A model of the Titanic will finally be constructed to recognise the gallantry of a Mearns man who steamed to the rescue of the doomed liner.

Allan Hay of Gourdon purchased weekly booklets and pieces of kit in the 1970s, at a cost of more than £600 in today’s money but he never realised his dream of building the model.

Mr Hay recently approached Dave Ramsay of Mearns Heritage Services with a proposal to donate the model kit of the Titanic to see if it could finally be constructed.

Mr Ramsay was aware, through his Rotary Stonehaven connections, a plan was afoot to create a Stonehaven Men’s Shed and he considered it the perfect opportunity.

The Men’s Shed now plans to construct the model and gift it back to the Maggie Law Maritime Museum in recognition of the bravery of Gourdon man John (Sarge) Cargill.

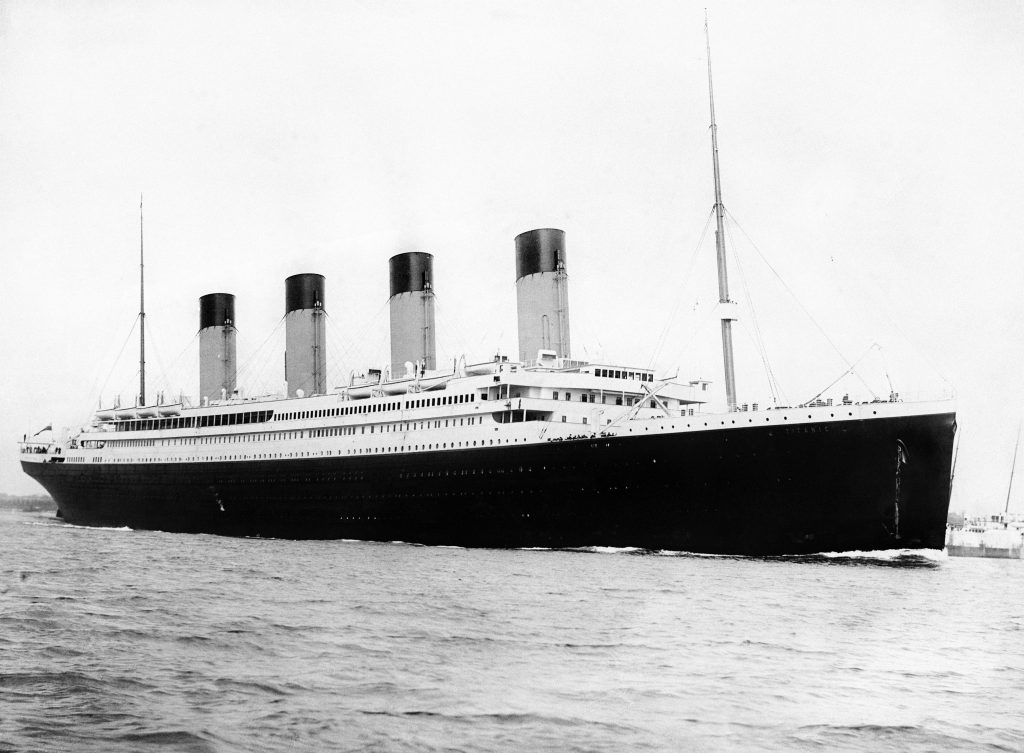

Mr Cargill was an 18-year-old quartermaster on the Carpathia, which raced to the scene when the Titanic struck an iceberg in 1912. More than 700 passengers were pulled from the icy waters of the North Atlantic.

Mr Cargill scooped up babies in coal sacks from the lifeboats of the Titanic and was awarded a bronze Titanic medal for his part in the rescue.

Many survivors beat a path to his door in later life to thank him.

Mr Ramsay said: “This was the perfect opportunity to bring together a number of social, community and heritage agendas.

“The Men’s Shed could construct Allan’s model, providing focus and occupation for members but with a future focus of gifting it back to the Maggie Law Maritime Museum in Gourdon, as a donation of a lasting piece of maritime heritage and a recognition of the bravery of a local man.”

Chairman of the Men’s Shed Bill Allan, said: “This is an excellent project for the Men’s Shed, and fits in well with our objectives of helping support the local community in general, and in this case the Maggie Law Maritime Museum in particular.”

The Carpathia was the first vessel on the scene after the Titanic struck an iceberg and sank on her maiden voyage, with the loss of over 1,500 lives.

The ship picked up an SOS just before midnight and altered course to help.

It took four hours to reach the scene, south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

Mr Cargill later said: “At first we did not know it was the Titanic, but then the wireless room worked out that it had to be her distress signals.

“In those days, it was all dot and dash radio signals. There was an SOS at the beginning of the message.”

Mr Cargill could not believe the Titanic was in trouble because it was considered to be ‘unsinkable’.

The crew never saw the Titanic because she sank before they got there. Mr Cargill did see the iceberg, which he said “was a terrible size”.

The bronze Titanic medal was presented to Mr Cargill by “the unsinkable” Molly Brown, a first-class passenger rescued by the Carpathia.

He later served in both world wars with The Black Watch and Royal Navy before returning to Gourdon.

In that time he gained a Military Medal and several fighting honours as well as a gallantry card, all of which were kept in a “Christmas box” by his family.

Mr Cargill died in 1980 aged 87, two years after his wife Mary.

The curious case of Robert Douglas Spedden

It would be more than 70 years before the wreck of the Titanic was found, split in two at the bottom of the sea.

It was just after 9.30am on April 10 1912 when passengers began to arrive at Southampton before the start of her maiden voyage to New York.

It was at 11.40pm on April 14 1912 that Frederick Fleet, a lookout, spotted an iceberg ahead and warned the bridge immediately.

The First Officer, William Murdoch, ordered Titanic to be steered around the iceberg, and for the engines to be put into reverse.

It was already, however, too late to avoid it, and the ship’s starboard side collided with the ice.

Below the waterline, a series of holes were made and watertight compartments were being flooded at an alarming rate.

Titanic began to sink bow-first, but she only had lifeboats for half the people, and the women-and-children-first rules led to more men losing their lives.

Just over 700 people lived to tell the tale, with the Carpathia taking them to New York — 1,500 had died.

Robert Douglas Spedden, a six-year-old New York boy who was on the Titanic, was one of the lucky ones to be saved by the Carpathia.

Tragically, in a twist of fate, three years later he was hit by a car and killed.

He was one of the first people ever to die in a collision with such a vehicle.