Michael Alexander meets volunteers who are in the final stages of building a replica First World War aircraft which honours the historic role of a Montrose flying ace.

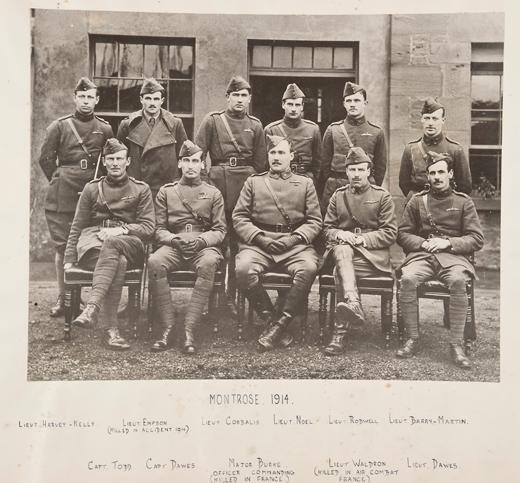

The First World War was a little over a week old, and the design of aircraft was barely out of aeronautical nappies when, on August 13, 1914, Major Charles Burke, the commanding officer of Montrose-based No 2 Squadron, led the Royal Flying Corps to France.

The flight from Dover across the English Channel was largely uneventful.

But Major Burke was none too pleased when he realised that one of his junior officers had landed before him.

Lieutenant H.D. Harvey-Kelly had flown directly overland to Amiens rather than follow the coastal route taken by the rest of the squadron.

“As I was approaching Amiens I saw an aircraft already on the ground. It was Harvey-Kelly, “Major Burke later wrote in his diary.

Becoming famous as the first British pilot to land in France was worth the dressing down received by Harvey-Kelly, who had a reputation for high spirits.

Now, more than 100 years later, Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre is putting the finishing touches to a major commemoration of this aviation milestone as part of its £100,000 ‘First in France 1914’ project.

With support from the Heritage Lottery Fund a new building has been erected to house their First World War artefacts, photographs and aircraft.

For the past 18 months volunteers have also been building a full size replica of the B.E.2a aircraft that was flown by Lieutenant Harvey-Kelly.

And with the replica aircraft nearing completion, it will be officially unveiled at a ceremony on August 12, to be attended by dignitaries including current members of the RAF Lossiemouth-based No 2 Squadron, and descendants of those who served at Montrose in the First World War.

The story of Harvey-Kelly, and Burke, who both died later in the war, will also feature on BBC Countryfile on Sunday June 5.

Montrose Air Station curator Dan Paton, 75, came up with the idea of building a replica B.E.2a in 2013.

“There’s controversy about whether Harvey-Kelly was the first pilot to land in France – some say it was a Captain Waldron – but we have got Major Burke’s diary which is a unique historical source and definitive proof,“ he explains giving The Courier a tour of the aircraft under construction in the Montrose hangar.

“What happened of course was that No 2 Squadron left Montrose for Dover on August 3 1914, the day before the outbreak of war.

“They joined up with the other squadrons No 3, 4 and 5. No 2 was the most experienced so it led.

“They had to wait until August 13 to get good weather. And then they all flew.”

By 1914 B.E.2a’s were the first practical British aircraft design and by that time No 2 Squadron was fully equipped with them.

It was designed by British aircraft design pioneer Captain Sir Geoffrey de Havilland.

In the early days, the British military were trying to work out what role aircraft could play in war. Some seasoned army sceptics rubbished the role of aircraft at all.

But Major Burke, a distinguished soldier in his own right, visualised aircraft as having the potential to be the equivalent of a “mobile hill”. If you command the high ground you command everything, was his view. And so it proved as they played a key reconnaissance role over the trenches. Remarkably, No 2 Squadron, which now flies Typhoon jets from Lossiemouth, is still known as No.2 Army Co-operation Squadron.

Alan Doe, 80, is chairman of Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre. The retired aeronautical engineer, who was engineering director at Westland, used his experience of working on helicopters and inflight refuelling equipment, to lead the design and construction of the B.E.2a replica using the original 1913 plans kept at the National Archives.

Not only has he been leading the volunteer team of Jules Stevenson, Andy Lawrence, Brian Crozier and Brian Thorby – he has also been playing a hands-on role.

“I’m accustomed to building aircraft, but what I wasn’t accustomed to was building with these materials, “Alan explains, describing the replica as “just like a big model” which could not fly.

“We used Douglas Fir and Ash for the fuselage. And for the wings we used calico, held together by wires.”

With a limited budget and limited timeframe, the team used local firms and for airfoil was assisted by the carpenters shop at RAF Leuchars before it closed.

“People think these old aircraft were rickety and that people didn’t know anything, “ he adds. “That’s not actually true. It’s amazing how much knowledge had been accrued in the 10 years since the Wright Brothers first flew.

“The one thing that people had not yet managed to sort out though was how to recover from a spin.

“Aircraft designers didn’t establish how to recover from that until 1916. It was a perilous existence in that respect. But designers knew about fundamental aerodynamics, and this paved the way for later aircraft design. It’s been a fascinating journey.”

malexander@thecourier.co.uk