Michael Alexander speaks to fifth generation Angus farmer Grant Baird who recently came out as a “closet poet” – and who has just had his works published by a sister he never knew existed in America.

As a fifth generation Angus farmer, Grant Baird has always been well versed on the twists and turns of his family tree.

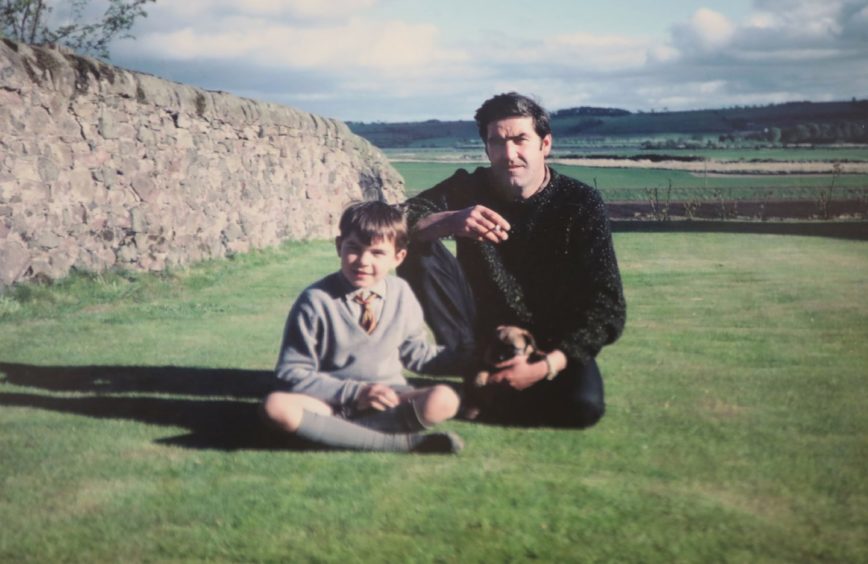

With 19th century farming roots in Ayrshire, his family, who came to Angus via Dundee, have been farm tenants at Mains of Dun near Montrose since 1921, and Grant himself took over the farm aged just 16 in the late 1970s after his father was killed in a car crash.

But it was quite a shock when in late 2019, Grant was contacted out of the blue by a woman in America who, it turns out, is the half-sister he never knew existed.

“I was approached in 2019 through Ancestry.com,” recalls Grant, 60.

“I’m a member and have my own family tree listed there dating back to 19 oatcake.

“I got a message saying if my name is George Grant Baird, this person might be interested in getting in touch. They might be a relative.

“Anyway, it turns out this woman is my half-sister that I knew nothing about. She’s a year older than me and was my dad’s child by another woman who he had been seeing before he married my mum.

“It was an amazing experience. You’ll have seen the telly programmes. Well, this was exactly the same except there wasn’t Davina McCall involved!”

Adopted

Grant learned that his half-sister Jane was adopted when she was a fortnight old.

Brought up in Dundee, she was educated in Dundee and Edinburgh before emigrating to the USA in the early 1980s.

A mother, gardener, poet, footballer, retired English teacher and editor for Microsoft, she ended up in Seattle where she now lives with her wife, who owns and operates a print works.

Researching her family history, Jane had discovered that her birth mother had died in her mid-40s.

She now learned that, coincidentally, her birth father had also died at a similar age, aged 41, in a car accident.

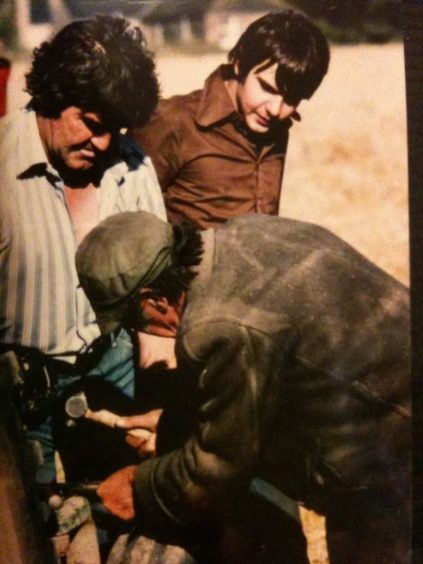

However, Grant was able to show her a picture of his dad arm in arm with her birth mother at a wedding in Aberdeenshire when he was an usher and she was a bridesmaid.

Grant presumed they had “obviously had a fling”.

But when he tracked down some still living other bridesmaids, they told him: “No, no no – they dated for a while!”

Relationship building

Grant says the most frustrating aspect of discovering his ‘new’ sister is that because of Covid-19, they’ve not been able to meet yet in person.

Inspired by her existence, they’ve Face Timed each other across the Atlantic.

Grant laughs that relationships are hard enough at the best of times, becoming even more awkward when trying to create some kind of relationship using only social media. “At the moment our relationship is pure as the driven snow,” he laughs.

However, the initial contact has already led to another quirk of fate.

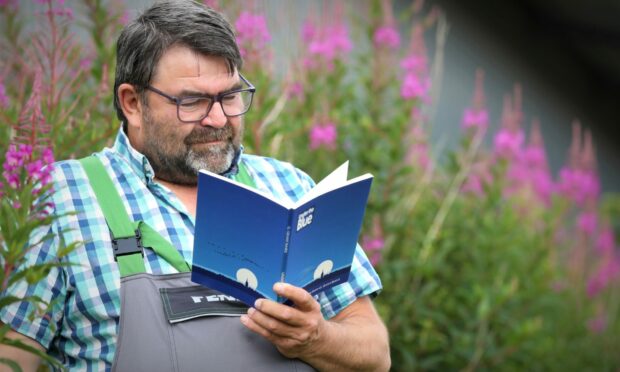

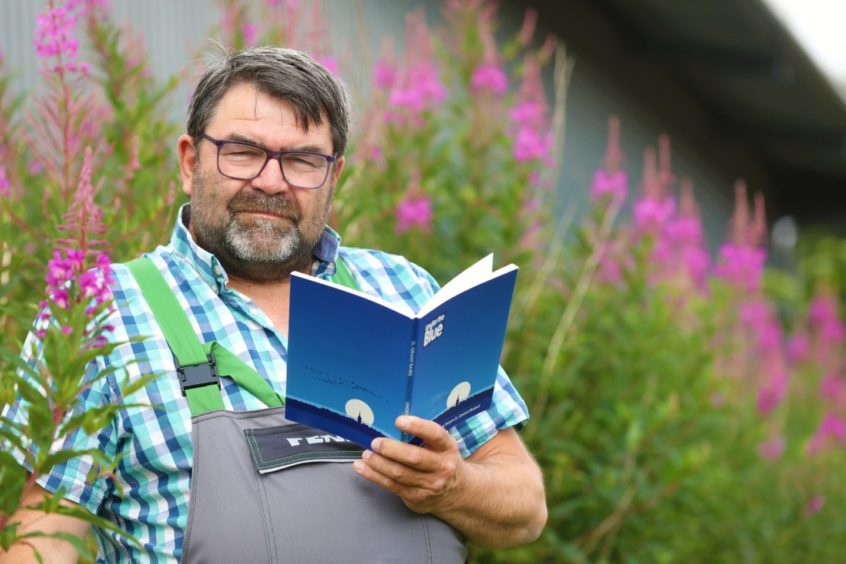

Having written poetry all his life and only relatively recently self-publishing some of his work, Grant’s new big sister thanked him by arranging to have his poetry professionally published in Seattle as a special 60th birthday gift.

“I had wanted to share my poetry with Jane who it turns out had been an English teacher,” says Grant.

“After I shared some of my poetry with her she said ‘you know what I’m going to do for your 60th birthday I’m going to publish some of your poetry’.

“As soon as the chance came all this poetry came out of nowhere and I wrote another 35-40 poems over a year.

“They’ve just started another print run of the book and are going to send more over.”

Father’s sudden death

Born at Arbroath Infirmary and raised at Mains of Dun where he’s stayed all his life, Grant, who has a younger sister, was educated at Montrose, at Lathallan and then Strathallan – before leaving school when his dad died.

He went to college in Aberdeen for a year to study farming.

Perhaps not surprisingly, his father’s sudden death has influenced some of his poetry over the years.

“He was driving home and left the road, hit and tree and that was it,” reflects Grant.

“It’s history. I had to leave school and try to run the farm. It was down to me and my mum to sort it out and try and pick up the pieces.”

Although Grant’s dreams didn’t involve tractors as a youngster, he remains philosophical about the challenges that emerge in life.

Away from the farm, he played rugby from a young age then moved into amateur operatics – singing up and down the east coast with Montrose Opera then Aberdeen Opera.

Memorable shows over the years include Chess and Jesus Christ Superstar where he played the baddie, Judas.

It was only quite recently, however, even after his initial contact with America, that he gave his poetry a first public airing.

Overcoming embarrassment

He spoke to Aberdeen-based friend Sonja Rasmussen – a Press & Journal journalist and creative writing expert he’d known through operatic circles – about his poetry.

Although he’s been writing all his life, he never had an outlet for it, and was always a “bit embarrassed” by it because “how do you know if it’s any good?”

“It was actually Sonja that I spoke to first,” he says. “You get to 60, and I thought to myself, what am I going to do? I can’t let this rest, I’ve got to let somebody see it and tell me if it’s any good.

“So I texted Sonja some of it – she was in some of the opera things years and years ago. She said ‘wow, ok…’. She was kind enough to look at my work.”

Asked to describe his creations, Grant says it covers everything from the natural world round about him to personal issues and his father dying. “It’s just about life and death and love and lives,” he adds.

He also sometimes finds inspiration on the farm.

“It’s strange,” he says. “The inspiration comes from daily living.

“People say things or you come across things and it sparks something in your head and you go ‘oh my god I need to write that down’, or you come home at night and try to form an idea or write a poem out of it. I write songs and play music as well.

“But it’s funny I don’t do both at the same time – I either do one or the other.”

Living life

Grant is a firm believer that to write poetry you have to “go and live life”. It’s something that has to come from within rather being learned.

Only later did he start reading about poets he ended up liking such as Liverpudlian Roger McGough and Scots like Norman MacCaig.

There was another quirk of fate, however, when he discovered that poet Violet Jacob who wrote poetry, mostly in the lowland Scots dialect, during her 4+ years in India, is buried in the local churchyard at Dun.

“I’d always kind of kent about her – she was part of the local aristocracy here,” he says.

“My own family rented the farm that’s on the estate.

“I knew she had been born at House of Dun and I knew her to be a writer – I owned a copy of her 1931 family history, The Lairds of Dun, but that was about it.

“At the end of 2020, while scouting out relatives’ graves in Dun kirkyard, I was shocked to come across Violet and her husband’s grave in the quietest corner quite by accident. I thought she was in Kirriemuir! It prompted a bit of research.”

As a boarding school educated boy, Grant makes no claim to being a Scots speaker.

However as a lad, he can remember the shock of listening to his dad suddenly speak a different language while yokin’ the men in the morning, and the intense often rowdy banter between them all.

To discover that Violet was one of Scotland’s pre-eminent poets in the Scots vernacular was a revelation.

What next?

Looking to the future, Grant laughs he’ll never get rich writing poetry and that farmers never retire – although with three sons and a daughter, two of his sons are now doing more of the work on the farm.

His youngest son Wallace plays football for Dundee FC 07s youth team. He loves running him up and down the road to watch him play.

One day he also hopes to meet his ‘new’ sister face to face.

But in the meantime, his partner Dawn Wallace, who runs The Barbers Shop at 43 Market Street, Montrose, will be selling the poetry books there with proceeds going to rugby legend Doddie Weir’s MND charity, My Name’5 Doddie Foundation.

“I’m always in awe how things work out,” smiles Grant.

“All through my life I’ve always had opportunities to do things as you do, but not always to take them up.

“With the poetry book I thought, ‘Christ, I’ve got to take this one’ and went for it. I’m really pleased with how it’s worked out.”