemistry, and wrote to his friend Andrew Little in Langholm that he was “chemistry mad”, and that the pocket book he always carried was crammed with “facts relation to mechanics, hydrostatics, pneumatics, and all manner of stuff”.

He enjoyed the theatre and fell for a famous actress known as Mrs Jordan. Sadly she was “spoken for”, by among others William IV with whom she had 10 children.

Man of the world

He attended concerts and became a “man of the world”, powdering his hair daily and putting on a clean shirt three times a week.

He still found time to write letters home to his mother, using block capitals so she could decipher them by her cottage fireside.

He also wrote poetry and one of his works, a poem about his home village of Eskdale, was published.

This passion for verse brought him into contact with the reigning poet laureate Robert Southey. The two men met for the first time in Edinburgh in 1819 and decided to head off on a journey across Scotland.

Telford was 62 by this time and involved in many Highland infrastructure projects, including the revered Caledonian Canal.

During their six-week journey, they often had to share a room which might have proved challenging for many people.

However, the two got on like a house on fire. Indeed, Paul tells a story of how Southey was bothered by a “volcano” on his head, a grim, pustulating tumour which had to be cleaned and dressed… and Telford had no issue in playing nurse.

In Southey’s journal of the tour, his first impressions of Telford states: “There is so much intelligence in his countenance, so much frankness, kindness and hilarity about him, flowing from the never-failing well-spring of a happy nature, that I was upon cordial terms with him in five minutes.”

In a horse-drawn landau and accompanied by another family, the men’s route took them to Stirling and the Trossachs, Perth, Dundee, Montrose to Aberdeen, then west to Banff, Elgin and Grantown-on-Spey.

They then travelled along the Moray coast to Forres, Nairn and Inverness before heading to Dingwall, Bonar Bridge and Dornoch and down the Great Glen to Fort William, Glencoe and Inverary, finishing in Glasgow.

Along the way they visited many of Telford’s constructions.

Parting after six weeks, Southey lamented: “A man more heartily to be liked, more worthy to be esteemed and admired, I have never fallen in with.”

Indeed it was the loyal Southey who came up with the nickname Colossus of Roads for Telford – having made improvements to more than 1,000 miles of roads, many in the Highlands. He died in 1834, aged 77, in London.

Delving deep

Paul was inspired to write his new book, his 16th, after having delved deep into Telford’s story.

“Since I retired I became more interested in the industrial revolution and the engineers, particularly civil engineers, that made it possible,” he explains.

“I wrote two books about Scottish lighthouse engineers a few years back. I knew Telford’s name but didn’t know much about him. I was attracted by the fact that he built a fantastic aqueduct in north Wales (Pontcysyllte aqueduct).

“I felt there wasn’t a book which brought out his personality, his fascinating character. I wanted to write a book that included these details, as well as to include information about the canal and aqueduct in north Wales.

“When I was researching that book, about four years ago, I realised Telford had done a great deal of work in Scotland that I didn’t know about.

“I wanted to make more people aware of him – of the man himself – and present Telford as a man of the Scottish Enlightenment, whose engineering had profound social consequences.

“His harbour works were crucial to the fishing industry, for example, and his bridge designs were a blend of art and science.”

There is a town in Shropshire named after Telford, but Paul says most people in England know him “for the Menai suspension bridge in Wales,” and that almost nobody realises he was born in Scotland, and often went back there to try to “sort out” the Scottish infrastructure.

While many perceived Telford as an obsessed workaholic, Paul, during his research, discovered that he was in fact “a very sociable man”.

“He’s widely regarded as having a rather one-track mind and work-obsessed but that’s not really fair on him,” he says.

“He’s got a much wider, more generous and attractive personality than he’s generally been credited for and I’ve tried to bring that out in the book. I’ve delved deeper and come to a different conclusion about him.”

Paul has had a lifelong love of the Scottish Highlands and Islands, visiting to hike and explore since he was a young lad, and in fact he met his wife in Mallaig 50 years ago.

“We were waiting for the ferry to take us to Skye,” he recalls. “I was on holiday with a school friend. She was on holiday with a work colleague.

“It had been pouring with rain for about four days and my friend and I had to abandon our idea of trekking over the hills from Glenfinnan to Mallaig.

“Instead we took the train to Mallaig and went into a rather scruffy little cafe on the pier head. I met my wife there! This was 50 years ago now. What’s more she came from Germany! And there’s an anecdote in the book about that!”

- A Scotsman Returns: Travels with Thomas Telford in the Highlands and Islands is available direct through publishers Whittles of Dunbeath, Caithness. whittlespublishing.com