A Tayside scientist who played a key role in organising pioneering Discovery expedition to the Antarctic will be remembered in his home town ahead of the mission’s 120th anniversary next year.

George Robert Milne Murray was born in Arbroath in 1858 and educated at the town’s High School before studying botany at Strasbourg University.

Returning to the UK in 1876, he was employed at the Botanical Department of the British Museum, later becoming Keeper of the Botanical Department of the British Museum in 1895.

His growing reputation in the scientific community saw him elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1897.

He married Helen Welsh from Brechin in 1884 and the couple had a son and daughter.

Murray’s obituary, published by the Royal Society, outlines his many achievements and appointments, including lecturing on botany at St George’s Hospital medical school and the Royal Veterinary College.

He also published some 40 scientific papers and is associated with a number of expeditions, including the 1886 solar eclipse expedition to the West Indies.

However, it is his work with the British National Antarctic Expedition, which set sail in 1901 that is best known.

Murray was appointed as Scientific Director on the project and edited The Antarctic Manual for use on the expedition, contributing a short chapter to it.

In 2010, a first edition of the manual sold at auction for £2,500.

As part of the preparations, Murray was kept extremely busy with the provision of stores and apparatus and sailed as far as Cape Town with the expedition, which is as far as far as his London duties would allow him to travel.

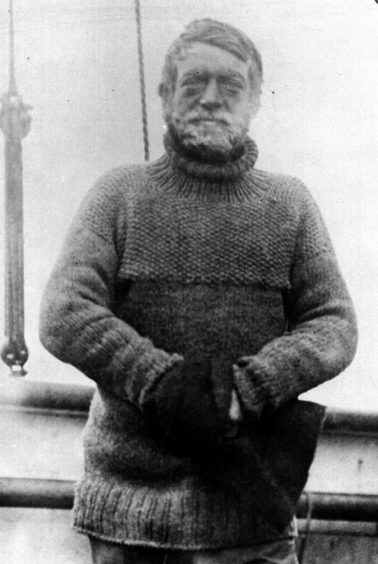

The ship’s complement included men who would become household names, such as Captain Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton.

Murray’s wife Helen died in 1901, and after battling ill-health for some years, Murray retired in 1905.

He died of cancer in 1911 and was survived by his two children and his second wife.

He did not live to hear the news that his former colleague, Captain Scott and his team had met with disaster on the later, ill-fated Terra Nova expedition to the Antarctic.

A mountain in the Antarctic, now bears his name in honour of his work, and the fungal species Schizophyllum murrayi was also named after him.

Angus Council leader, Arbroath West and Letham Independent councillor, David Fairweather, said Murray’s achievements should be recognised in his home town and further afield.

He said: “The amazing contribution to science by George Murray should be highlighted and celebrated.

“Too often we forget the achievements of local people who have gone on to do great things, and the fact that Mr Murray has not only had a mountain named after him, but a type of fungi as well, is very much a case in point when he is largely unknown in his home town.

“With the 120th anniversary of the Discovery expedition just months away, I think it would be incredibly fitting that we look at how best we can celebrate and commemorate Mr Murray, especially as the Discovery continues to attract so many visitors in Dundee.”

The Expedition

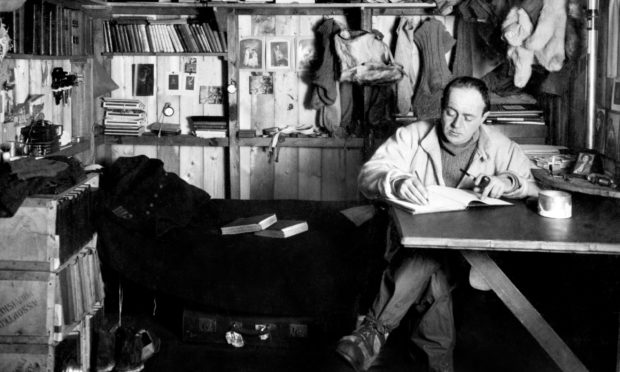

The British National Antarctic Expedition to the Antarctic lasted from 1901 to 1904 and was an iconic part of the ‘heroic age of polar exploration’.

It is better known as the Discovery expedition after the Dundee-built ship specially constructed at great expense to transport the team. Its design was based on the mighty whaling ships for which the city was famed.

The expedition consisted of a number of projects, both exploratory and scientific, including ‘meteorological, oceanographic, geological, biological and physical investigations and researches’.

The sea journey alone took five months, after which, the expedition began in earnest.

Although the crew had taken a pack of sled dogs with them, but the dog food had gone off on the journey and the dogs became increasingly lame – dying one by one.

The harsh environment also took its toll on the men who began to show signs of scurvy, frostbite and in at least one case, snow blindness.

Ultimately, the key players in the expedition, Robert Falcon Scott, Dr Edward Wilson and Ernest Shackleton covered 950 miles on foot over 93 days.

They had travelled further south than anyone before them, returning to reach the Discovery, against all the odds, in February 1903, making landfall in the UK in September 1904.

The scientific discoveries from the expedition would ultimately fill ten substantial volumes, with more than 500 species discovered and extensive maps of the area made.

Scott and his colleagues would be hailed as heroes and Scott in particular would receive a number of honours.

The expedition was seen overall as a success, but in time it would be overshadowed by the next Antarctic adventure which reached the South Pole and secured the explorers names in history, but from which there would be no return.

Scott and four comrades, including Wilson, died on the journey back from the Pole, to which they had been beaten by a Norwegian expedition more than a month earlier.